From Taiwan Indigenous Peoples’ Right Advocacy Association to Thao Cultural Development Association, Panu Lhkapamumu has spent his life fighting for the rights of indigenous peoples in Taiwan. At 60 years old, he is still full of life with eyes gleaming at the mention of indigenous affairs, “I have dedicated my life to indigenous peoples in Taiwan.”

Sun Moon Lake in Nantou County is a popular tourism spot, and the homeland of Thao people for generations. However, the construction of reservoir, enforced expropriation, and readjustment of lands since the Japanese ruling period, has led to the gradual loss of their lands, followed by the loss of ceremony and rituals, language, history, and culture.

Born in 1995, Panu grew up in the Ita Thao Village at Sun Moon Lake, and watched the hometown he was so familiar with slowly changing and disappearing as he got older. Questions and anger rose in Panu, “how can the government just take our lands like that?”

Without Identity,

the Law cannot Protect Us

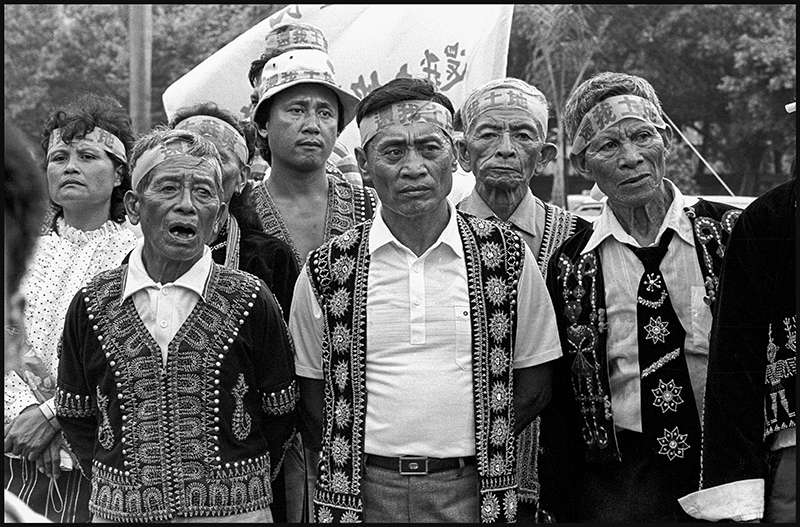

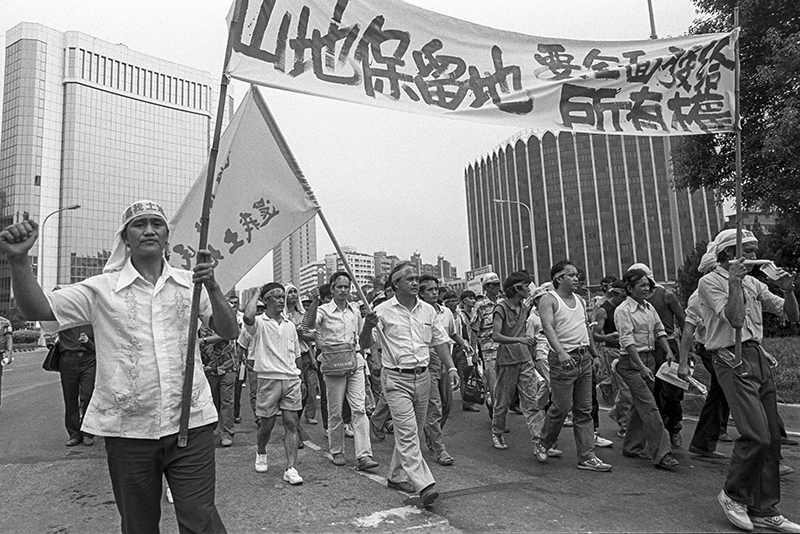

In 1988, in the first Give Back Our Lands Movement launched by Taiwan Indigenous Peoples’ Right Advocacy Association, over 2000 indigenous people from different ethnic groups marched the streets together. This movement awoke the identity of many indigenous peoples, and initiated a series of movements in fighting for indigenous rights.

To bring more indigenous peoples in Taiwan in solidarity, Taiwan Indigenous Peoples’ Right Advocacy Association even traveled to Sun Moon Lake, where the Thao people resided, to recruit like-minded people in joining their cause. Already built a family and business in his homeland, Panu caught on the trend of indigenous movement and joined the Taiwan Indigenous Peoples’ Right Advocacy Association in 1989, taking up a series of positions as director, Vice Chairman, and Chairman.

