If you think“John Doe” can be a placeholder for any type of name, think again! Indigenous naming practices are not as straightforward. Surnames do not exist in indigenous society. In fact, indigenous names usually have a unique structure that can help people identify lineage and avoid intermarrying!

Patronyms

given name + father’s name

Given names are usually passed down from ancestors and adopted by posterity. People often choose the names of the great, the brave, or the virtuous. However, one’s given name cannot be the same as one’s parents or siblings.

A baby may be renamed if the family’s fortune takes a downturn after naming, or if misfortune befalls someone of the same name.

Indigenous peoples that adopt this convention: Atayal, Saysiyat, Kavalan, Truku, Sediq

Matronyms

given name + mother’s name

Men must avoid sharing names with one's father, uncle, or brothers and women must avoid sharing names with one’s mother or sisters. The same convention of changing names to improve fortunes also applies.

In matrilineal societies, it is the eldest or youngest daughter that is entitled to inheritance. In some rare cases, a daughter will take her mother’s name and the son will take the father’s name due to the exclusion of men in a matrilineal society.

Indigenous peoples that adopt this convention: Pangcah, Sakizaya

Call Me by My Grandparent's Name

given name + clan name

The whole family tree can be mapped with this kind of naming practice! For Bunun people in particular, the eldest grandson takes the name of the grandfather, the second-ranking grandson takes the name of the great-grandfather, the third-ranking grandson takes the name of the grand uncle, and so on. This kind of naming practice reveals a lot about the family genealogy.

For the Tsou, Thao, Hla'alua, and Kanakanavu peoples, boys take the name of their grandfathers and girls take the name of their grandmothers. The Kanakanavu peoples have a special genealogical name catalog and they rarely have the same name as others. This makes it easy to tell whether a person is of Kanakanavu heritage just by their name!

Indigenous peoples that adopt this convention: Bunun, Tsou, Thao, Hla’alua, Kanakanavu

Call Me By the Name of My Home

given name + house name

In Paiwan and Rukai societies, each house has a unique name that will change with such circumstances as the family status changing, relocations, or marrying into the wife’s family. A given name is chosen based on a person’s rank and gender. Families that attach greater importance to marrying a family of equal status and rank can thus determine whether a prospect is suitable just by looking at their name.

For Pinuyumayan people, the name of a person’s former family house can still be used, even when that person marries and forms a new family. Pinuyumayan people are often named after their grandparents, or after certain events or objects.

Indigenous peoples that adopt this convention: Paiwan, Rukai, Pinuyumayan

Paedonyms

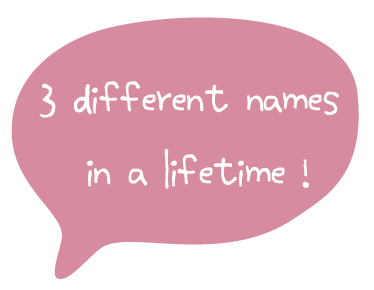

Unlike any other indigenous peoples, the Tao people have a completely different system where the names of parents and grandparents change along with the birth of the firstborn.

In Tao society, the naming practice for the firstborn is “Si + given name”. When the firstborn arrives, the father’s name will change to “Si aman + firstborn’s name”, the mother's to “Si nan + firstborn’s name”, and the grandparent’s names will change to “Si apen + firstborn’s name”. And so, from the changes to a person’s name over a lifetime in Tao society, you will be able to deduce the names of the entire family!

Indigenous peoples that adopt this convention: Tao

How We Lost Our Names

In the 2020 MLB Spring Training games, Kungkuan Giljegiljaw delivered the first RBI for the Cleveland Indians. This talk of the town among American baseball fans is Chu Li-Jen, who hails from Taiwan and has Paiwan heritage. The Cleveland Indians signed Chu Li-Jen in 2012 and this year, he is finally wearing a baseball jersey that bears his indigenous name.

