In the remote past, our ancestors lived in harmony with nature and all creatures, believing that every living thing has a soul. This belief forms the basis for the animism shared by all the indigenous peoples. Community members who are endowed with special energy are selected as shamans to communicate the words of spirits and solve problems for their fellow villagers. These shamans play a pivotal role in maintaining the order of their communities.

Medium, priest,

or shaman?

In Chinese, “wu” (shaman) refers to a person who can connect with gods and the spirits to pray for their blessings or healing, while “Ji” (ritual) focuses on the actions performed as part of worshipping ceremonies. A shaman is defined specifically as one who can communicate with gods and spirits. To become a shaman, one must receive a sign indicating their “preordained fate”. For priests, on the other hand, there are usually no restrictions on their identity or status, and they can be trained to conduct various rituals and religious ceremonies. Due to the differences in beliefs and functions, the term for a person with spiritual abilities may vary among different indigenous communities, ranging from shaman, priest, to medium. The term “shaman-priest” is also adopted by some scholars.

Summoning a Shaman!

Terms for Shamans in Various Indigenous Cultures

and Their Duties Explained

Paiwan: pulingaw、malada

Conduct rituals, dispel infestation or disease, and dispel calamities.

Pangcah: sikawasay

Conduct rituals and ceremonies, pray for blessing, treat illnesses, and dispel calamities for the villagers.

Thao: shinshi

Host rituals and ancestor-worshipping ceremonies on occasions such as wedding, funeral, and house construction and demolition.

Siraya: inibs

Host rituals, dispel evils and calamities, treat illnesses, do divination, and maintain the environment of kuwa (shrine).

Kaxabu

katuhu: Heal illnesses and wounds.

daxedaxe: Able to fly, cast spells.

The Making of a Shaman

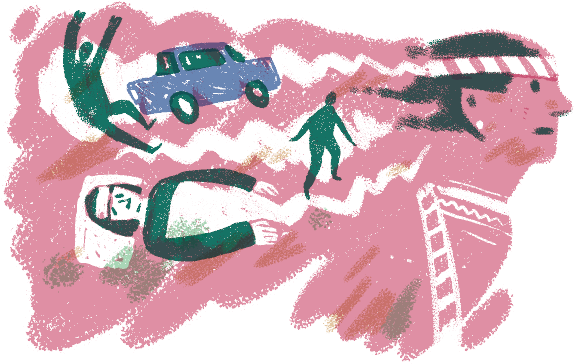

Most shamans are born to their roles. In some indigenous societies, like Paiwan, shamanhood is passed on through hereditary succession and a “master-apprentice” system. Clansmen who are endowed with spiritual abilities or those who are interested in the trade are selected as candidates. They then have to learn from a master shaman and pass a series of special tests given by the spirits before getting qualified as a successor. The training process is described as follows:

Step 1.

The spirits will make the chosen one to fall into a series of mishaps, such as getting seriously ill for no reason, having a major car accident, or undergoing a near-death experience, to give him/her a hint of their potential. To dispel these calamities, he/she has to go through a formal ritual of shamanic initiation, which would otherwise result in life-threatening mishaps.

Step 2.

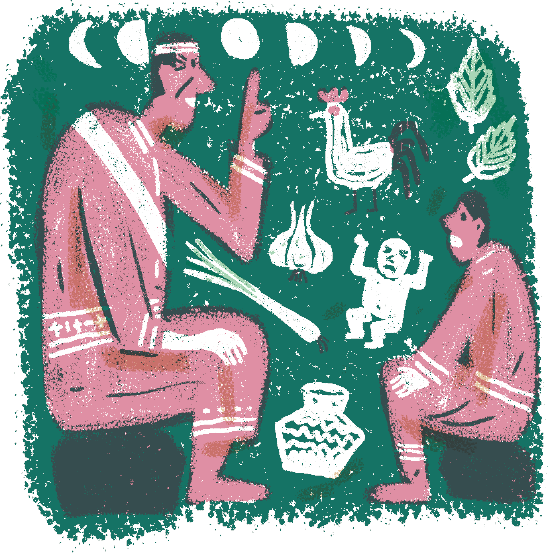

A solemn “god-descending” / testing ceremony is held. The chosen candidate becomes an apprentice to the village’s shaman to study knowledge about traditional rites and rituals.

Step 3.

A certified shaman must abide by shamanic taboos and disciplines for the rest of his/her life. For example, a Pinuyumayan shaman from Puyuma village in Taitung has to live separately from his/her family in a designated house, while Pangcah shamans must refrain from eating green onion, garlic, and chicken throughout their lives.

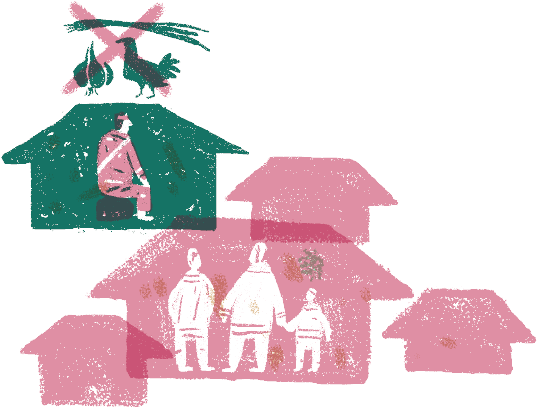

A Profession that is Open to Both Genders

Since shamans are usually born with a destined mission, they could be chosen by the spirits regardless of identity, social status, and gender. But conventionally, it is women who are selected for such a role. The Paiwan people, for example, is known to have only female shamans, or malada, as is called in the Paiwan language. Scholars speculate that this is because a shaman’s duties are mostly centered around traditional ceremonies related to the harvest of millet, rather than the male-dominated hunting rituals.

