Despite totally blind in both eyes, Malieyafusi Monaneng sees more clearly than anyone the plight of the disadvantaged situation indigenous peoples is in. He aims straight at the center of issues with his poetry, and experienced the turbulent age in the era of indigenous movement by taking part in the establishment of Taiwan Indigenous Peoples’ Right Advocacy Association and convening the indigenous community squad. To this day, he still speaks up for indigenous peoples.

“When the bell chimes again / Mom and dad, do you know? I really hope / that you could give birth to me again.”

The singing resonates inside the Monaneng Massage, booming. Malieyafusi Monaneng, the Paiwan poet, stares straight ahead with sharp eyes. Hard to tell that he is totally blind in both eyes if you had not known ahead.

Poetry is how he speaks to the society. In 1984, Malieyafusi Monaneng and parangalan established the Taiwan Indigenous Peoples’ Right Advocacy Association. He appeals with the poem Restore Our Names, “if one day / we were to stop the wandering on our lands / first, restore our names and dignity.”

In the poem Here, Let’s Drink, Malieyafusi Monaneng criticized the government for not giving indigenous peoples the right to decide the future of Taiwan, “in the slogan of self-determination for 1,800 million people / you hear not our sighs / equality and fraternity, justice and axiom / have long deserted us.” In 1989, The Beautiful Rice, a collection of 30 poems was published. Malieyafusi Monaneng became the first indigenous poet to write in protest for indigenous peoples in Chinese. He was 33 that year.

Suffered Throughout His Life

and Even Harbored Dark Thoughts

65 this year, Malieyafusi Monaneng suffered tremendously his entire life. Growing up poor, his mother died from tuberculosis when he was barely 6. In middle school, his father was sentenced to jail for logging, and as the oldest son, he became the bread winner. But his younger brother was taken away as child laborer before turning 13, and his younger sister tricked into child prostitution.

Graduating from middle school, Malieyafusi Monaneng passed the exam for Air Force Mechanical School (now known as Air Force Institute of Technology) but discovered that he had retinitis pigmentosa during the physical examination and that he would eventually lose his eyesight. Unable to enroll in the air force school, he instead took up work in Taipei. He did everything he could in order to survive, from sandstone, bundling to porter. He even washed carcasses.

Surviving in the non-indigenous society meant that discriminatory vocabulary including “mountain people” and “barbarian” followed him everywhere. Malieyafusi Monaneng just wanted to make an honest living, but he was repeatedly scammed by employment agencies, “took my ID and sold me wherever they pleased, they were all liars!” He swore to himself that, “one day I will grab a katana and slaughter all of you.” He never put the thought into action, but a few years later, Tang Ying-Shen did exactly what he had in mind. Malieyafusi Monaneng once said that if he had not moved into indigenous movements and found a place to speak and vent, he could very well have become the second Tang Ying-Shen. Truthfully reflecting the sorrow of indigenous peoples being at the bottom of the society.

