Above: Following the teachings of his ancestors, Wilang built a traditional Atayal family house at Nan'ao Township where he currently resides.

"Since I was little, I've always known I am a child of Haga Paris Community, even though I live in Wuta." said Wilang Mawi,

as he walks into the traditional Atayal family house he built himself. He currently lives in Wuta Community in Nan'ao Township, Yilan.

It is said that Wilang's ancestors originally lived in the wilderness between Renai Township in Nantou County and Wanrong Township in Hualien County. Two hundred years ago, the expanding community crossed Nanhu Mountain into eastern Taiwan. They settled along Heping North Stream in Nan'ao Township and were later known as the Nan-ao Atayal.

The Atayal people were forced to move to the plains under Ethnic Relocation policies during the Japanese Occupation Period, and Migration policies launched by the later Nationalist government. The family of Wilang's grandfather was the last to leave their ancestral lands; and because his grandfather stayed there for a longer period of time, Wilang often heard his grandfather talk about their people's history. Going into the mountains with his father and uncles to plant mushrooms and hunt further strengthened Wilang’s strong bond with the mountain wilderness.

However, official history textbooks completely left out any records of the indigenous community members who first came to the area and developed the land, and the migration and relocation incidents. Consequently, the younger generation of Nan-ao Atayals has no idea that these events took place in indigenous history. Unhappy with the situation, Wilang began to write about his family history and memories when he was in university. Ten years ago, he and his grandfather began a cultural investigation project on old communities, hoping to reconstruct the ethnic memory of the Nan-ao Atayal.

Following Grandfather

Back to Old Communities

In 2009, Wilang and his 90-year-old grandfather made the first journey into the mountains to find the old communities. Every trip would require at least one week. The journeys were long, but every trek brings Wilang closer and closer to his community.

After a couple of investigation trips, Wilang gradually learned more about his family history from his grandfather. During the Japanese Occupation Period, the Haga Paris Community was relocated to Hanxi Community in Datong Township because of Ethnic Relocation policies; later a family member killed a policeman, and the whole family was forced to move to the plains. Eventually they found an opportunity to return to their original old community location; but in 1966, the family was forced to move to Wuta Community in Nan'ao by the government.

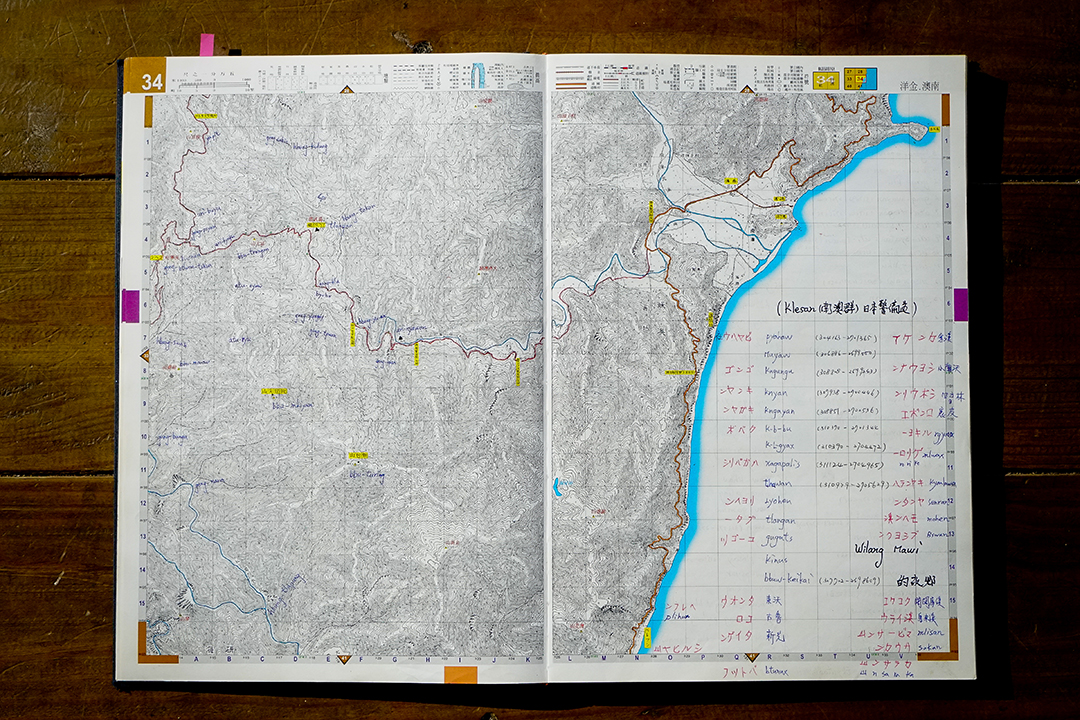

Wilang returned to the mountains at least 20 times in the past decade to do research on old communities. Every trip would take three to four days, or even a month long. In order to document the locations of the communities, he uses GPS equipment to accurately mark the coordinates of the old mountain communities that once belonged to the Nan-ao Atayal on a map. The project has taken him as far as Nanhu Mountain. In 2012, Wilang, his grandfather, and gaga completed the documentary film "Haga Paris", which is about the relocation history of the community. It is a visual record of Atayal life wisdom generated by the people who have been living in the mountain wilderness. Backed with abundant research data and evidence, Wilang can confidently tell the stories of his own community.

Wilang often returns to the old communities to documents their locations. The lower photo shows handwritten notes on Wilang's map.

Building an Atayal Family House

to Carry on Ethnic Memories

Recently, Wilang worked with his uncle and built an Atayal family house in Wuta Community. He proudly claimed that "we indigenous people do not like to cut down trees. The heavens will provide us with the wood we need." He collected fallen cypress wood at the downstream area of rivers and used them as beams, pillars, and the roof girder. The rooftop waterproof fabric is made with smoked cypress bark which keeps the house nice and dry even during typhoon days. Wilang brings his Wuta Elementary School students here to teach them about traditional houses, and his wife teaches cloth weaving at home.

Back home, Wilang often thinks about the times he went hunting in the mountains with his uncle as a child. His uncle will make a fire at night, use Formosan Sugar Palm leaves as a blanket to keep little Wilang warm, and tell him to wait inside the house. Then his uncle will walk alone into the dark forest with his weapon. Every time Wilang would fall asleep waiting for his uncle to return; but at daybreak, he will wake to rustling footsteps and see his uncle, looking tired yet proud, standing in front of him with dozens of flying squirrels on his back.

"The Atayal people are part of the wilderness. That is where we belong." Taking out a jew's harp, Wilang starts to play a powerful and rhythmic melody in his Atayal home. It is a piece his ancestors played to communicate when they were out hunting. It is also a way for Wilang, the bearer of culture and traditions, to pay respect to the ancestral spirits and mountain wilderness.