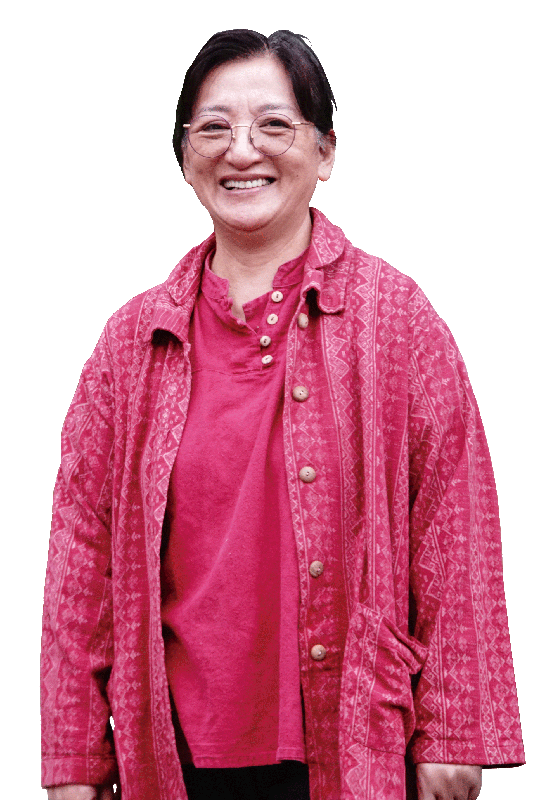

“I would like to bring back the female worldview, so women can be themselves again.”

Throughout her thirty years of indigenous feminist movement, Apu’u Kaaviana tried various ways to help women find their true“self”. From establishing the Women’s Den to offering leather crafting workshop, cultural development workshop, women empowerment workshop, and cultivating the Usuru, women’s farmland.

After the Typhoon Morakot in 2009, the people of the Takanuwa Community returned to their devastated homes. They worked hard at rebuilding their homes while taking to the streets in protest of government’s permanent housing policy. In order to stand guard over their land, women built a simplified grass hut on a vacant lot in the community, and named it To’onnatamu, meaning where the elders are. There they worked actively on preserving food in preparation and prevention of disasters.

During the day, they grew vegetables and kept chickens in the clearing in front of the hut, and looked after the elders and children resting in the hut. During the night, they cooked over the fire and kept each other company. Two or three years went by this way, until one day, a few elders were rather moved when watching Apu’u farming the plot with other women, “seeing you like this is just like seeing the old Usuru.” The sight of women working in the field brought the elders back to when the Usuru, the women’s farmland of the Kanakanavu people, still existed.

In the past, there would always be a plot in the community, growing a mixture of traditional xerophytes, such as millet, turmeric, and taro. When men leave to hunt, the plot would be where women gathered to plant food, preserve crops, and store food. Men would not know how to farm, only women would have possessed such wisdom. Apu’u says, “it wouldn’t matter if men came back empty-handed from the hunt, women would gracefully produce food from the Usuru.”

The typhoon devastated the community, destroyed all financial assets and resources, and traumatized the people irrecoverably. Even though they have returned home, they continue to face fears of disrupted transportation during flood season, and survival crisis such as lack of food supply. “We didn’t used to be afraid of going hungry when we had the Usuru, why are we so afraid of being without food now? Why have we forgotten that we have the Usuru?” asked the elders.

“Women play a vital role in terms of survival. When facing major disasters, the knowledge and wisdom possessed by women can reestablish the normal life, and provide food with stability, but this vital role has vanished in the modern age,” Apu’u lamented, “after the typhoon, everyone’s heart broke, and what we needed to do was to anchor everyone with the Usuru, and rebuild life as we knew it in the community.”

See the Inequality of Indigenous Women

Starting from the Urban “DEN”

The strength supporting the rebuilding of the Takanuwa Community originated from the WOMEN’s DEN, which is the Kaohsiung City Indigenous Women’s Sustainable Development Association established by Apu’u in 2003.

