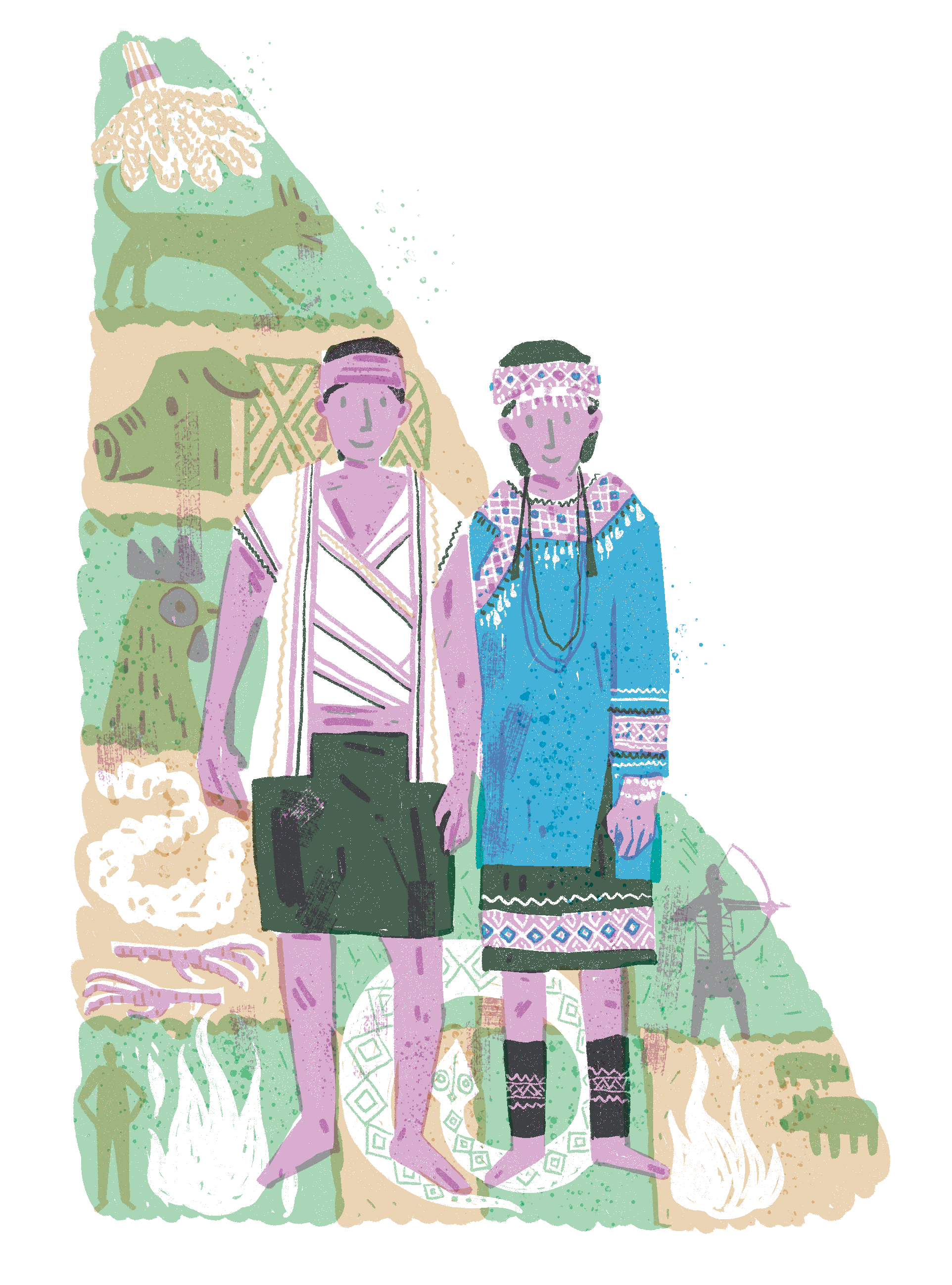

Taboos in Taiwanese indigenous mythology and oral literature are originated from the visions happening in ancestors’ lives. In the awe of nature or the fears of spirits, taboos play a role of unseen restriction and religious prohibition within indigenous society.

The taboos derived from myths and legends have been passed on from generation to generation to shape the principles of behaviour, as well as cultural characteristics. Thus, the formations of these social norms are hidden in the texts of myths – they are embodied in tangible material culture and intangible cultural rituals, constructing the sacred order between heaven, earth, and human.

Home of Flying Fish

Black Wing Flying Fish and Island of Men

The Kuroshio Current (Black Tide) between February to March brings the rich amount of migratory flying fish to the North, signaling the start of fishing season for the Tao people – the indigenous peoples of the Island of Men (Lanyu). The Tao annually held Mivanuwa, a ceremony in which they launched a big boat for 10 people out to sea to announce the beginning of the flying fish festival, which would last through September. During this period, law-like taboos demonstrated their controlling power to regulate the Tao people’s external behaviours and internal thoughts.

