Why does the government grant indigenous students extra examination points?

Has the entire indigenous education policy

further alienated indigenous people from their culture and identity by default?

The resentment lies deeply in their subconsciousness-

“The extra points make me dislike my own indigenous identity.

The government has no place in making the decision for me

with regard to my college entrance exam score.

I am just as capable as everyone else!”

In 1944, before the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan, it enacted the Regulation on the Preferential Treatment of Students from Frontier Regions in mainland China; thus the regime extended the scope of this regulation to make indigenous peoples of Taiwan also eligible for the preferential treatment in education. This is also the earliest educational affirmative regulation in Taiwan.

The Presumable Good Intentions

from the State

When an ethnic group holds culture and language that are different from Non-indigenous people and resides in a region not populated by the Non-indigenous as the majority, the group would be identified by the Nationalist government as a people requiring support from affirmative educational policies. Although the education policies for indigenous peoples were put in place around the 1950s to ensure equal access to education in general, here education solely means teaching materials based on the Non-indigenous body of knowledge. As common language and culture are powerful tools to drive national solidarity, to firmly establish its regime, the Nationalist government quickly introduced enforcement rules and guidelines for Mandarin based curriculum after Japanese government withdrew from Taiwan.

In 1949, the displaced Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan and enacted Education Guidelines for Upland Peoples. The first article of the guidelines stipulates clearly that “Mandarin based education should be thoroughly enforced to enhance a sense of national solidarity.” In 1951, Directions on Upland Governance, a specific policy regarding indigenous peoples, was announced. Article 20 of the directions specifies that “Mandarin and Chinese should be actively promoted and encouraged with all kinds of effective measures to encourage upland peoples' interests in learning Mandarin and Chinese. The progress of the effort is to be stringently supervised and validated.” Therefore, measures like waiver of tuition and examination, guaranteed school entrance, education subsidies for upland regions have become de facto propaganda disguised in the name of education policies.

Mandarin driven policies were churned out one after another. And of course, statistics indicated improvement of indigenous people's integration into Non-indigenous education system. However, the Mandarin only policies marked a long dark age for indigenous cultures and languages as they thoroughly undermined and degraded native languages.

The state facilitates indigenous integration into the mainstream society by removing language and cultural barriers. Once homogeneity is achieved, then indigenous people will no longer be the special ones who need help. However, where does that idea of integration as the prerequisite of a competent person come from?

Would Everything be Alright

If Education Affirmative Measures Include Indigenous Language Proficiency Certification in its criteria?

In 1987, with the lift of Martial Law, Taiwan saw the rise of local cultural identification and ethnic cultures recognition which led to the burgeoning of related educational regulations.