In fact, indigenous people can be seen participating in many sports both at home and abroad. The Chinese names of these players roll right off the tongue of spectators, and yet they often know nothing about these players’ real names. Why don’t indigenous people use their own names? The reason for this can be traced back to Taiwan's history of foreign rule when indigenous peoples were forced to abandon their names for ease of management.

Qing Rule

Chinese Surnames for All

Many Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples intermarried with non-indigenous peoples during the Kingdom of Tungning period through to the era of Qing dynasty rule in Taiwan. Non-indigenous people place great emphasis on bloodlines and lineage and a surname serves as an important indicator of that. Therefore, Chinese surnames were “bestowed” upon any willing indigenous people to indicate the “native’s” submission.

Due to mountain bans in effect at the time in Taiwan, non-indigenous people had scarce contact with indigenous peoples in mountain areas and thus, it was mostly Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples who changed their names.

Japanese Rule

Switching to Japanese Names to Fight Alongside Japan

During Japan’s colonization of Taiwan, the Japanese established a comprehensive household registration system. The Kominka Movement (Japanization) around the 1940s further aimed to fully assimilate the Taiwanese. In an effort to strengthen identification with Japan, a name change program was introduced to encourage Taiwanese to replace their Chinese names with Japanese ones.

In addition to Japan’s aboriginal policies, the Japanese government also went into indigenous communities to recruit young people to join the Takasago Volunteers during World War II. The Japanese language training that indigenous people received and changing of indigenous names into Japanese names were all aimed at strengthening indigenous identification with Japan in both spirit and form and increasing indigenous morale to fight for Japan on the battlegrounds.

The Nationalist Government in Taiwan

Non-indigenous Chinese Names Mandatory for All

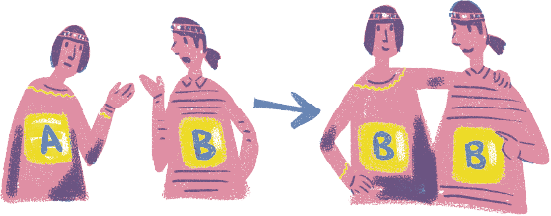

After Japan’s surrender and the Nationalist Government’s takeover of Taiwan in 1945, the government announced an act on the restoration of former names for the people of Taiwan province in 1946. The act required Taiwanese to restore their former Chinese names within three months and Chinese names were forced upon those who did not have one. The household registration authority at the time handed out Chinese names to indigenous people at random using Chinese language dictionaries.

This callous assignment of names created chaos for indigenous peoples who have their own naming practices and led to members of the same clan having different Chinese surnames. Rank and familial relations could no longer be discerned by indigenous names after switching to Chinese names, which not only impacted indigenous identity but also had a detrimental effect on ethics of families.

Ch-Ch-Changes

to My Name

Many indigenous peoples had differing surnames even among members of the immediate family and relatives, which led to ethical problems and family issues. So in 1972, the Taiwan Provincial Government established the Guidelines on Surname and Parent's Name Rectification for Mountain folks of Mountain Indigenous Townships in Taiwan Province. It was specified that if the following two conditions were met, then a person could change their Chinese surname.

1. A person who ought to share a surname with another family member but does not.

2. The surname used is uncommon in non-indigenous society.

In the 1980s, indigenous issues were gradually brought to the fore with Taiwan’s democratic progress. In 1984, the Taiwan Indigenous Rights Advocacy Group (now disbanded) called for the term “mountain folks” to be amended into “indigenous peoples” to eliminate bias and prejudice against indigenous peoples in society.

Since indigenous peoples’ appeal for name rectification came to light in 1984, there have been countless protest movements organized by indigenous legislators, students, non-profits, and social movement organizations. In 1994, additional articles to the Constitution passed the third reading and the term “mountain folks” was officially rectified to “indigenous peoples”. One year later, the Legislative Yuan passed amendments to the Name Act, allowing indigenous peoples to resume using their traditional names; however, their traditional names still had to be indicated in Chinese characters on ID cards.

