Above: In 2016, Taitung Bunun Youth made the first trip to hahaul to map the terrain.

You can find Haiduan Township at the end of Provincial Highway No. 20, Taiwan's “most beautiful highway”. Three hundred years ago, this Taitung County township beside the Central Mountain Range was the first Bunun settlement. The old communities here were gradually abandoned after the 1930s, due to relocation policies during the Japanese Occupation Period, but you can still find many old houses on the mountain tops in Haiduan.

Attempting to rediscover the old lifestyle of their ancestors, Bunun youths Langus Lavalian and Aziman Takisdahuan, along with Langus' husband Xie Bo-gang, began to visit old communities to create 3D maps of communities locations and floor plans of old family houses. They are not only documenting the traditional territory of communities, but also rediscovering memories of events that happened on this land.

Three young people from Taitung Bunun Youth record the memories of their people through means they are familiar with.

Creating 3D Maps and

Marking Community Traditional Territories

The idea of returning to old communities began with Langus' journey to seek her family roots. In 2013, Langus asked her father to take her back to old Wulu Communities. When she saw the remaining foundations of the stone slab houses, she became very emotional. “That was the first time I saw the old community and stone slab houses. I wanted to know how my ancestors lived there.” Langus lived her whole life in the community until she left for university, and returned to work at the Bunun Cultural Museum of Haiduan Township after she graduated. She is not completely unfamiliar with her community, but “after that visit in the mountains, I really began to look into my family's migration history. I realized my ancestors moved here from higher mountain areas.”

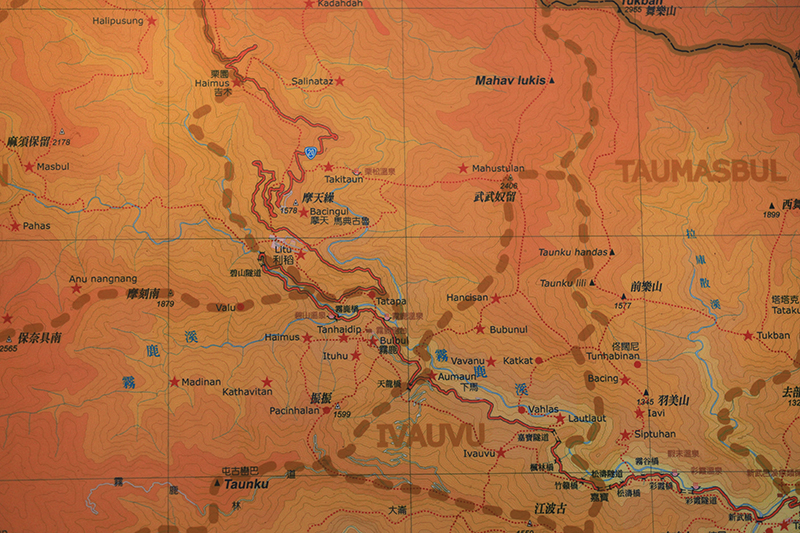

The map at Taitung Bunun Youth records important data such as communities locations.

Langus often made 3D maps of community locations when she was studying in graduate school, turning 2D photographs into layered 3D topography models. “The elders recognize these 3D visual representations of our communities easier than google earth.” In 2015, the trio established Taitung Bunun Youth (TBY) with a couple of other partners. They added Aziman's Sulaiyaz Community onto the 3D map and actually visited Mamahav, the old Sulaiyaz Community. “And along the way the map just grew and grew.” Xie Bo-gang said with a laugh, “starting from Wulu Community, then expanded to the upstream and downstream areas of Sinwulyu River.”

The huge map is 2 meters long and 1.2 meters wide, and with the information collected during interviews with the elders, they created a fascinating oral history of the community. “It's inspiring to see the elders pointing here and there, identifying each other's communities.” recalled Aziman with a smile. He is currently teaching at East Bunun Community School Indigenous Education Center.

The 3D map model of upstream Sinwulyu River, made by Taitung Bunun Youth.

A Cultural Journey

to Bring People Back to the Old Communities

In addition to creating a 3D map, the trio began to document family houses in 2016. They measure the size and space of the houses with a plane table and draw out the floor plans. Xie Bo-gang, who is currently studying for a PhD in anthropology, brought in two younger classmates to help out. “Spatial analysis can offer a lot of information which we cannot get from interviews. For example, how the elders chose the location to build a house, and its surrounding vegetation and ecosystems.”

Gathering data is only the first step, as the three also wish to bring people back to old communities. In 2018, Chulai Elementary School students came to Mamahav for a 3-day, 2-night traditional culture camp. They learned traditional wisdom and skills such as locating water sources, making a fire and cooking, and field dressing. At night they sit beside family houses with no electricity and enjoy the atmosphere of mother nature. “We want them to know the traditional Bunun lifestyle. Our ancestors were not just "surviving", they were "living".” explained Aziman.

Every trip into the mountains is a full train course for "minbunun" ("to

become a Bunun").

Besides visiting old communities, the three continues to explore traditional cultures through various activities. Langus learned traditional weaving, and Aziman began to grow millet in the fields. “Although I grew up in the community, I've never had millet until I went to university!” The farm work is an opportunity to reintroduce traditional foods and also learn about Bunun millet culture. When asked about the objectives of these actions, “we want to fill in the 50-year blank in indigenous history,” Xie explained, “starting from when the Japanese colonial government moved our community members from the mountains, to the assimilation policies launched by the Nationalist government.”

Aziman stressed that “we learn about our traditions not because we want to return to the old lifestyle, but to seek and understand their core spirit and value. We want to explore the meaning of being Bunun in the modern world, and eventually figure out ‘what kind of life can we live as Bunun people?’ ”. This is an open question with endless possible answers, and the trio's actions are a bridge which allows us to look to the future while standing on the roots of tradition.