Colonialism and invasion concepts brought forth by imperialism are dismissed as diplomatic power struggles in history. The indigenous peoples who fought relentlessly against the foreign powers, who were forced to migrate and into hiding again and again throughout history lost their culture and roots, and gradually “became Non-indigenous (people)” - this is the basic impression the Taiwanese public has of the plains indigenous peoples.

The History Left Out of Textbooks:

the Kingdoms of the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples

In the 15th century, European countries announced to the world that the development of capitalism will bring forth civilization. Yet the countries were actually expanding their powers and starting trade wars as they discovered new trade routes and embarked on discovery adventures. Taiwan was also unable to escape the fate of being colonized.

In 1624, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) landed on Taiwan at Anping. Using weapons and force, they summoned the indigenous communities and confederations to surrender. Many Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples eventually relented in order to preserve their people and culture, and entered a subject political culture relationship with the Netherlands. In 1645, Tatuturo Confederation was attacked by the Netherlands forces again. But because the neighboring indigenous communities supported the Netherlands, Tatuturo Confederation was forced to sign documents which gave up a portion of their rights. In 1642, the Netherlands armed forces moved south. The attacked Seqalu Kingdom signed the Langqiao Treaty which significantly reducing the power of the village chief.

During the period when imperialism and nation-state ideologies were at their height, forming coalitions or signing treaties with the invaders were only temporary solutions. Indigenous confederations, regardless of size, will eventually have to face the colonizers at their doorstep once they sign the treaties.

The Heroic General of the Non-indigenous People,

the Bane of the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples

In 1661, Koxinga attacked Taiwan. At that time the Netherlands had not yet recovered from the war with the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj and was defeated by Koxinga's army which captured Fort Zeelandia. The Netherlands officially surrendered to following year, ending their 38-years of occupation in Taiwan. The army led by Koxinga continued to colonize Taiwan and called themselves the “Kingdom of Tungning”. While many Taiwanese optimistically view this as the beginning of the development of Taiwan, it was the beginning of the loss of their homeland for the plains indigenous peoples.

Koxinga gave out land to his soldiers to farm when they were not at war. Yet the land he distributed actually belonged to the indigenous peoples already living on the lands, and Koxinga did not conduct any negotiations with the original residents or establish any contracts prior to his policy. To the indigenous peoples, this action was even more offensive and preposterous than the Netherlands colonizers’ land grabbing methods, not to mention it significantly threatened the existence of the Taiwan Indigenous Peoples. The Zheng’s army constantly tried to expand their settlement areas and invade indigenous territories. The Battle of Shalu Village between the Tatuturo Confederation and Koxinga army in 1670 caused massive deaths. In the end only six Papora people survived, and Dadu community members retreated to the mountains and Shuili Village in Puli. Koxinga did not come to Taiwan to rule the island - he occupied it as a base camp for his army to fight against the Qing Dynasty regime.

In 1683, the Qing Empire defeated Zheng and his forces, leading to a rapid increase of non-indigenous immigrants in Taiwan. There were many cases of non-indigenous people trespassing into indigenous territory, conspiring with local gentry to register indigenous lands as “owner-less wastelands” and later change it into private lands owned by non-indigenous settlers. Although the Qing government had laws forbidding the sales of plains indigenous peoples’ land and even set up stone landmarks, but the rights of the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples were usually ignored or even sacrificed by the ruling powers in fear there would be a riot.

Gradually Deprived of Their Sovereignty,

the Western Indigenous Confederation Collapsed

Unlike the Netherlands and Spanish colonizers, Zheng and the Qing Empire completely deprived the indigenous communities of their autonomy and governance, and directly threatened the survival and existence of the indigenous peoples.

