As is known to most of us, historically Taiwan has been undergone the successive rule of different foreign forces, from the Netherlands, Ming Zheng, the Qing Empire to Japan. These regimes have had a profound influence on the island, and their governance has contributed to the shaping of its modern-day geographical and cultural landscape. Yet, very few of us are aware that the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples who used to live in central Taiwan were massacred and persecuted during the invasion and colonization of these foreign regimes. To find more chances of survival, they had no choice but to abandon their homelands and relocate to somewhere else.

The Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples are mainly comprised of the Pazeh, the Kaxabu, the Papora , the Taokas, and the Babuza. At present, a group of young descendants of these peoples are striving fearlessly toward revitalization in hopes of rediscovering the history and memories of their ethnic groups that have long been neglected.

The fossilized bones of a mother and baby excavated from Central Taiwan, which can be dated back to roughly 4,800 years ago.

The Prehistoric Origin

of the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples in Central Taiwan

Recent studies by international academic circles have found that Taiwan could be one of the birthplaces of the Austronesian-speaking peoples, while the cultural relics unearthed at the archaeological sites in the Greater Taichung area also indicate that the evidence of ancient Austronesian peoples living there can be dated back to at least 5,000 years ago. Among these findings, one of the most noticeable is the fossilized bones of a mother and baby excavated from what is now called the Anhe Ruins at Taichung’s Dadu Terrace, which are the earliest human fossils ever found in Taiwan and are therefore dubbed as the “most senior resident” of central Taiwan.

Around 1,000 to 600 years ago, the regional development across the South China Sea was peaceful and stable, and the Austronesian nations that formed the island chain were generally strong. The maritime trade thus flourished in the region. Nowadays jade items from Taiwan can be found in the Philippines, Vietnam and southern Thailand, while foreign agate and jade artifacts are also unearthed in the former habitat of the Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples. This indicates the group behavior of these peoples had helped to stimulate their rise as an emerging economic force that maintained long-term stability in the Pacific economy.

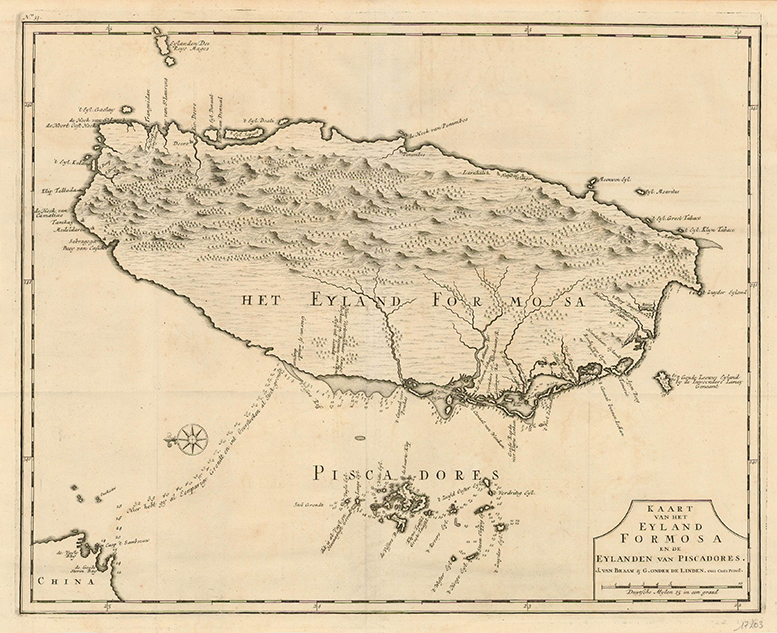

The ancient map of Taiwan drafted by the Netherlands in 1625.

The Tatuturo Confederation

in the Era of Sea Trade

500 years ago, Western European sea powers made their way into the Southeast Asia region, initiating their competition with local sea trade groups (pirates). In 1553, the Portuguese took over Macau, opening the chapter of European economic and trade development in East Asia. Although the Portuguese had stopped by Taiwan en route to East Asia, their logbooks did not contain any description of the Tatuturo Confederation in central Taiwan back then. In 1573, the Chinese pirate group led by Lin Feng grew in power across the Taiwan Strait, and was constantly looting the nearby coastal areas. Later it was besieged and routed by the Chinese officers and soldiers from Fujian, fled to the Penghu Islands, Wanckan (today’s Budai Township of Chiayi County), and China in succession, but never stopped by the coastal area of central Taiwan. They were said to have deliberately avoided the domain of the Tatuturo Confederation, to which they were not allowed to come ashore.

The Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), one of the Western sea powers, came to Taiwan in 1624. Back then, the Kingdom of Tatuturo was under the leadership of Kamachat Aslamie. “Kamachat” is the respectful form of address to the king, while “Aslamie” one of the traditional names of the Papora people. The indigenous villagers referred to their king as “Lelien,” which means “the King of Middag” or “the King of Sun.” The term has its counterpart in today’s Pazeh language, “dalian,” which means “midday.” The Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples employed such a form of address to praise the strength of the kingdom and the exalted status of its leader. It is also thanks to the preservation of the Pazeh language that the term “Lelien” remains imprinted in the memories of the Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples throughout generations.

The landdag (“country assembly”) on Netherlands Taiwan. As historical records show, the King of Middag had partook in the southern country assembly held by the VOC. From this we can see that the king had played an important role under the Netherlands colonial rule.

According to the records of Scotsman David Wright and The Daily Journals of Fort Zeelandia, during its heyday the kingdom of Tatuturo had up to 27 communities under its rule, the dominion running south to Lugang and north to Taoyuan. Exactly under the jurisdiction of the kingdom were 18 communities, which, compared to today’s Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples, included four major ethnic groups: the Papora people (the communities of Dorida amicien, Dorida babat, Dorida mato, Bodor, and Babusaga), the Babuza people (the communities of Asock and Tavokol), the Pazeh people (the communities of Tarranongan and Aboan Auran), the Arikun people (the communities of Tausa Talakey and Tausamato), and so forth. It can be said that almost the entire central Taiwan region had fallen within the kingdom’s jurisdiction. A Dutch John Struys had even mentioned in his travelogue that “the most affluent place in Taiwan is ruled by King of Middag.”

The Netherlands and Spain arrived in Taiwan successively in 1624 and 1626. Since then each of them had occupied the southern and northern parts of the island respectively for 14 years, but never met in the central region. From this we can see how powerful the Tatuturo Confederation was at that time. According to the Netherlands literature, King of Middag had set up rules across the territories under his jurisdiction stipulating that Christians were prohibited from dwelling in his dominions, that they had to learn the kingdom’s lingua franca, and that missionaries could not make any stay when passing through the confederation. To consolidate its sphere of influence the confederation employed a two-fold strategy: Internally, it imposed restrictions and control over foreign religious activities, while externally establishing economic ties with foreign forces by trading such goods as deerskins and stones. These practices continued until 1662, when the Netherlands were expelled from Taiwan.

The Fearless Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples

in the Face of Foreign Forces

On April 30th, 1661, Zheng Cheng-Gong (Koxinga) led armed forces ashore to Luerhmen, Tainan, and took control of the Tai-jiang Inland Sea. In July, A Tek Kaujong (aka Maloe)1, the leader of the Tatuturo Confederation, led his people to fight against Zheng’s army and won the battle eventually. Yet A Tek Kaujong himself was killed in the ambush. This hard-won victory brought about a dramatic change to the Confederation’s fate.

In 1670, Liu Guoxuan was sent by Zheng Jing, Koxiga’s successor, to attack the Passoua community, the traditional territory home to the Babuza people, in order to expand the regime’s territorial control. The invasion was met with the resistance of multiple communities within the Confederation, including Tatuturo, Salagh, and Tarranongan. The battle was so large that even Zheng Jing participated personally. Hundreds of residents of the Salagh community were killed by the enemy, leaving only six survivors fleeing to the seaside. Some people from the Tatuturo community were chased by Liu’s army to the Xingang River (today’s Guoxing Township) and eventually fled into Puli. This conflict is historically known as “The Battle of Salagh,” which marks the first time that the Tatuturo Confederation had suffered a mass slaughter. It also foreshadowed the mass migration of Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples to Puli thereafter.

The massacre and exploitation of Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples by Zheng’s regime resulted in the decline of the Tatuturo Confederation. As is recorded in Hai Shang Shi L?e (A Brief Record of Sea Affairs), the Taokas people in the communities of Torovaken and Pocaal were enslaved by Zheng’s army, who whipped them ruthlessly simply because they were not used to carrying heavy loads on the shoulders like non-indigenous people did. Hence, there was a popular song in the Torovaken community that goes like this: “Zheng Cheng-Gon relentlessly subjugated the barbarians in and nearby the Torovaken community, killing countless untamed people.”