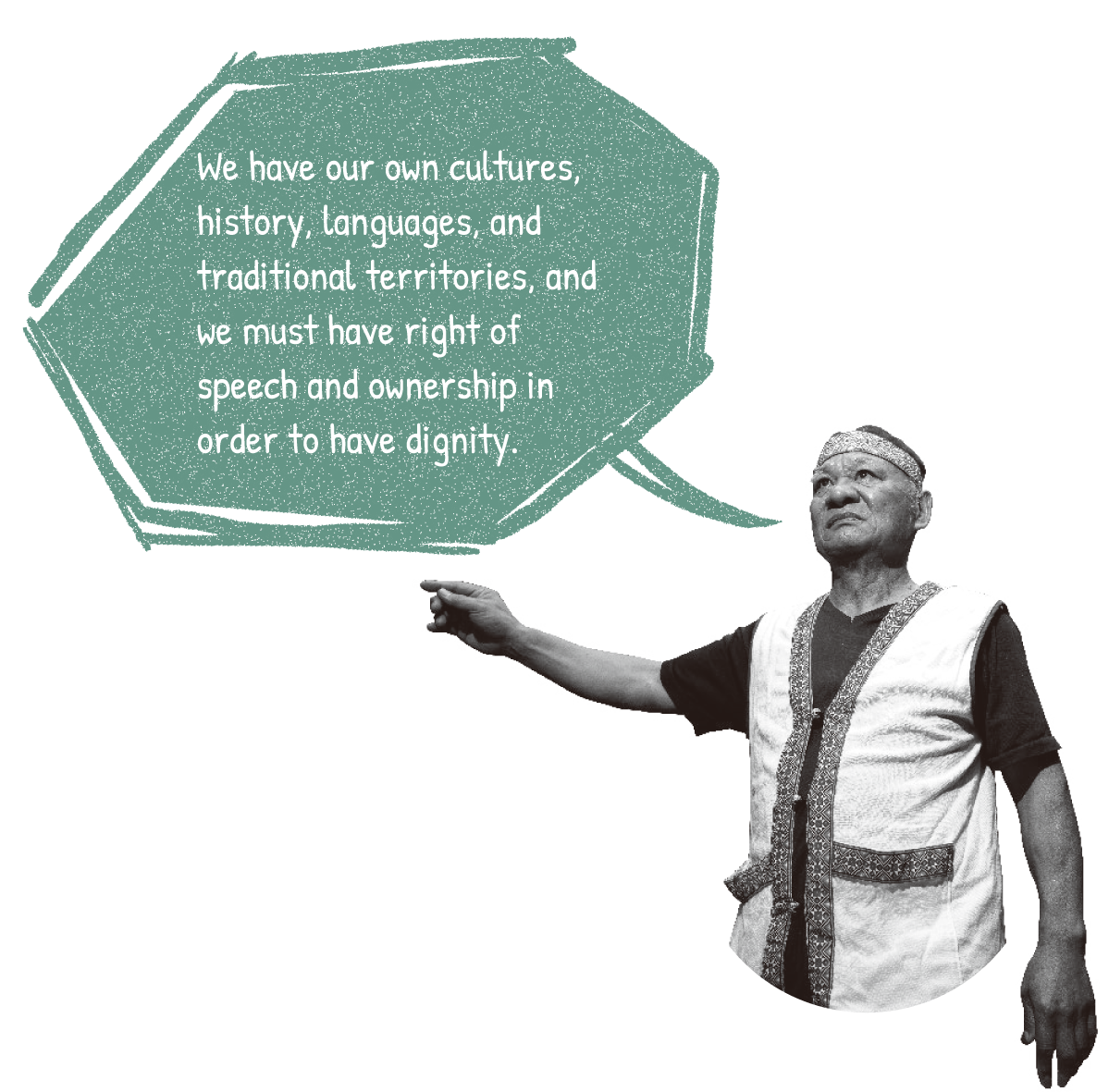

In 1992, Panu took part in the inaugural meeting of Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) as Vice Chairman on behalf of the Association and took up position as the executive commissioner for AIPP Northeast Asia. He realized that whether in Taiwan or Asia, or even the entire world, the fate of indigenous peoples is the same, facing misappropriation of lands, deprivation of rights to survive, and loss of mother languages. Panu sighs, “because we have no legal ‘identity’, the law cannot protect us.”

