The indigenous peoples in Taiwan did not have written languages of their own.Through word of mouth was the only way they could save the mythologies told by their ancestors.

Not until a British, George Taylor, published the stories, which he collected, about Taiwanese indigenous people in English in 1887, did the use of text to record indigenous mythology in Taiwan mark its renaissance.

Since the focus of development under the rule of Dutch colonists and Koxinga was solely on Today's Tainan area, as a result there was insufficient understanding of Taiwan as a whole. Later on, though Taiwan was controlled by the Qing government for more than 200 years, the government's attitude towards Taiwan was quite passive. The government even implemented ethnic segregation policies between Han people and highland indigenous people. Borders between the Chinese-controlled area and the indigenous regions were indicated by ditches known as earth cows or red lines in order to prevent the two sides coming into contact, which was a form of “one side, one country” and “one country, two systems.”

The earliest record of indigenous people in the reign of Cing Dynasty was kept in local chronicles. However, those records were mostly past evidence reorganised and copied by local officials or intellectuals sitting in the office. They seldom conducted field studies. In other words, the description about indigenous people in these local chronicles is simply plagiarism. No detailed accounts of each people's mythical stories and legends could be found. After 1860, Taiwan opened its ports for trade attracting international trade and visitors from abroad. In 1887, George Taylor, who managed the lighthouse in Eluanbi, Pingtung, released articles about the mythologies and legends of Taiwanese indigenous people, which he had collected, from an international point of view, serving as a prelude to the writing down of oral folk tales of indigenous people in Taiwan.

Full-scale Gathering of Evidence by Japanese Scholars

Rich Historical Materials about Indigenous People

During the Japanese occupation, the Japanese government carried out very thorough anthropological field work for the convenience of colonisation. The Japanese scholars left their footprints in almost every corner of Taiwan with the furthest to the Orchid Island where they made a long-term investigation. They recorded myriad data on indigenous peoples and mythical stories and legends of each people. This had been the first systematic and complete record on indigenous peoples.

Around Taisho period (1912-1926), Sayama Yukichi, who had produced fruitful written reports about indigenous people mythology, released “Report on The Barbarian Peoples,” which dedicates a chapter to the legends and mythologies of indigenous peoples. In 1923, he and Onishi Yoshihisa also published “A Collection of Savage Myths and Legends,” which puts indigenous myths and legends into categories ranging from creation stories, the origin of oral history, and the creation of traditions and customs.

Then approximately in 1931 during Showa period (1926-1989), Ogawa Naoyoshi and Erin Asai based their research on the investigation into indigenous people mother tongue and completed “The Myths and Traditions of the Formosan Native Tribes.” The stories narrated in Takasogo-zoku languages (the generic term used by Japanese for highland indigenous people) were converted by using International Phonetic Alphabets (IPA) symbols. The book was published by Tokyo Toko-shoin in 1935. Since its publication, the book has served as important reference for research on myths and legends of Taiwanese indigenous peoples. The post-war writer, Chen Cian-wu, even translated the book and published “The Myths and Traditions in Native Languages of Taiwanese Indigenous People” in which the mythologies of each people were categorised and organised so as to help readers get to know the mother tongues and culture of indigenous peoples.

Others like the “Report on Barbarian's Customs” by Kojima Yoshimichi and “The Formosan Native Tribes: A Genealogical and Classificatory Study” by Utsurikawa Nenozo also touched upon the folk tales of indigenous people.

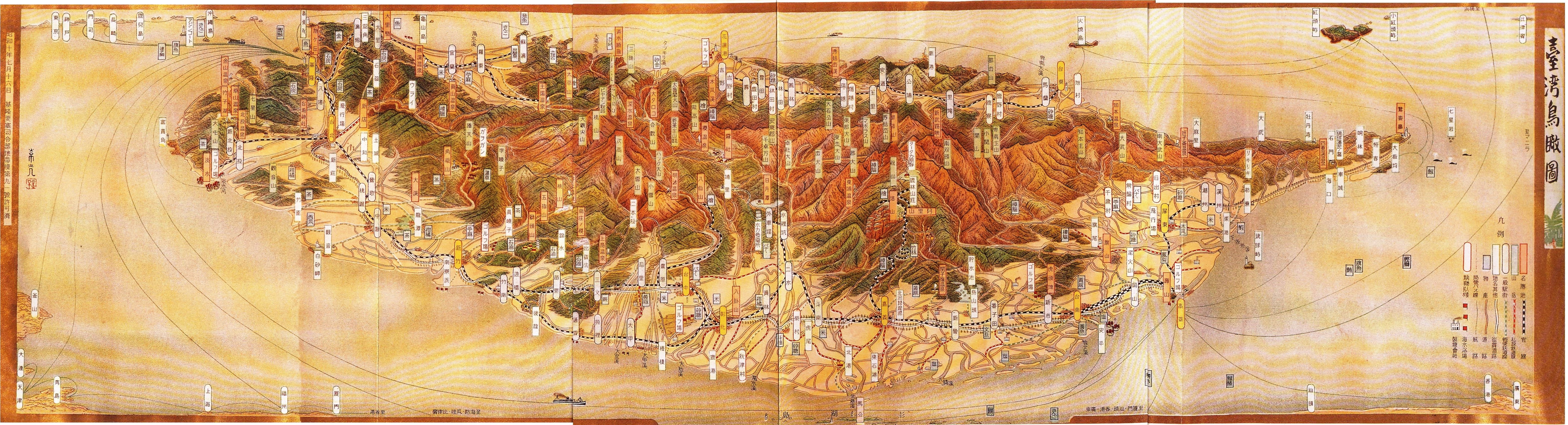

1935臺灣鳥瞰圖 Aerial View Map of TAIWAN-FORMOSA 1935

(https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:1935%E5%B9%B4%E8%87%BA%E7%81%A3%E9%B3%A5%E7%9E%B0%E5%9C%96_Aerial_View_Map_of_TAIWAN-FORMOSA.jpg)