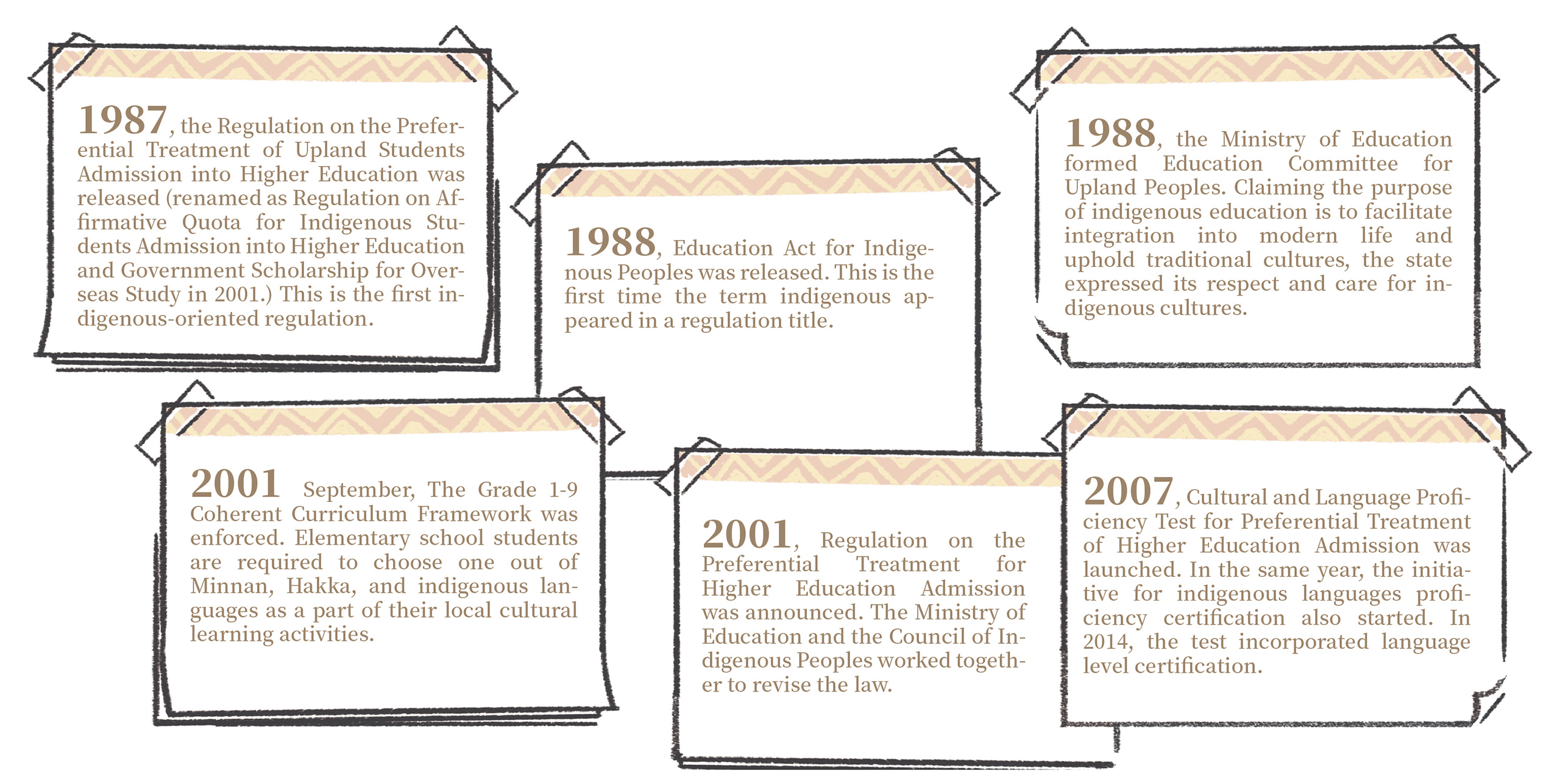

1987, the Regulation on the Preferential Treatment of Upland Students Admission into Higher Education was released (renamed as Regulation on Affirmative Quota for Indigenous Students Admission into Higher Education and Government Scholarship for Overseas Study in 2001.) This is the first indigenous-oriented regulation.

1988, the Ministry of Education formed Education Committee for Upland Peoples. Claiming the purpose of indigenous education is to facilitate integration into modern life and uphold traditional cultures, the state expressed its respect and care for indigenous cultures.

1988, Education Act for Indigenous Peoples was released. This is the first time the term indigenous appeared in a regulation title.

2001 September, the Grade 1-9 Coherent Curriculum Framework was enforced. Elementary school students are required to choose one out of Minnan, Hakka, and indigenous languages as a part of their local cultural learning activities.

2001 ,Regulation on the Preferential Treatment for Higher Education Admission was announced. The Ministry of Education and the Council of Indigenous Peoples worked together to revise the law.

2007, Cultural and Language Proficiency Test for Preferential Treatment of Higher Education Admission was launched. In the same year, the initiative for indigenous languages proficiency certification also started. In 2014, the test incorporated language level certification.

As to whether the affirmative policy of higher education admission for indigenous students should include cultural and language proficiency certification, there are all kinds of opinions from scholars, government officials, parents and the public. The most common and familiar view argues for the justice and fairness for the access to the preferential treatment. On the basis of justice and fairness, when the state tries to uphold cultural subjectivity, indigenous students have to prove that they are competent culturally and linguistically before they are granted the access to the preferential treatment.

Education policies based on this argument have trapped indigenous education in the original dilemma all this time. When those in power ignore the importance of cultural preservation, indigenous people are forced to learn an alien culture and language in order to survive in the contemporary social institution. However, when those in power value the subjectivity and development of of ethnic cultures, indigenous people are required to prove their cultural and knowledge competence for the acceptance of contemporary social institution.

Cultural minority or the culturally unique people alike, the nature of the requirement remain the same. Once again, indigenous people are demanded to prove they are in a position which requires preferential treatment. This no doubt wrongs these people again to the same degree. This reckless link between indigenous language proficiency certification and higher education admission scores made by the government fails showcase the cultural richness of indigenous peoples. Instead, their cultures are rendered plain and dull.

One-sided Decision

Instead of a Choice for All

Since 2001, when Taiwan society embraced the development era of cultural subjectivity, the Ministry of Education continued to promote education policies pertaining to indigenous peoples.

●In 2005, The Five-year Mid-term Development Plan for Education for Indigenous Peoples was finalized.