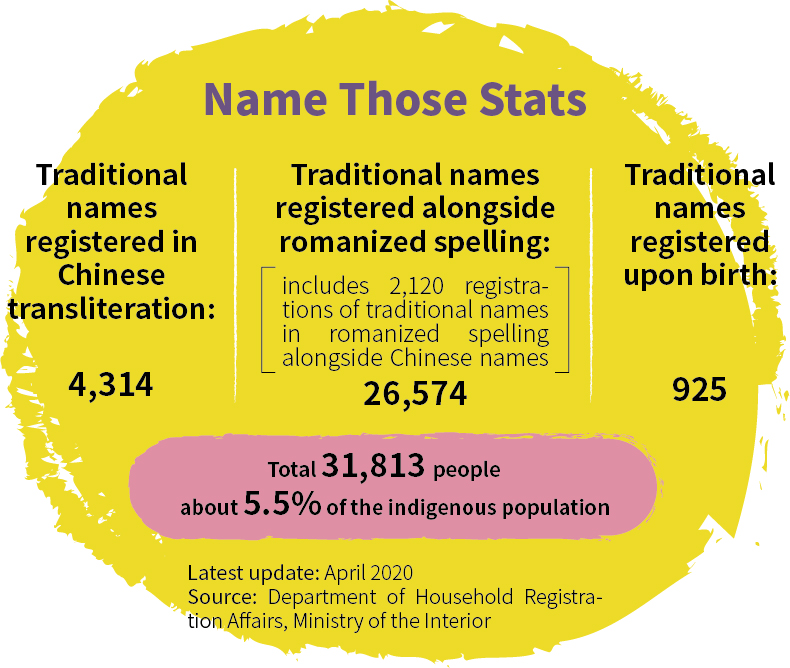

In 2001, The Presidential Office promulgated the Status Act for Indigenous Peoples and in that same year, the government stipulated that traditional names could be registered alongside romanized spelling of the names.?In 2003, the Legislative Yuan once again amended the Name Act to allow the registration of traditional names and Chinese names alongside romanized spelling of traditional names.

To commemorate the rectification of the term used to refer to indigenous peoples on August 1st, 1994, the government designated August 1st as Indigenous Peoples Day in 2005 in an effort to highlight Taiwan’s cultural diversity and ethnic equality.

To commemorate the rectification of the term used to refer to indigenous peoples on August 1st, 1994, the government designated August 1st as Indigenous Peoples Day in 2005 in an effort to highlight Taiwan’s cultural diversity and ethnic equality.

A Name Irretrievable

After centuries of change and decades of effort, indigenous peoples have finally been recognized by the nation and can claim ownership of their names. And yet, 25 years after giving the green light to register traditional names, actual registration numbers remain low. Just how difficult is it for indigenous peoples to reclaim their names?

Lack of Consideration for Indigenous Naming Practices

Indigenous naming practices are not so straightforward as a surname plus a given name. Many indigenous names repeat themselves and some can be quite the mouthful. Even with the increase to 20 characters as the limit for name registrations, it is still not enough to contain certain indigenous names sometimes.

Is Chinese Transliteration Really Better?

In the beginning, the government required indigenous peoples to register their names by using Chinese transliteration. However, Chinese pronunciation does not accurately represent indigenous names and each indigenous peoples have different ways of romanizing names. All of this contributes toward lackluster efforts to register traditional names by indigenous peoples.

A Distant Culture

Due to the rapid disappearance of tradition and culture, many young indigenous people are strangers to their true indigenous names and worry that they will use it wrong or pick the wrong name. Many are also already used to using Chinese names and the changing of a name is not without its effects on daily life. What’s more, lack of awareness among employees at local government agencies also lead to breakdowns in communication and reduce indigenous people's willingness to register their traditional names.

References:

田哲益(2003)| 台灣原住民生命禮俗。臺北市:武陵出版有限股份公司。

鐘聖雄(2017)| 你的名字。鏡週刊,https://www.mirrormedia.mg/projects/real-name/index.html。

南島觀史-福爾摩沙Formosa,https://www.facebook.com/AustronesiaFormosa/。