Representing AIPP, Panu visited the UN the following year and took part in the drafting of the final version of United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The first Article of the Declaration clearly states, “Indigenous peoples have the right to the full enjoyment, as a collective or as individuals, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms as recognized in the Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights law.”

The experience of participating in international organizations enlightened him with the need to establish an association which can contend against the nation, and further firming his determination in the faith to fight for indigenous peoples his whole life. “Not only the mainstream ethnicity deserves human right, but indigenous human rights are also equally important, we should protect the rights of indigenous peoples with law and charter!” says Panu.

1988, indigenous people march in protest, demand that the State return their lands.

Return to My Indigenous Community

to Be with My People

At the end of 1990s, claims made by Taiwan Indigenous Peoples’ Right Advocacy Association have received one after after responses from the government, achieving their interim goals. Some members of the Association went into politics, while others left the various indigenous movements and returned to their own indigenous communities.

Having no interest in politics, Panu returned to Sun Moon Lake to actively promote the revitalization of Thao culture, “the Thao people faces many challenges, I must return to my community to stand with my people.” He set up the Thao Team in 1998 to take part in the project of Write Your Village History launched by the Taiwan Provincial Government, leading his people in combing through the culture and history of their indigenous community, and solidifying their ethnic identity. In 1999, Panu established the Thao Cultural Development Association and became the board director, developing the context for the revitalization of the entire Thao culture.

Less than three months after the establishment of the Association, September 21 earthquake devastated Nantou. The Association quickly organized the Thao Reconstruction Committee to accept donations and disaster relief from Taiwan and abroad and announced the Thao Declaration for the Reconstruction of the Devastated Sun Moon Lake, recruiting Thao people to work instead of simply receiving disaster compensation, build their own houses, push for the name rectification of the Lalu Island, establish the Thao Cultural Park, and advocate for the government to return their old territory. While reconstructing their homeland, Panu worked to create solidarity within the Thao people, inadvertently pushing for the successful name rectification of Thao in 2001, rather than being part of the Tsou people.

This is Our Land;

We Deserve the Basic Right to Consultation and Consent

For many years, the Thao Cultural Development Association has worked on cultural affairs including history and field research, learning traditional rituals, teaching and promoting of mother language, and helping indigenous communities in defending indigenous rights using the modern legal system.

Panu states that it is difficult for traditional indigenous communities to fight against the State. The Association acts as the channel for communication between the Thao people and the government. Once a joint resolution is made by the Thao People’s Assembly, the Association will execute the collective consensus of the ethnic group. Among which, in the lawsuit against Peacock Park Hotel BOT in 2016, not only is Thao rights involved but the issue of indigenous traditional territory right is pushed to the firing line in the fight against state power.

The Peacock Park Hotel was originally set to be located next to the Sun Moon Lake Ring Road, the old path, arable land, as well as ceremonial site for Thao people in the old days. In 1968, Chiang Kai-Shek instructed that a zoo be set up in this spot to keep peacock and other birds, thus the name Peacock Park. In 2016, word got around that Nantou County Government planned to BOT the land to a corporation to build a hotel.

The Thao Cultural Development Association visited the county government back then to understand the reason for this project, but the county government immediately agreed to a public bid for the BOT project after they left. “How can you develop our traditional territory without the consent of Thao people? Are there not enough hotels at Sun Moon Lake?” Panu explains with agitation that they are not only defending the traditional territory of Thao people but protecting the natural environment in Taiwan, “this land belongs to the people, it cannot become the property of a corporation.”

I will Keep Fighting to the End of My Life

Pursuant to Regulations for the Demarcation of Indigenous Land or Land for Indigenous Village, the Thao People’s Assembly demarcated the public land of Yuchi Township as Thao traditional territory, which includes the Peacock Park, in the fight against the county government and corporations, becoming the first ethnic group to announce their traditional territory. But Nantou County Government and Yuchi Township Office appealed to the court to revoke the demarcation of Thao traditional territory. “Indigenous peoples deserve the basic right to consultation and consent! We would rather let peacocks live there than build hotel that would pollute the land,” Panu stresses with firmness.

In the 20 years of his return to the community, Panu spares no effort in participating in public affairs and accumulating the momentum required. He believes that only by obtaining the legal identity and power of self-government will they be able to resist violation against Thao people by corporations, the local government, and even the State. “In the future, we must move towards self-government.”

Along the road of indigenous movement, Panu has always fought on the front line. His hair may be grey, his eyes still sparkle with courageous toughness, “this road has yet to come to an end, I will keep fighting until the end of my life.”