●In 2011, the Ministry of Education and the Council of Indigenous Peoples together developed The Whitepaper on the Education Policies for Indigenous Peoples and The Five-year Mid-term Development Plan for Education for Indigenous Peoples.

●In 2015, the Ministry of Education and the Council of Indigenous Peoples jointly announced The Five-year Mid-term Development Plan for Education for Indigenous Peoples and The Four-year Talent Development Program for Indigenous Education.

●In 2017, Indigenous Languages Development Act was released. The act established the national language status for indigenous languages.

●Education Act for Indigenous Peoples was amended in 2019 to specifically stipulate the development of ethnic education system should be based on the knowledge body of indigenous peoples.

Given the fact that daily language learning environment is missing from to picture of school based indigenous language programs and indigenous students are further burdened with extra study hours, these programs turned out to be unsuccessful. Education policies in recent years have gradually adopted a bottom-up engagement approach and included more indigenous people into the decision group for teaching material development. An effort of compiling appropriate teaching materials based on the knowledge bodies of respective indigenous peoples also appeared across different disciplines to prepare for future teaching needs. However, with more than half of the indigenous population living in urban areas, there is still a shortage of accredited indigenous language teachers and relevant cultural talents. The shortage of language teachers for those smaller indigenous groups was even more severe.

The lack of talents hinders the effort to enhance indigenous language teaching. In the meanwhile, the long standing affirmative policy for higher education admission also put a strain on indigenous education. In addition to the obvious stigma associated with the preferential treatment for school admission, the extra 2% indigenous student quota for colleges admission, a rule put in place to reduce conflicts between Non-indigenous Chinese and indigenous people, did not work. In fact, after the enforcement of the policy, less indigenous students entered into public universities, where the fee is cheaper in addition to lots of education resources available. Furthermore, the annual household income of indigenous families is 40% lower than the national average whereas the dropout rate of indigenous students is two times higher than the average. It is expected that the dropout rate would only get worse when more indigenous students enter into expensive private universities.

40 years have passed since the introduction of educational preferential treatment after the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan. 2018 statistics show that the tertiary enrollment rate for indigenous students reaches a historical high at 53.9%. However, there is still a 31.9% gap between them and general students. When other people criticize indigenous people taking up resources and enjoy vested interests in affirmative admission policy, they are doing so without realizing that additional points only reinforce the catch-22 faced by indigenous students. It is as if other people are jealous of them driving a new car without noticing their helplessness because the brake is not working and they are trying like crazy to stop the car. “How is that possible that we get better grades than urban students when resources here in the indigenous community are so scarce?” “My dad can only work on odd jobs on construction sites in the city. It's really hard to get by so I have to study like crazy to get into a public university. Otherwise my family cannot afford a private school. This has nothing to do with where I live.” What indigenous students need is to be able to have a say in their education as well as having access to resources that can really help them beside additional points.

Why is it Necessary

to Have Indigenous Education Policy?

Does that mean indigenous education can only help by doing less? The more essential question should be: why do we need ethnic education?

For example, Mandarin driven policy itself is a kind of ethnic education. It is a way for the state to forge national solidarity by instilling a shared identity, recognition and pride as a nation through one language and culture. People of this democratic country need quality ethnic education to foster mature ethnic dignity and at the same time to learn to respect different cultures as they understand that no one culture is better than another. Every culture comes with rich and profound essence. We should not take culture for granted. Culture is the accumulated wisdom of forebears and serves as a compass which leads the way for a nation. Dignity of a nation is acquired by learning to respect ethnic cultures. Mimicking the way indigenous people talk is hardly considered culture at all.

Contemporary indigenous people face a challenge posed by education, standing between science and technology and ethnic knowledge. It is no doubt an inevitable test for all young indigenous people to build a proper bridge accessing wisdom on the two sides. In the face of cultural disruption as a result of more than four decades of ethnic education policies, it is a pressing issue for indigenous education now to catch up and accelerate its pace to effectively document elders' skills and knowledge.

—參考資料—

伊萬納威,〈台灣原住民族政策的發展:透過身份、語言、生計的分析〉,國立政治大學民族學系博士論文,2014年。

林文蘭,〈原住民族人才培育和政策資源:發展趨勢和改革芻議〉,2018年。

教育部統計處,〈107學年原住民族教育概況分析〉,2018。

陳南君,〈進入山地,請說國語 —— 概述1950年代臺灣原住民族國語政策〉,臺北:原住民族文獻,2018年。

趙素貞,〈臺灣原住民族語教育政策之批判論述分析〉,高等教育出版9卷2期:53-78,2014年。