The year 1699 saw the first indigenous revolt against the Qing government officials launched by Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People. The incident was triggered by the Parrewan community of the Taokas people, who were infuriated by the autocratic style of management of Huang Tung, the translator and liaison between the indigenous communities and the Qing government. In 1722, there were two other large-scale joint anti-government operations: The Battle of the West community of Taokas in 1731, and the Incident of the Tatuturo Community in 1732.

In December 1731, as the Qing government assigned excessive physical work over a long period of time, the West community of Taokas decided to stage a revolt. The operation was joined by over one thousand indigenous people from the eight Pangsoa communities, targeting the Qing’s coastal defense office located at the Salagh community. Later several communities of the Papora and Pazeh peoples, including Salagh, Gomagh, Aboan balis, Aboan Pali (now self-proclaimed kaxabu), also joined the battle. The revolt ended up with over 200 houses in the Aboan Pali community destroyed by the fire and a heavy toll of deaths and casualties.

In 1732, to take credit for suppressing the uprising, a relative of the Qing official Ni Xiang-Kai, who had quelled the disturbances, decapitated 5 indigenous people who came to help with the transport of provisions, falsely claiming them as “uncivilized barbarians who went on the rampage.” This infuriated the communities of Dorida mato and Salagh, who joined hands with other communities from the former Tatuturo Confederation to launch a revolt, the members including the West and East communities of of Taokas, Tanatanaka, Waraoral, Maoyu (the Taokas people), Asock, Baberiengh (the Babuza people), Aboan balis, and Aboan Pali (the Pazeh people). The scope of this uprising extended as far as to the Chu-lo border, covering an area nearly one thousand miles in radius, and involving over 50 indigenous communities.

In 1732, to take credit for suppressing the uprising, a relative of the Qing official Ni Xiang-Kai, who had quelled the disturbances, decapitated 5 indigenous people who came to help with the transport of provisions, falsely claiming them as “uncivilized barbarians who went on the rampage.” This infuriated the communities of Dorida mato and Salagh, who joined hands with other communities from the former Tatuturo Confederation to launch a revolt, the members including the West and East communities of of Taokas, Tanatanaka, Waraoral, Maoyu (the Taokas people), Asock, Baberiengh (the Babuza people), Aboan balis, and Aboan Pali (the Pazeh people). The scope of this uprising extended as far as to the Chu-lo border, covering an area nearly one thousand miles in radius, and involving over 50 indigenous communities.

These two conflicts lasted for three years and were Taiwan’s largest mass rebellion across indigenous peoples in history, which made a profound impact on the subsequent development of Taiwan’s ethnic groups.

From these large-scale anti-Qing operations of Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples, we can find that these communities of multiple ethnic groups maintained a close tie with one another and had outstanding organizational abilities. The related literature also shows that they seldom battled with each other vying for hunting fields. They had maintained a fairly stable and friendly relationship for thousands of years. In the battle with the Parrewan community in 1699, the Qing court chose to send Tainan’s Siraya people northwards to help subdue the rebellious Taokas people instead of mobilizing the nearby Babuza communities. This evidently suggests that the Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples still kept on good terms and maintained a certain degree of intimacy during the Qing dynasty. It is such unique connection and cohesion that contributed to the largest mass migration of Indigenous peoples in Taiwan’s history.

The Largest Mass Migration

of Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan's History

The year 1814 saw the invasion of the Puli Basin by non-indigenous people led by Guo Bai-Nian, resulting in heavy casualties in the indigenous Puli community. This is known historically as “the Guo Bai-Nian Incident.” In order to protect the Basin from the non-indigenous people’s constant invasions, the Puli community, through the introduction of the Thao people, invited the Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples who had suffered a great loss of their territories to move inland to the Puli Basin. This initiative marked Taiwan’s largest mass migration of Indigenous people in history, including the following ethnic groups:

▴The Papora People: the communities of Tatuturo and Bodor

▴The Taokas People: the communities of Tanatanaka, Waraoral, Varaval, and Parrewan

▴The Babuza People: the communities of Dobale, Babousack and Tarkais (Gilim)

▴The Pazeh People: the communities of Aboan Auran and Aboan balis

▴The Arikun People: the communities of Tausa Talakey, Tausamato and Wandouliu

▴The Lloa People: the communities of Talack and Badsikan

▴The self-proclaimed Kaxabu People: the communities of Varrut, Karahut, and Tarawel

A total of 30 communities relocated to Puli and continued to use their original names in the new settlements, such as Waraoral, Aboan Auran, Tatuturo, and so on. They also referred to each other as “Taritsi,” which means allies and relatives.