The Plains Indigenous Peoples in Central Taiwan

Kept on Retreating

Unwilling to tolerate the greedy officials any longer, the Taokas people in Tunghsiao village initiated the first riot against the Qing Empire's colonizing policies in 1699. The Qing ruling power worked with plains indigenous communities who had surrendered (the Siraya in Xingang area and the Pazeh of Anli village) to suppress the uprising. Discontentment continued to brew among the plains indigenous peoples in central Taiwan due to excessive forced labor and taxes, and eventually in 1731, the Taokas from West Dajia Village started what became a series of plains indigenous peoples’ rebellions. The Qing rulers used both force and incentives to combat the uprisings: they annihilated rebelling plains indigenous communities and burnt everything down to the ground; while on the other hand awarded resources to indigenous communities that surrendered. But the latter policy was not effective.

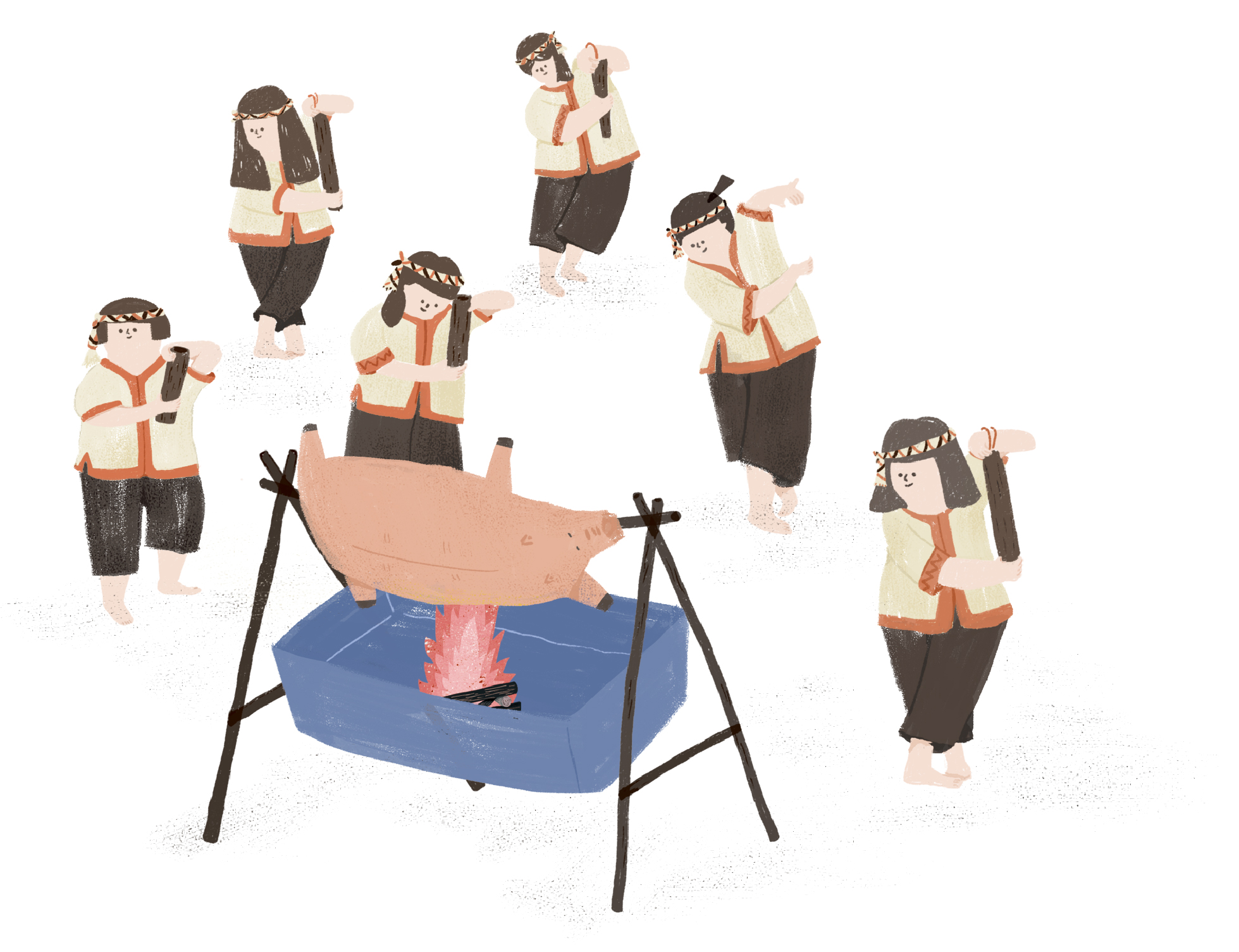

Disgruntled that the non-indigenous settlers had gone too far, the Papora people of Confederation, including West Dajia Village, joined forces with eight other Taokas communities in Bengshan and rebelled the following year. Almost every plains indigenous community in central Taiwan joined in. After seven long months of battle, the Qing government decided to completely eradicate local plains indigenous people forces and publicly beheaded the leaders of every community in Dadu region. The royal house of Tatuturo was destroyed and never recovered, and the rest of the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples were terrified by this incident. Accepting their oppressive fate, they retreated to the Yilan and Puli regions.

Starting from 1790, the Qing regime implemented a new policy which claimed to award indigenous groups with additional land; but in reality, it was a scheme to let indigenous forces counteract each other. The Taiwanese Plains indigenous peoples were assigned to live and settle in the areas between plains and mountains to keep mountain indigenous community members out of the plains. A lot of plains indigenous peoples who originally lived along the seacoast and on the plains were relocated to western low elevation mountains border