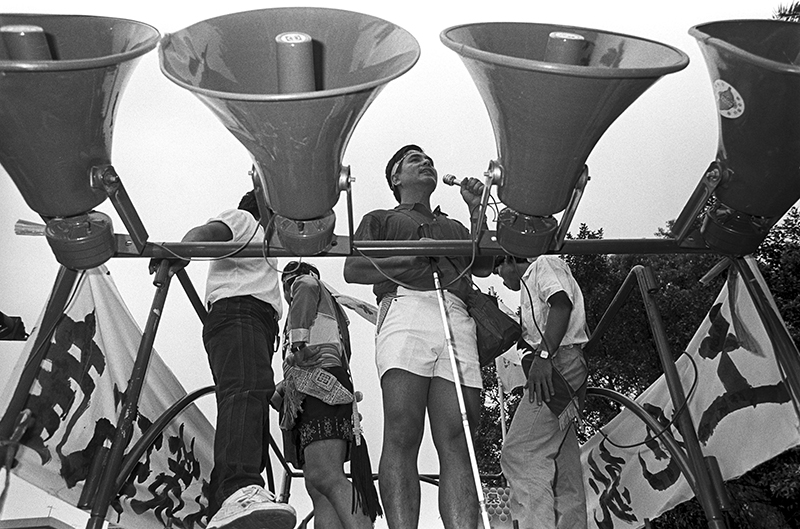

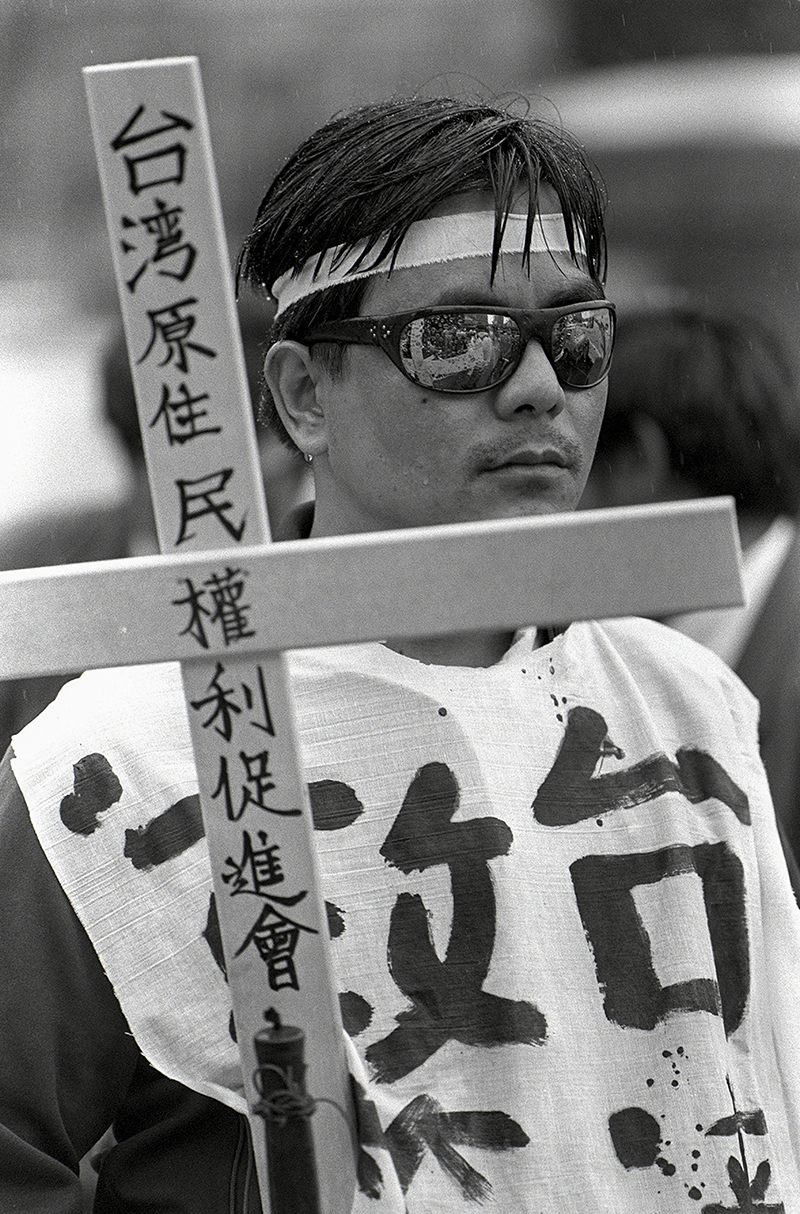

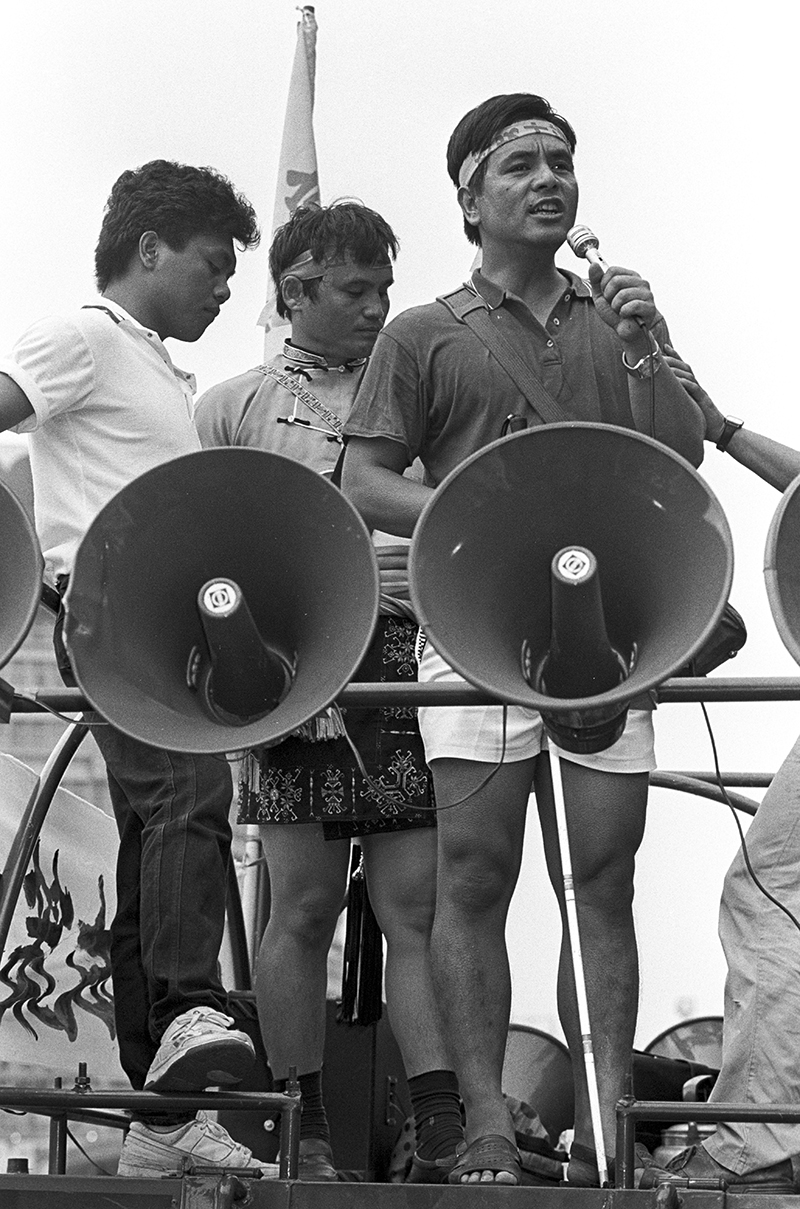

April 13, 1987, indigenous groups protested at the Executive Yuan against Tongpu grave-digging, Malieyafusi Monaneng carrying a crucifix.

Remaining Optimistic

Despite the Experiences at a Young Age!

Malieyafusi Monaneng acquainted undergraduate students providing indigenous community services and the teacher Wang Jin-Ping upon a visit back to his village, which led him to befriending many non-indigenous people, most of which are political activists. When he was 22, Wang Jin-Ping invited him to assist Chen Gu-Ying and Chen Wan-Chen in their election campaigns for legislator and national assembly representative. That was his first access to political events. “I didn’t really participate much, just helped with putting up posters and handing out flyers.” He recalled his impression then, “one night I went to the plaza outside NTU front gate for their speech, and I was stunned! They were all criticizing the government, I thought I had stumbled upon a communist gathering.”

But in the following year, Malieyafusi Monaneng went into a coma for two months in the hospital due to a car accident, and he woke up almost totally blind. Shortly after, he suffered from tuberculosis and coughed up wisps of blood. Chen Gu-Ying invited him back to the house to rest for few months and looking at the many left-winged books in the room, he thought, since he had nothing better to do, might as well read while he still had a little eyesight in the left eye. This opened a new door for him.

Malieyafusi Monaneng turned totally blind at the age of 27, after which, he began learning the skill of massage and writing with braille at the Institute for the Blind of Taiwan. Less than a year after leaving the institute, he discovered that he had thyroid cancer and underwent surgery and treatment. Despite the endless suffering, he maintains optimistic, and often introduces himself as, “herded laboring animals at home before 16, and became a laboring animal in the city after 16.” When people ask him how he became blind, he replies, “I was punished for being a peeping Tom.”

April 13, 1987, indigenous groups protested at the Executive Yuan against Tongpu grave-digging, Malieyafusi Monaneng carrying a crucifix.

Free Our People Ourselves!