The Takanuwa community is a patrilineal society, and since her young age, Apu’u had sensed the low social status of women in their community. “In 5th grade, a good friend of mine said she was getting married and won’t be coming back to school the next semester.” Still rather young back then, the concept of marriage was unfathomable to Apu’u, who could not understand how marriage had anything to do with them.

For economic reasons, women in the indigenous community often entered workforce early to support the male in the family in pursuing education, or abide by the custom of “marriage exchange” with other Kanakanavu communities, and enter marriage at a young age. After Apu’u got older and left the community, she discovered that in addition to the deep-set gender inequality in the city, there was also discrimination against the indigenous peoples by the Chinese. Once, Apu’u attended a “cultural event” held for “urban aboriginals” in the city, and as soon as she arrived, she frowned. “Indigenous women were dancing in traditional clothing with extremely short skirts while the emcee was yelling in Taiwanese, ‘shake that booty! You aboriginal chicks need to kick higher!’” She recalled. All the “uneasiness” she felt facing gender issues since her young age suddenly resurfaced, and she wondered, “where are the other indigenous women in the city? Are they treated this way as well? What can we do about this together?”

In 1997, Apu’u established the Kaohsiung County Indigenous Women Development Association in Fengshan, hoping to provide a “den” to all indigenous women in the city where they can form a support network. She encouraged blue-collar indigenous women from different ethnic groups to be brave, and tell the stories of their lives. After a long time of companionship and practice, these women finally had the confidence to embrace their indigenous cultures, and became lecturers of indigenous culture and craft in community colleges.

With her successful experience in the city, Apu’u began thinking about how to replicate the pattern of women empowerment in her indigenous community, and help her people break free from the gender stereotype.

Bring WOMEN’s DEN to Community

Encourage Women Participation in Public Affairs

But problems in the indigenous community was a whole different story, Apu’u says, “domestic violence is a serious and complicated problem in the community, but with the intimate interpersonal network in the community, everyone traditionally assumes that the woman is to blame for the domestic violence. A lot of children even grew up watching their mothers subjected to domestic violence and public condemnation, to the point that they were seriously scarred.”

To keep these women company, Apu’u established a Women’s Den in her community, followed by organizing leather crafting workshop and cultural development workshop, so that the women can learn new skills while taking care of their children involved in the cultural development workshop next to them. Teachers in the development workshop are also the same women, teaching children the everyday culture in their community. On the one hand, it helps to nurture the women’s confidence in storytelling, on the other, children get to see their mothers “in a different light”, and rebuild that trust between mothers and children.

Women’s Den hopes to help the women find themselves again, encourage them to actively participate in the public affairs of the community, fight for a chance to go back to school, and even work up the courage to report the domestic violence incidents. Women’s Den was naturally criticized for bringing about these changes, the public believed that women who go to the Women’s Den are “far from decent”, and could easily lead to family dispute, “if you go, you can kiss your marriage goodbye!”

“In a closed community that is dominated by patriarchy, it is extremely challenging to attempt to protect the safety of women.” Apu’u sighs, “people seemed to have forgotten that we were first and foremost human, before we were women.”

Finding Our Way Home

Regaining the Female Worldview

After years of hard work, just when things at the Women’s Den were beginning to run smoothly, Typhoon Morakot came and almost wiped out the entire community. However, this disaster incidentally helped Apu’u and sisters at the Women’s Den reconnect their femininity with the land, the community and the environment, “we want to bring back not only the Usuru farmland, but the female worldview, the knowledge system connecting women to the indigenous community culture.”

How to plant the crops, how to preserve the seeds, how to coexist with the land, and maintain enough food to sustain the community..., all of which are the knowledge and wisdom exclusive to women. But as time went by, everyone forgot what it meant. “If we can take good care of the land, we can bring back the rich ecology we had. That is how we can live a dignified life on our own land,” so says Apu’u.

In the future, Apu'u will continue to lead the sisters of the Women's Den, and find their path in the community and on this land. Apu’u has always believed that only by rediscovering the ecology and culture that is connected to the land, will they be able to reclaim the value and meaning of their roles in the community as women, and really find their way back home – back to their own land, to their own culture and become their true selves.