Do not catch any fish species other than flying fish; set nets are prohibited; do not catch shrimps on rock reef at night; do not cross others’ house corridors in certain dates, fishing on others’ boats are prohibited, do not come across anyone during fishing, no items exchange, women can’t touch men’s fishing gears, pregnant women can’t visit friends. These noes and prohibitions of food, clothing, housing and transportation are based on the myth in between Tao ancestors and flying fish.

One day, a group of Tao people went to the coast for shellfish and shrimps. Suddenly two fish with wings hiding in the gap of reef rock were found. These people successfully caught one but the other fish jumped out of the gap flying to the ocean. Showing around this fish with wings happily, they cooked it with shrimps and shellfish and shared the meal with villagers. A few days after, the villagers either had skin ulcer or went ill incurably. Meanwhile, flying fish were suffering fatal disease problems. Black wing, the flying fish’s leader, recruited other species of flying fish to discuss what caused plague. The leader eventually found out the reason while the runaway one said that the human on the island cooked them with crustacean.

(Syaman Rapongan, Yatsushiro-wan Mythology , 1992)

...

...

Black wing appeared in an old man's dream , asking him to meet up with other fish besides the rock reef next morning after breakfast. The leader introduced various edible methods and associated restrictions of different fish such as which ones are for elders and which ones are for children: Black wing flying fish, the nobles in flying fish species due to the rarity, can't be grilled by fire and can only be net fished by fire in the evening and boat fished in the daytime. Red wing flying fish, which are the largest amount in the species, can only be fished by livestock's blood sacrifice. White wing species can only be net fished by fire at night and cannot be boat fished in the daytime. Glider Flying fish cannot be eaten by pregnant women. Smaller-sized Kakalaw are for suitable children and don't need to be sun-dried. Loklok, baits for dolphin fish, can be eaten by elders but not for children. Sanisi are also baits for dolphin fish but can't be human food. These handed-down edible methods from generation to generation are now categorised into “fish for men”, “fish for women”, and “fish for elders”.

Indeed, the mythological black wing also precisely notified the ancestral Tao the monthly must-do routines, rules, rituals, taboos, fish boat organising, fish gear and boat fixing, and how-to guideline for ceremonial offerings (taro, millet and livestock). What continued in this myth was that the ancestral Tao people followed all of black wing leader's guidelines and held the first praying ritual next year. This major foundations of Tao’s social life is the typical mythology-supported taboo system and also the sample of a people's sacred orders.

Mice Love Millet

Mythology Interpretation and Ceremonial Praying Before Harvesting Millet

Taiwanese indigenous people's farming patterns vary from community to community but commonly correspond to related myths to connect with rituals and taboos. Thus, the process of obedience from rituals and taboos is a way to understand the interrelation between communities and nature. For Taiwanese indigenous peoples, the most divine grain is millet, and it’s also the most important ceremonial offering in communities’ traditional rituals. There are mainly many taboos to follow during seeding, sowing, and harvesting. There's one Bunun story bringing out with their beginning of agricultural offering and taboo:

One day, a woman was so lazy to break each millet into half and remove bran that she directly put a bunch of millet into pot to cook. Unexpectedly, the millet multiplied rapidly and started popping out from the pot. By the time the house was filled with millet, woman suddenly aware that her kid was s till in the room. The kid couldn't escape from the growing millet and then was forced to turn himself into a mouse. After the mouse got out from the house, “I’ll come back to steal all of your food.” the mouse said to the woman. This kid’s name was Haisul, and this is how Bunun people call the wild mice. After this, Bunun can no longer cook a big pot of meal by a half millet but need to work harder than before for feeding themselves.

(Chen-Yu,Wu, Bunun: Legends and Their Early Customs , 1995)

...

...

Since the woman disobeyed the process, the fulfilling good old day has gone and people need to put more efforts in work. In this case, the related rituals and taboos appeared in life.

If you see the millet float towards you or a snake suddenly show up, the millet must be harvested on the next day. Violating taboos will cause bad luck. For example, insisting to harvest millet on the wrong day regardless the taboos, this family will live in poverty or hunger. Besides, once everybody arrives the millet field, the elders will start some simple rituals. Firstly, the elders have to take a turn round the field and saying the blessing words for family, and also hand cut the grass in order to scare the bad things (snakes and mice) off. Normally, the harvested millet should be passed from right to left. The harvest workers will violate the taboos if they take the wrong turn.

(Yo-Shui Fang,Li-Min Yin , Bunun , 1995)

...

...

The regulated rituals and taboos in each season's millet works present the Bunun people's dependence on crops. The reasons why the Bunun avoid to see mice and snakes before harvesting millet are because that mice cause harms for grain, and snakes is the symbol of massive water flooding and mysterious horror in ancient mythology. Many indigenous communities believe that snakes belong to god of mountain and the appearance of snakes is the omen of prohibition from god of mountain.Thus, the indigenous people will never continue any move of hunting, journey or headhunting once they see the snakes, just like the ominous sign of augury.