areas and mountain regions. Afterwards, there were many cases of non-indigenous settlers stealing land from indigenous communities. The Taiwanese plains indigenous peoples in the west faced harder and harder living and farming conditions and eventually moved into Puli Basin. Although they surrendered, the plains indigenous peoples were ultimately forced to relocate and lost their lands in the end. And now their future is still uncertain.

A Later Invasion Did Not Lessen the Damage

A Later Invasion Did Not Lessen the Damage

for the Kavalan in the Northeastern Corner

The Yilan area, which was mainly populated by the Kavalan, was affected by foreign colonial powers much later than other areas due to its location and geographical advantages. In 1796, Wu Sha led a group of non-indigenous immigrants into Lanyang Plain, bring in waves of invading settlers into the area. In 1829, seeing the increasing number of non-indigenous settlers moving into the plain, the Kavalan had no choice but to gradually move to neighboring places, such as Sanxing and Su’ao. But in the following ten years, the Kavalan began to rapidly lose their land. A total of six communities, led by the Karewan people in Dongshan Township, moved to Beipu in Hualien to set up new communities. The new village cluster spread out as far as Tafalong area in the south.

After the Lanas na Kabalaen in 1878, the Qing regime ordered the remaining Karewan community members and the Sakizaya people who were also involved in the Incident to leave their original homelands. The Kavalan people dispersed and hid among the Pangcah, and never formed a unified community again.

Southern Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Communities

Southern Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Communities

Fell as Different Colonizing Power Came

Southern Taiwan was once the home to two large Confederations. In the region above Fenggang River was the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj, established by the Tjaquvuquvulj Village led by upper Paiwan people, and was part of the Up 18 Communities of Lonckjau. In the area below Fenggang River was the Down 18 Communities of Lonckjau established by the Seqalu people. The community was later known as the 18 Communities of Lonckjau.