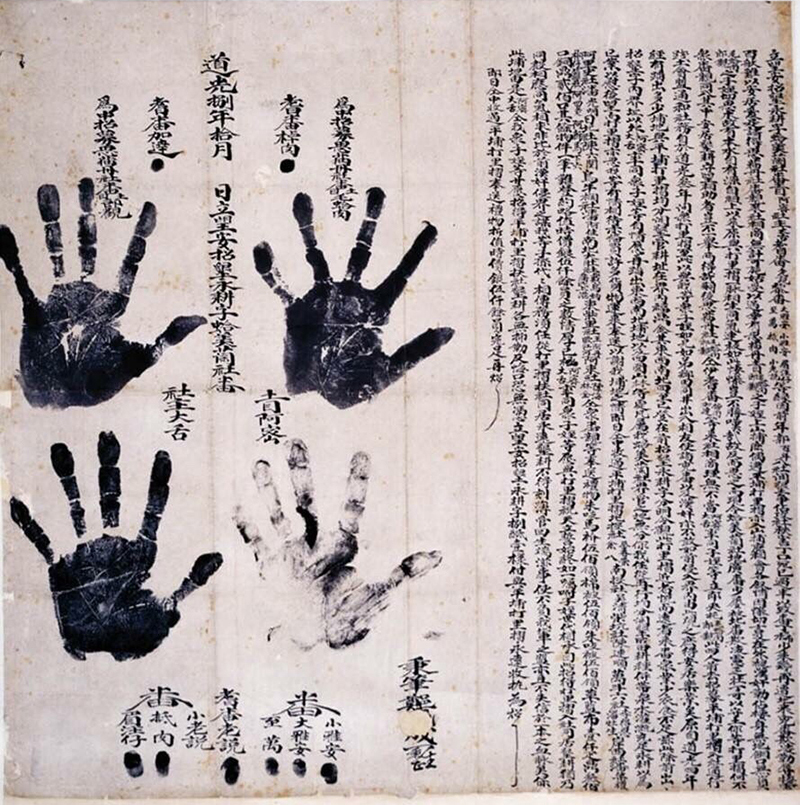

The settlement contract of the Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples migrating into Puli. This contract is signed between the communities of Kabilan (Pu-li Village) and Kankwan.

In many historic records of allotment agreements found in Puli, we see that these immigrant communities also signed settlement contracts that stipulated the shares of land for use. The land was divided in proportion to the size of each community. Such practice bore witness to the harmonious partnership between the Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples. Also, in order to express their gratitude to the Thao people for introducing them into Puli, the descendants of headmen from each ethnic group developed a tradition of presenting them with such gifts as “pulled rice cake”, rice wine, and pork annually, which has been passed down to the present day. Such a custom is called by the Thao people as “rice cake picking.”

Continuing Ancestral Cultural Legacy

that Lasts for Thousands of Years

Despite the fact that they had moved away from their homelands, the Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples did not abandon their languages and still continued their traditions in Puli. However, their culture was faced with suppression by the Japanese colonial rule, under which the indigenous languages and rituals were forbidden for the sake of the assimilation policy. The Japanese officials even humiliated indigenous residents by ridiculing them publicly at their festivals. The Pazeh elders recall that back then village elders who spoke their mother tongue were brought to the police station and got punished. It is such a dire situation that led to the decline of traditional cultures among the Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples.

Looking at the traditional Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples’ cultures in terms of food, we see that many communities in Puli share a custom to make a special kind of rice cake as the offering for worshipping their ancestors. The rice cake is made by mixing grounded bur grass with glutinous rice paste, which is to be steamed and wrapped in yuetao (Alpinia) or banana leaf. This dish has a different name in each ethnic group: In the Taokas it is called “hinpu,” while in the Pazeh “umu,” and in the Papora “tutu.”

The Distinctive Culture of Each Ethnic Group

The Distinctive Culture of Each Ethnic Group

The Papora

The Papora’s “Daducheng” community in Puli hold the traditional “Alomai” ceremony in worship of ancestral spirits annually on the first day of the seventh lunar month. The ritual begins with community members calling out for their ancestral spirits in the ritual area, who are then carried back to the community on the backs of their descendants symbolically to pray for peace for the village. Solemn and sacred, the ceremony is held exclusively within the community and has never been open to the public, which shows how serious the Papora people are about their traditional culture and ritual ceremony.