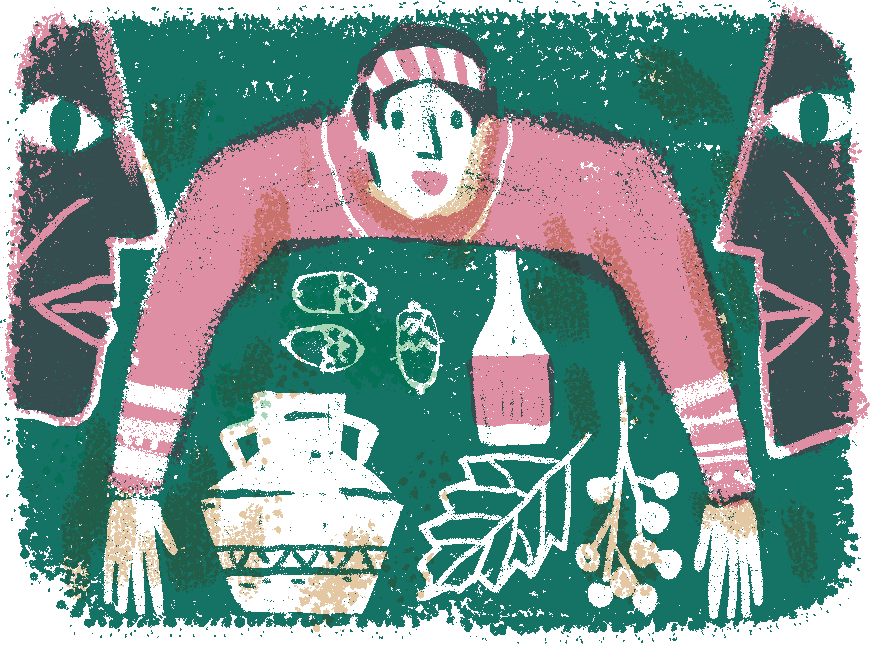

Communicating with Spirits

Step 1.

By chanting, dancing, and with the help of sacred objects, the shaman gets to see the “thread” or “path” that connects to the spirits, and thereby establishes a link to them.

Step 2.

When the connection is established, the shaman will enter a trance-like state and begin to tremble uncontrollably. He/she is believed to be possessed by the spirits as their medium to communicate messages, instructions, and display spiritual power.

Step 3.

At the end of the ritual, the shaman will chant scriptures or dance to send off the spirits. He/she usually feels exhausted after regaining consciousness and therefore needs to take a good rest. The commissioning clansmen or community leader would reward the shaman with gifts or money to thank him/her for their help and hard work.

Declining Shaman Culture in a Time of Modernity

As the heart and soul of animism, shamans not only shoulder the responsibility of communicating between humans and spirits, but also serve to pass on the collective memories and wisdom of indigenous communities. However, due to the advance of modern civilization and the introduction of foreign religions, community members have gradually lost their faith in shaman’s spiritual abilities, and various indigenous peoples are all confronted with the problems of the aging of shamans and lack of successors.

Typically, a shaman is in charge of hosting traditional rituals and the main rites of passage for the community. As times change, they also conduct ceremonies for blessings in terms of public affairs, such as the completion of new roads and bridges. This year, with the world being severely hit by the contagious coronavirus outbreak, some Taitung-based Bunun shamans even display compassion that knows no borders to hold a plaguedispelling ceremony praying for the well-being of mankind throughout the world.

The decline of shamans implies the discontinuation of indigenous cultural transmission. To save the precious shaman culture from vanishing, many indigenous communities have worked proactively to establish cultural associations, community schools, and shaman workshops as a means to revitalize shamanic practices and preserve the knowledge of rituals.

Reference:

胡台麗、劉璧榛,《台灣原住民巫師與儀式展演》,臺北,中央研究院民族學研究所,2010年。

高明文,〈巫師靈力的消逝與重現:從個人經驗與屏東縣文化信仰復興協會說起〉,臺東,國立臺東大學公共與文化事務南島文化研究碩士班,2018年。

章明哲,〈東台灣布農族巫師祭登場 祈福盼度過疫情〉,https://news.pts.org.tw/article/471644,公視網路新聞,2020年3月24日。

李修慧,〈排灣族現代女巫的「成巫之路」:神靈附體完還得去看醫生〉,https://www.thenewslens.com/article/90951,關鍵評論網,2018年4月17日。

李宜澤,〈從靈路上看到多重風景:反思《不得不上路》的詮釋視角〉,https://www.thenewslens.com/article/81228,關鍵評論網,2017年10月21日。

我是小編,〈世界母語日到南投,聽番婆鬼的話,說她們的鬼故事 〉, https://www.matataiwan.com/2014/02/21/kaxabu-wizard-story/,MATA.TAIWAN,2014年02月21日。