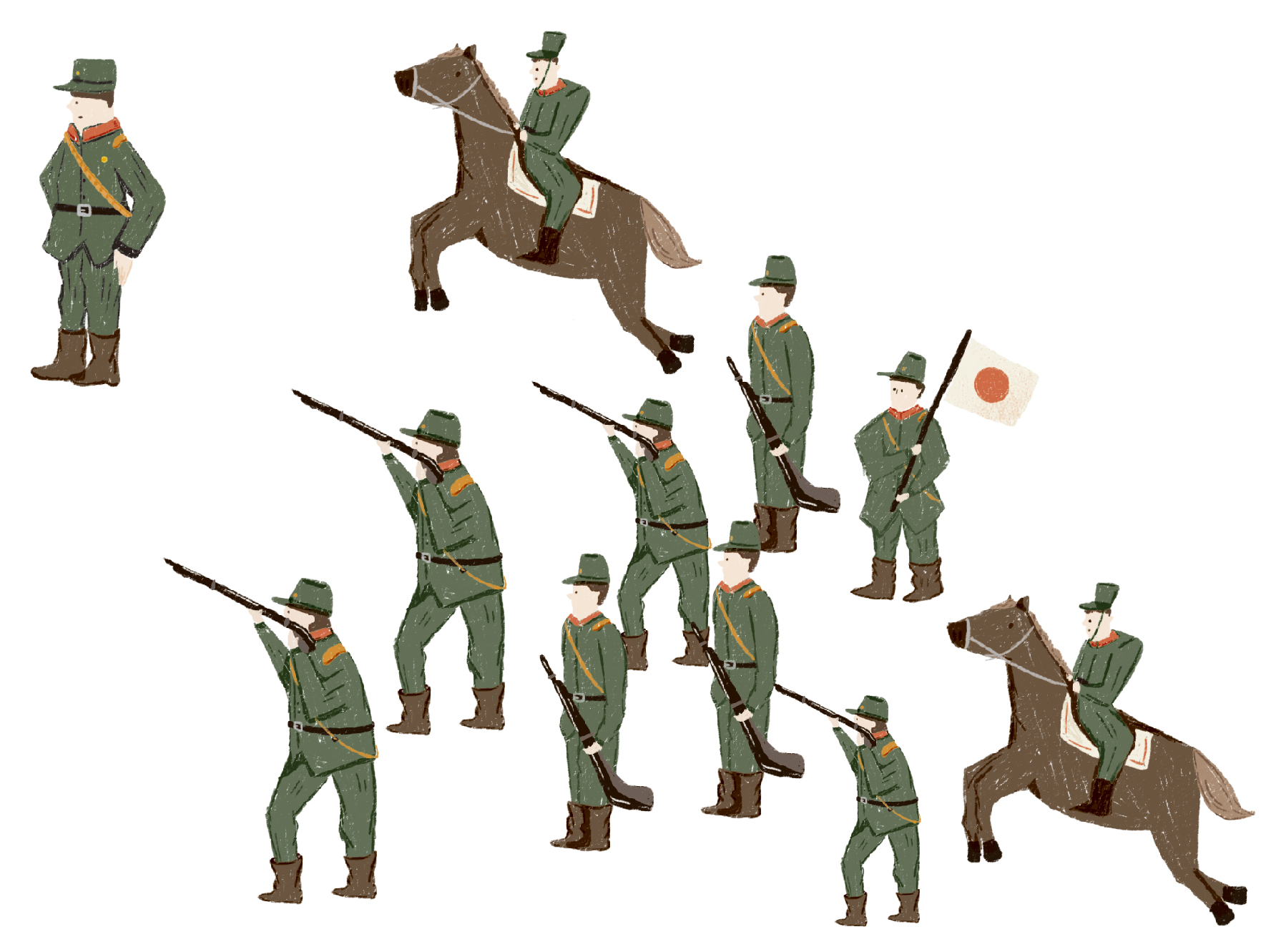

Before 1874, the Qing regime was not interested in governing southern Taiwan. It was not until the Mutan Village Incident and the Japanese invaded Taiwan did the Qing regime realize the importance of Taiwan's strategic location and began to actively colonize the island. As the regime began to enter the mountains and overpower indigenous peoples, they ignited many conflicts and battles; nevertheless, as the colonization period began to stretch out, surrendering and paying allegiance became inevitable for the indigenous communities. The Seqalu communities were classified as “civilized savages” by the Japanese colonizers and in policies, which indicated that the groups were the same as non-indigenous people. However, this categorization quickly reduced the ethnic characteristics, including language, of the Seqalu.