The Taokas

The Torovaken community maintains a more complete ritual culture of the Taokas people. The “Chian Tien” Ritual (牽田祭) is held annually from the 15th day of the seventh lunar month to the 15th day of the next lunar month. The community members have to make three huge flags representing the ancestral spirits one month ahead. The flags are about 1.8 to 2.1 meters tall and are to be carried respectively by a “issama” (flag bearer) on the back to march around the ritual area. During the procession each issama is assisted by two flag guards to prevent the flag from falling. As the flag symbolizes the community’s highest respect for and belief in their ancestral spirits, the Taokas people believe that if it falls, there will be misfortunes to the village.

The Babuza

The Babuza’s Dobale community also holds the Chian Tian Ritual to worship ancestors, which falls on the evening of the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. Unlike its counterpart in the Taokas communities, the ritual here is held on a household-basis, and the tradition has continued until the present day.

The Arikun and the Lloa

The communities of the Arikun and Lloa hold their ancestor worship ceremony on the 20th day of the seventh lunar month. Today they still maintain the ritual of worshipping the ancestral spirits in front of the red cedar in Puli.

The Pazeh and the Kaxabu

The Pazeh and the Kaxabu peoples share a brotherly kinship in their culture. They both celebrate “Azem,” the traditional new year, on the 15th day of the eleventh lunar month. On the day of the ritual, people dance and sing the ancient chant of “Aiyan,” which tells the story of their origin and remembers the spirits of ancestors.

As far as language is concerned, thanks to the introduction of Western religions, the Pazeh and the Kaxabu languages are better preserved through the documentation of churches. Now they are the only two of Taiwanese Indigenous Peoples who are yet to be recognized officially that have developed their own language textbooks with 9 levels of difficulty. Nowadays, in Puli’s Suwanlukus community, one can still find elders who can talk fluently in their native tongue. In recent years, the Taokas people has published their own dictionary: Matitaukat(Matitaukat Taokas Dictionary), while the Arikun and the Lloa peoples are increasingly striving to get rid of the traditional tag of Hoanya in hopes of rectifying their names. The Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples have enjoyed a close bond of friendship that ran far and deep in the course of history. Likewise, their contemporary descendants are working steadfastly in their own ways for the continuation of traditional cultures.

Despite the 400 years of suffering of colonization, the Central Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples have never abandoned their responsibility of continuing their cultures. They also place much emphasis on the pursuit of the rights for their younger generations and have been active in such civil rights campaigns as the Aboriginal Land Movement in Taiwan, and the Name Rectification Movement of Taiwan Indigenous People. Over the past two decades, these peoples, following in the steps of their ancestors, kept asking the government to return the basic human rights they deserved. Recently, such an appeal has been further carried on by the Central Taiwan Plains Indigenous Groups Youth Alliance, which is established by young members of the seven major ethnic groups of the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples in central Taiwan. The aim of this cross-ethnic collaborative organization is to continue their traditional ways of life that have been passed down over centuries, and to regain self-confidence and pride of being indigenous people of the island of Taiwan.

Descendants of the Arikun and the Lloa peoples hold the ancestor worship ceremony in front of the tree representing their ancestral spirits. Photo courtesy of Deng Xiangyang, an expert on Puli’s local history.

The protest for the name rectification of Taiwan Indigenous Peoples organized by the Central Taiwan Ping-Pu Indigenous Groups Youth Alliance.

Members of the Central Taiwan Ping-Pu Indigenous Groups Youth Alliance attend the Kaxabu people’s New Year celebration, which bears witness to their close friendship.

The Taokas people’s “Chian Tien” Ritual held in Torovaken community.

N.B.1 : Maloe is also known as A Tek Kaujong, which tended to be transliterated as “阿德.狗讓” in Chinese historical records. Such translation is deemed discriminatory with a sense of disparagement implied by the word choice of “狗” (dog). After comparing the Netherlands literature and their traditional naming system, the modern Papora people consider it more appropriate to replace “阿德.狗讓” with “愛箸˙加勞” to show respect for this legendary king of the Tatuturo Confederation.

—References—

劉益昌,《考古學與平埔族群研究》,平埔族與台灣歷史文化論文集,臺北:中央研究院台灣史研究所籌備處,2001年。

林景淵,《濱田彌兵衛事件及十七世紀東亞海上商貿》,臺北:南天書局,2011年。

翁佳音,〈被遺忘的台灣原住民史——Quata(大肚番王)初考〉《臺灣風物》,臺北:臺灣風物,1992年。

康培德,《環境、空間與區域:地理學觀點下十七世紀中葉「大肚王」統治的消長》,台大文史哲學報,臺北:臺灣大學文學院,2003年。