The indigenous peoples have been living symbiotically with the environment in Taiwan for thousands of years. For generations, our ancestors have learned how to co-exist with nature by battling for life amidst forests and have developed rules and taboos for indigenous peoples in respective areas; the Bunun call it samu, the Atayal call it gaga, the Truku and Seediq call it gaya or waya. The unspoken rules may not exist as written records, but they are passed down through generations and can be found in the oral culture of the indigenous peoples.

Who's Civilization?

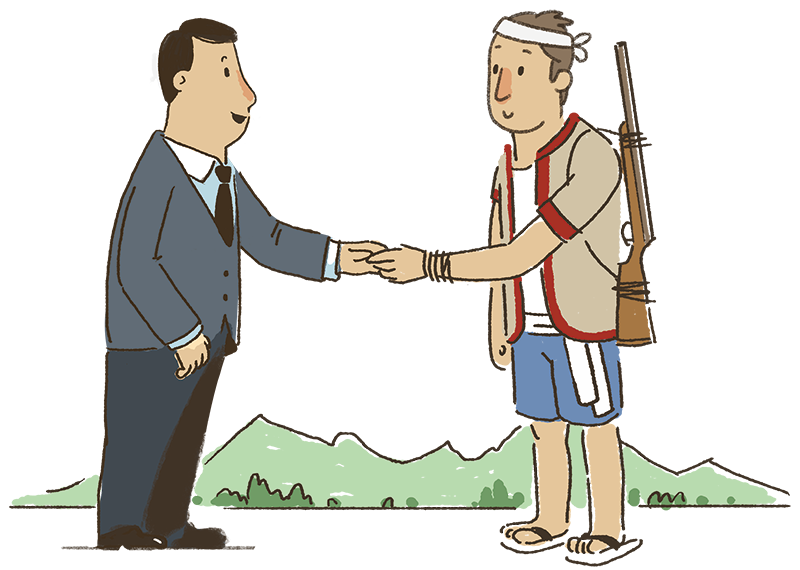

After the Colonists Arrived

Hunting is sacred to the indigenous peoples. Elders taught our people to not hunt exceedingly, and that if we shoot a prey, however far it is, we must chase it down and not let the prey perish in waste; when killing the prey, we must always be grateful and pray for it, thank the life that provide us sustenance. Our people must abide by the codes rigorously, avoid violating taboos while maintain balance in the ecology.

But when foreign colonizers began coming to Taiwan in the 16th century, they attempted to “teach” the indigenous peoples ways of the civilized life. The Japanese people introduced a set of rules they call civilization, confining the original lifestyle and religion of the indigenous peoples to secure their obedience. For example, afraid of armed rebellion from the indigenous peoples, the rules controlled the hunting firearms the indigenous peoples relied on for livelihood and banned the training in men's assembly room; gradually dismantling the traditional social organization of the indigenous peoples with group relocation policies. Furthermore, the Japanization policy was implemented to turn the indigenous peoples into “modern and civilized” subjects of the emperor.

Later, the government of the Republic of China continued such logic of civilization and following the trend of international ecological conservation in the 1980s, national parks were delineated, and the Wildlife Conservation Act and the Forestry Act were enacted. The indigenous peoples living within the boundaries of national parks were evicted, due to the enactment, from the traditional territories they have resided in for generations, and the original lifestyles of hunting and gathering became known as “crimes” according to the laws of the Republic of China.

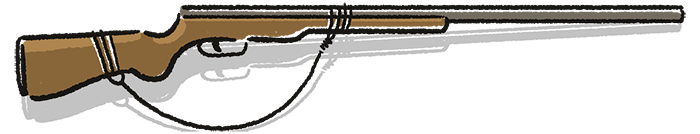

In 1983, in the name of protecting social order and guaranteeing the safety of people's life and property, the government issued the Controlling Guns, Ammunition and Knives Act, and began controlling knives and firearms. The shotguns used by the indigenous peoples for hunting may be listed as exceptions to the Act, but details of the articles confine the shotguns to low specifications and DIY guns only, leaving hunters with the only choice of unsafe shotguns. Accidental discharge and bore burst occur almost every winter during the peak hunting season, causing serious injury and even death to indigenous hunters. According to the statistics of the National Police Agency of the Ministry of the Interior, there have been 33 casualties due to shotgun misfires, 11 of which died. For instance, in 2016, the Bunun pangolin conservationist Hai sul died because of an accidental discharge from his DIY shotgun. Not taking the indigenous culture and traditional lifestyle into consideration when enacting regulations is no doubt putting the lives of indigenous hunters at grave risk.

Shotgun Specification Restrictions

In 2009, Paiwan hunters used DIY breech-loading shotgun (Hilti shotgun) to hunt, and was charged with violation of the Controlling Guns, Ammunition and Knives Act. In the 2013 retrial, the supreme court ruled him not guilty, and deemed his shotgun a necessary tool of livelihood that should not be twisted as a tool of crime simply because the Act was wrong. Such verdict forced the National Police Agency to reinterpret the restrictions on shotgun specifications. Breech-loading is now allowed as well as muzzle-loading but still limited to DIY shotgun.