“The so-called ‘civilized savages’ refers to plains indigenous peoples who have assimilated into the non-indigenous lifestyle a century ago and settled in the plains. Now they are living in general administration areas and are as compliant as the other islanders.” Under the assimilation and Japanization education schemes of the Japanese colonizers, the plains indigenous peoples who lived among the non-indigenous were further deprived of their original culture and languages, thus greatly affected by the forces of colonialism.

Seeking the Identity

of Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples

Looking back in history, the name “Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples” originated from the colonizing government's categorization of “uncivilized savages” and “civilized savages”. But this type of classification is not based on any bloodline or scientific factors and merely a convenient method for the regime to manage the peoples. The definitions for mountain and non-mountain indigenous peoples, and “assimilated savage” and “plains savage” were also very vague. For example, the term “plains savage” was used for indigenous people living in the plains, so Pangcah community members living in the plains were also called “plains savages”.

The methods the colonial government used to classify ethnic groups back then affected the lives of later Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples. Community members who once registered as “civilized savages” are not protected by indigenous peoples’ laws since the laws consider civilized savages the same as the non-indigenous people. The distinction between non-indigenous and plains indigenous peoples is unclear, making the identity of indigenous peoples even more invisible.

Centuries have passed, new sprouts appear and grow from the ground under heavy wooden coffins. As history progress and ethnic group relationship issues gradually develop, identity awareness among the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples is a topic that has resurfaced in Taiwanese society. Now we realize that the “Taiwanese plains indigenous peoples” are not only a group of people with a label, but living and breathing indigenous peoples living on this land. The journey to ethnic identity recognition and culture revival has just begun. The younger generations are actively seeking common grounds and reviving their peoples’ culture, rituals, and languages, reintroducing the plains indigenous peoples to the Taiwanese public. It may take a lot of effort to rectify their names, but we should never forget our history and past experiences.

─ References ─

蔡宜靜,〈荷據時期大龜文(Tjaquvuquvulj)王國發展之研究〉《台灣原住民族研究論叢》,6期,p157-192,花蓮:臺灣原住民教授學會,2009年。

康培德,〈環境、空間與區域:地理學觀點下十七世紀中葉「大肚王」統治的消長〉《臺大文史哲學報》,第59期,p 97-116,臺北:臺灣大學文學院,2003年。

楊克隆,〈清代平補足土地流失原由新探〉《興大人文學報》,第61期,p47-78,臺中:國立中興大學文學院,2018年。

楊鴻謙,《清代台灣南部西拉雅族翻攝地權制度變遷之研究—以鳳山八社領域為範圍(1683~1895) 》。臺北:國立政治大學地政學系博士論文,2002年。

黃唯玲,〈日治時期「平地蕃人」的出現及其法律上待遇(1895-1937)〉《臺灣史研究》,第19卷第2期,p99-150,臺北:中央研究院臺灣史研究所,2012年。

詹素娟,〈歷史轉折期的噶瑪蘭人─十九世紀的擴散與變遷〉《臺灣原住民歷史文化學術研討會論文集》,p109-147,臺北:國史館台灣文獻館,1998年。

葉神保Drangadrang Validy,《日治時期排灣族「南蕃事件」之研究》,臺北:國立政治大學民族學系,2014年。

潘顯羊,〈核心部落、核心家族、人群互動關係與整合:近年恆春半島族群文化活動的參與觀察〉《民族學研究所資料彙編》,第25期,p45-98,臺北:中央研究院民族學研究所,2017年。

楊鴻謙、顏愛靜,〈清代臺灣西拉雅族番社地權制度之變遷〉《台灣土地研究》,第6卷第1期,p17-50,臺北:國立政治大學地政學系,2003年。

段洪坤,〈失去土地,怎麼找祖先足跡:吉貝耍西拉雅的土地經驗〉《原教界》,第76期,p58-61,臺北:國立政治大學原住民族研究中心,2017年。

廖志軒、李季樺、劉志強、劉秋雲、李宗信、郭怡棻,〈道卡斯族專題〉《原住民族文獻》,第12期,p2-44,臺北:行政院原住民族委員會,2013年。