Writing One's Own History

After the second World War, people continued to write about indigenous people mythologies with some scattering in local chronicles and others presented in specialist publications. At this point in time, quite a number of indigenous peopleintellectuals devoted themselves to the writing, preservation, and interpretation of myths thanks to the love and care for their own culture. Since the 1990s, the Taiwan Historica of Academia Historica had set out to compile, edit, and publish “The History of Taiwan Indigenous People,” a series of introduction to the history of different indigenous communities. In the editing process, experts, scholars, and indigenous people intellectuals compiled history of each community based on oral narratives of old sages, field studies, and data collection. This series published by Academia Historica has been considered an important reference book for research on historical materials or mythology of indigenous people. It is literally the encyclopaedia of post-war indigenous people.

In addition, the prevalence of education among indigenous peoples urged indigenous intellectuals to reflect on the value of their culture. In order to preserve their culture, they dedicated their efforts in the study of materials about their history and the writing of oral narratives. Through these indigenous authors and scholars, a more in-depth and authentic analysis on the indigenous myths and legends could be produced. Tasi-ulauan Pima (Tian Jhe-yi as his Chinese name) of Bunun people compiled and edited a series of books entitled “A Collection of the Indigenous Myths” in the form of one book for one people to discuss and introduce in detail the mythological system and expressions in each people. He further divided the mythical stories into the creation of the world, origin of the earliest ancestors, the Flood, taboos and diet, etc. Nevertheless, this series of books were published in 2003 and only included 10 peoples, which were recognised by the then authorities.

The incumbent Vice President of the Control Yuan, Mr. Sun Ta-chuan, who is also a Bunun, planned and published “A History of Taiwan in Comics” with 10 volumes for the 10 peoples mentioned above. This series introduces the mythical stories and legends of indigenous people. He is also the author of “The World of Mountains and The Sea: The Spiritual World of The Indigenous Peoples,” which elaborates on the beauty of indigenous people mythologies.

Mr. Pu Jhong-yong, assuming the role of the Minister without Portfolio at the Examination Yuan, is not only a Tsou, but also a very important indigenous writer. He has assisted Taiwan Historica in completing “The History of Taiwan Indigenous People: Tsou People.” He also published “Oral Literature of Taiwan's Indigenous People,” which focuses on the background for the emergence of indigenous oral literature and its characteristics. On one hand, this book details the indigenous myths and their types and analyses the similarities among different communities in narrating mythologies. On the other hand, it depicts Pu's viewpoints on indigenous oral literature. Examples include why indigenous people do not have written languages, his call for attention to the preservation and education of indigenous oral literature, and so on.

Over the long Span of Time,

Long Live the Indigenous People History.

Up to now, there have been more diversified approaches to write and record indigenous people mythologies including prose, illustrations, picture books, novels, board games, etc. They are very popular with the young generations, and help more people know about the indigenous mythology.

The writing and preservation of indigenous mythology is a long and painstaking process. Each people and each village might have their own version of oral narratives. They might share similarities with neighbouring communities, yet they could also be very different and unique. Just because indigenous oral narratives are diverse and rich in content, one has to understand the features of each people in order to do in-depth analysis. To make things more difficult, indigenous people have a very long history, so even the indigenous scholars still have to pay tremendous efforts in visiting, double-checking, and writing. Hopefully, readers will know more about how the written indigenous people mythology was formed and have a sound understanding of the development of indigenous people literature.

- References -

巴蘇亞˙博伊哲努(浦忠成),《臺灣原住民的口傳文學》,臺北,常民文化,1996。

陳千武譯述,《臺灣原住民的母語傳說》,臺北,臺原出版,1994。

曾建次,《祖靈的腳步:卑南族石生支系口傳史料》臺中,晨星出版,1998。

達西烏拉灣•畢馬(田哲益),《原住民神話大系7:卑南族神話與傳說》,臺中,晨星出版,2003。

孫大川審訂、陳雨嵐著,《台灣的原住民》,臺北,遠足文化,2005。

葉家寧,《臺灣原住民史:布農族史篇》,南投,國史館臺灣文獻館,2002。

許木柱、廖守臣、 吳明義,《臺灣原住民史:泰雅族史篇》,南投,國史館臺灣文獻館,2002。

王嵩山、汪明輝、浦忠成,《臺灣原住民史:鄒族史篇》,南投,國史館臺灣文獻館,2002。

喬宗忞,《臺灣原住民史:魯凱族史篇》,南投,國史館臺灣文獻館,2001。

蔡美雲,〈《台灣原住民的神話與傳說》之研究〉,彰化,國立彰化大學國文系國語文教學碩士班碩士論文,2008