Stigma of Uncivilization

Why has the Teachings of our Ancestors become Crimes?

In the media, we often see terms such as indigenous people “poaching” wildlife and “illegally” gathering wild plants, causing the audience to wonder why is it that the indigenous peoples just have to “break the law”? They even ask questions including, “why don't the indigenous peoples buy their meat from the supermarket if they want it, why hunt the wildlife? Isn't that just cruel?” “Uncivilized”, “taking lives” and “destroying the ecology” became the stigma of the indigenous hunting culture.

The indigenous hunting culture is more than just the need for protein. For example, in the Bunun culture, there is no word for "hunter" because hunting is not just a profession, but the responsibility every Bunun man must bear. The hunting culture is not just about the skills, but the knowledge of the forest and the nurturing of character as a fellow indigenous people. While hunters hunt in the mountains, they are observing the changes to their traditional territory, guarding and patrolling their land; many rituals and ceremonies ensued in correspondence to the hunting culture.

However, with the massive decrease of the wildlife population in Taiwan, the public intuitively point fingers at hunting as the main reason behind the wildlife conservation crisis, and completely overlooking the fact that the fundamental reason lies in destroyed habitats due to development. Ecological conservation and the continuation of indigenous cultures should never have been opposing terms, but the lack of appropriate government regulations coupled with exaggerated mass media exposure have intensified the public misconception, and the harm is done not only unto the hunters but the overall heritage of indigenous cultures.

Is Hunting Wrong?

Late 2015, Bunun hunter Talum Suqluman used his shotgun to hunt a muntjac and a Formosan serow for his mother and was sentenced to 3 years and 6 months in jail. Such verdict sparked heated public debate and rescue work began. The prosecutor general filed an extraordinary appeal on his behalf, the case became the first case ever to be live streamed at the supreme court, and the first time the supreme court filed for constitutional interpretation. The case is currently on appeal.

Who's Mountain and Forest?

Guardians of the Mountain and Forest Treated like Thieves

After the “state” came to Taiwan, everything on this land belonged to the state. The indigenous peoples gather not only ingredients for food, but materials for building houses and making daily wares, yet somehow such everyday chore became "violations" to the state.

In 2005, the Indigenous Peoples Basic Law was adopted, stating that the indigenous peoples have the right to use natural resources according to cultural customs. But in the same year, the Qalang Smangus community in Jianshi Township, Hsinchu County, was accused of theft by the Forestry Bureau for bringing beech back to the village for public use, beech that fell because of typhoon. They were found guilty in the first instance, and again guilty in the second instance but with a reduced sentence. The Atayal people insisted that there were no violations by gathering forest products within the traditional territory of the Atayal people according to their ways of life and continued to appeal the case. They were finally acquitted in 2010, when the supreme court sent the case back to the high court for retrial. The litigation lasted 5 years.

However, in recent years, there are still incidents of indigenous people charged with theft for gathering wild jelly-fig and rattan in the mountains. Even though we can cite the Indigenous Peoples Basic Law during the judicial process to protect the indigenous right to use natural resources, without amendments to relevant regulations, officers on the front-line have no choice but to transfer such case “according to the law”, and the prosecutor must prosecute such case “according to the law”. The frequent visits to the court and the lengthy judicial process are all exhausting for the indigenous peoples. “Were we really wrong? Why else would the prosecutor do this to us?” The heartbreaking responses of the Bunun people showed, again and again, the conflict between the current rule of law and the culture of the indigenous peoples.

The main reason our ways of life are questioned lies in the fact that the land we live on is no longer co-owned by the communities. The delineation of national parks drove the indigenous peoples out of our traditional territories, applications for hunting within traditional territories were denied, and people were forced away from the land and life they were accustomed to, which also gave rise to protests.

In 2015, Bunun pastor Kavas, who participated in pulling down the bronze statue of Wu Feng, brought the youth of the Litu community back to the Sancha Mountain located inside the boundary of Yushan National Park. There he declared it their traditional territory and sowed millet seeds to demonstrate their determination to defend their land but was subpoenaed for investigation by the Guanshan precinct in Taitung county for “violation of the National Security Act”.

In 2016, the “Skaru Watershed Collective Community Sovereignty Alliance” formed by the 12 Atayal communities in the Skaru watershed gathered in Guanwu National Forest Recreation Area. They protested the prolonged restriction by the Shei-Pa National Park Headquarters, which did not allow the Atayal people hunting and gathering in their traditional territory and demanded that the Forestry Bureau and the Shei-Pa National Park restore their right to use the traditional territory.