The Past is Not Far Away

Origins, Wayfinding, and Coexistence with Nature

Early Atayal community inhabited around Ren Ai Township in Nantou County but gradually expanded their territory due to cope with the growth of population. It's said that when Atayal people tramped over the north peak of Nanhu Mountain, overlooking northward and eastward, they found an abundant land perfect for living in between Lanyu River and Heping North River. Thus, the Aatayal people divided into several groups to migrate. One of the groups headed down to the east near upper reaches of Zhuoshui River to build Tpiyahan Village as their first relocation and the branches of this group continued eastbound to follow Nan'ao South/North River and Heping River basin to settle down the villages one by one all the way to the final destination: Da-Nan'ao Plain, where its southern coastline fronts onto the sea. An Investigation of the Customs of the Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan,Vol.1 / Atayal recorded the migration route of Atayal people:

In the ancient time, there’s a big rock with one man and woman inside up on Papak Waqa (Dabajian Mountain). When two birds, the crow and Siliq knew it, they visited there everyday to pray the birth of human being. One day, Siliq’s pray was finally answered. This big rock cracked into half and the man and woman showed up. These two human beings got married and had their own child. Hundred years after, their descendants are called Atayal people nowadays.

(Chi-Hui Huang, An Investigation of the Customs of the Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan,Vol.1 / Atayal,1996)

...

...

Pan-Atayal's life began from cracked stone as recorded in ancient mythology. Even though the territory were gradually expanded and population grew more and more, the stories keep reminding their people where they were originally from: Dabajian Mountain and Rueiyan.

One of the essential figure in Atayal mythology is Siliq, a gray-cheeked fulvetta with magic power. Everything happening in the community needs to be decided by Siliq's chirp or flying direction. According to the myth, Siliq used to had a competition with the crow to see which one could remove the stone that blocked the river and the road. None of human and crow could push it away. However, Siliq flew onto the stone, jumping up and down several times. Siliq succeeded. The landslide dam came back to life again. Some myths claimed that after Siliq pushed the big stone into water, a man and a woman, the Atayal ancestors, appeared from the cracked stone. Thus, Atayal people see Siliq as a divination bird with god's power. Before Atayal warriors went headhunting or regular hunting, the community would ask Siliq's divination first.

In fact, indigenous people's early life revolved around natural environment and had very close relationship with the earth. Hunting and farming are their major ways to make a living. In this case, hunting plays an extremely role in Atayal life. They have very strong sense of territoriality and strictly followed the hunting rules and taboos such as, keeping a good mood before departure, joking or swearing are strongly prohibited while placing the traps, and respecting the hunted animals. Besides, if you meet some other people on your way back from hunting, you need to share some of your prey with them as a blessing. Sharing with others is an important tradition of Taiwanese indigenous peoples.

Apart from hunting, natural vegetables, fruits, fish and shrimps are all the important food sources. And bamboos, tree vines and woods can be used for house building and living appliance. All the lives from mother nature have their own values and the wisdom of life are shown in these details.

The origin and myths of Pan-Atayal reminds their posterity of human-earth interaction and the connection of communities through their migrational routes. And how Atayal people harmonise the peace and balance with nature can be found from their divinations, which clearly reveal the sense of coexistence.

Reappearance of Rituals and Taboos

Possibility of Culture Revival

Faith assists human beings to built the world; mythology reveal the origins of necessary matters to signify the relationship between human and nature; taboos are the influential norms to integrate the society to support every race's core value of life. After the clashes brought by Taiwanese mainstream social value and modern regulation systems, indigenous people's mythology, rituals and taboos are differently presented in history and culture at the point of fading away or being wiped out.

From the past new years, each people's rituals and traditions can be found remained and even solider whether it’s because of the official power or communities' efforts. The culture value and inheritance are highly emphasised nowadays after the combination between faith and modern regulations. The reappearance of rituals can be expected to be the tool of social cohesion and community rebuilding through the costumes, hunting gear, faming tools, houses, taboos or mythology. The comeback of “Sea Festival” by Kavalan people, developed “Night Festival” by Siraya people, and the reappearance ritual of objects(copper bell and belt accessory) uncovering by Amis people can be seen as the role models of ritual-oriented culture revivals.

For a long time, what support a people is the vision of universe as the collective faith, or in another word, an empowered taboo system. In fact, this inner power not only just shape the past, but precisely become the centre of the rebuilt ones.

- Reference -

李亦園,《臺灣土著民族的社會與文化》,臺北,聯經出版,1982。

巴蘇亞˙博伊哲努(浦忠成),《臺灣原住民的口傳文學》,臺北,常民文化,1996。

巴蘇亞˙博伊哲努(浦忠成),《原住民的神話與文學》,臺北,臺原出版,1999。

夏曼.藍波安,《八代灣的神話》,臺北,聯經出版,1992。

田哲益,《泰雅族神話與傳說》,臺中,晨星出版,2002。

田哲益,《布農族神話與傳說》,臺中,晨星出版,2003。

王嵩山,《台灣原住民:人族的文化旅程》,臺北,遠足出版,2010。