Once the proud guardian of the mountains and forests, accused of theft in the hundred of years since the colonizers arrived. The prolonged institutional oppression and stigmatization have made life extremely difficult for the indigenous peoples, forcing them to take to the streets in protest, or exhaust and expire in between the numerous individual cases to rescue.

The Dawn of Change

Make Future Better by Learning from the Indigenous Peoples

Legislative adjustments and amendments to inappropriate regulatory restrictions cannot be completed overnight, and indigenous political participation is still confined in many ways, even with the 6 seats of indigenous legislators guaranteed by the Constitution, they are still the minority in the Legislative Yuan. Regulation proposals relevant to indigenous rights are always put on hold amongst the many prioritized bills, 14 years after the Indigenous Peoples Basic Law have been adopted, relevant regulations and amendments to conflicting laws are slow, to say the least.

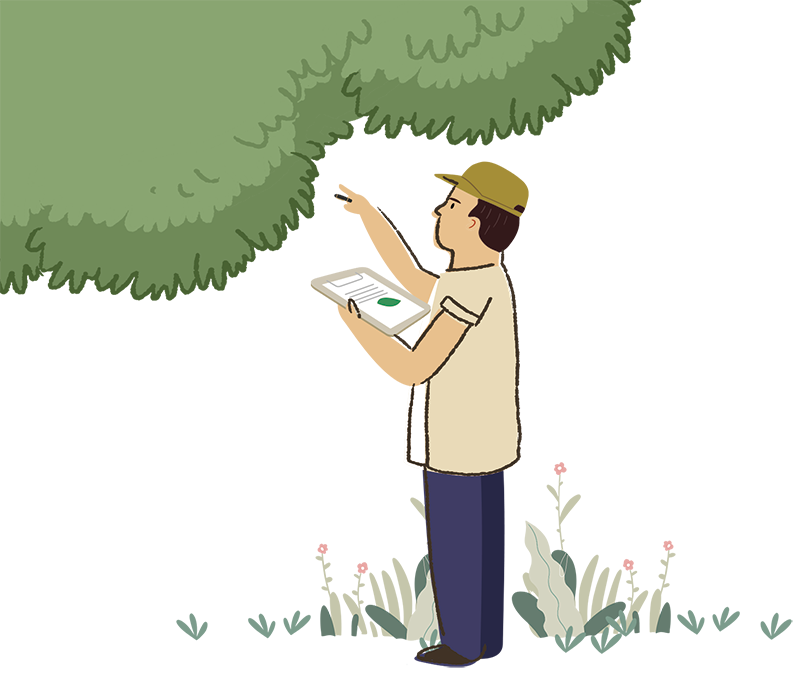

However, after President Tsai Ing-wen apologized to the indigenous peoples in 2016 as head of the state, we seem to have seen a slight crack of the dawn of change. Administrative organizations began promoting changes consciously with administrative discretion, especially the former main opposition against the indigenous peoples, Mr. F, the Forestry Bureau of the Council of Agriculture, Executive Yuan. Since Lin Hwa-Ching, the current director-general came into office, the Forestry Bureau has been working to promote proactive collaborations between forest district offices and local communities, establishing a co-management system.

In terms of hunting, the Forestry Bureau facilitated the “Pilot Project of Self-managed Indigenous Community Hunting”, forming collaborations between forest district offices and indigenous communities in each district. Together they can establish regulations that better accommodate the rules and requirements of local indigenous communities, and in turn, replace the one size fits all rigid management system currently adopted. Furthermore, with cooperation from academic organizations, we can monitor the wildlife population so that the indigenous hunting culture can become a part of wildlife conservation rather than against it.

This year, the Forestry Bureau issued the Regulations on Indigenous Peoples Gathering Forest Products According to Traditional Lifestyles, providing indigenous peoples with detailed legal protection for the necessary gathering activities of daily life, and no longer labeled as crime or theft. In the future, indigenous peoples will be able to apply legally to gather wild plants and trees for their livelihood, with small amount uses exempt from the elaborate process of application.

Such changes showed the indigenous peoples the good faith of the current government in promoting indigenous rights, but administrative efforts without amendment of laws and regulations will only be transitional, failing to solve the real issue. Raise public awareness about indigenous issues, get to know indigenous cultures, and understand that the value of indigenous life is deeply rooted in the cultural context, that is how we can eliminate the discrimination and prejudice in the society towards different peoples, and further create a harmonious society.

To quote the press release by the United Nations on the International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples on August 9, 2018, “protecting indigenous peoples' rights is protecting everyone's rights.” Using the local wisdom of the indigenous peoples to establish management systems and regulations does not make the indigenous peoples “privileged”, rather, the experience and way of thinking connected to the land will help everyone living on this land march towards a better future together. Stop making indigenous peoples wander on our own lands, and stop making indigenous peoples strangers to modern civilization, we should work together with everyone on this land and interpret civilization in our common, diverse and local ways.