Opposition movements began blooming in 1980s. Malieyafusi Monaneng made acquaintances with prominent indigenous movement activists including parangalan and Iycang.Parod, and formed a study group to discuss social issues. “When I understood that the oppression we suffered was not because we were stupid, but because of the entire social structure and national system, I knew that we must free our people ourselves!” He and parangalan drank alcohol with blood, took a scared oath and swore to fight for indigenous peoples. Ever since then, Malieyafusi Monaneng could be seen wearing tinted glasses and holding a walking stick in every event, including pulling down the Wu Feng statute, Give Back Our Lands Movement, and saving children from prostitution.

Having always had an interest in literature, with his experiences in study groups, Malieyafusi Monaneng began writing poetry after the Taiwan Indigenous Peoples’ Right Advocacy Association was established. He laughs and says that many of which were impromptus after he had been drinking, “when people asked me to repeat it the day after, I had already forgotten that I even sang them in the first place.”

Writing poetry as a blind person is not easy, when you haven’t seen words for a long time, you gradually forget them. But Malieyafusi Monaneng says, “writing poetry itself is not difficult, but very painful sometimes, when I write, I recall what it had been like then.” Despite saying so, Malieyafusi Monaneng found a way out in life during the process of writing poetry and taking part in social movements. He once wrote in The Barbarian Shot Down, “making acquaintance with undergraduate students delivering indigenous social service, and befriending many non-indigenous friends through them, helped me through the various sufferings in life in the latter half of 1970s. There were people who helped me ‘accept’ the problems, and that was how I came back repeatedly from the edge of breaking down and despair.”

Darkness is Not Scary;

You can See with Your Heart

After the September 21 earthquake, Malieyafusi Monaneng became the convenor for the 921 Indigenous Community Squad, and hiked for hours to reach the mountains. People asked him how he could provide disaster relief if he can’t even see? He replies, “If I can make it here blind, indigenous peoples who have endured hardship will definitely make it through.” He encourages the victims, “darkness is not scary, you can see with your heart.”

The indigenous community squad dissolved after immediate disaster relief was provided, but they also came to realize that many indigenous villages were in situations just as bad and required assistance. They then transformed the squad into a permanent organization, supervising government policies and pushing for amendments, thus facilitated the adoption of Indigenous Peoples Basic Law.

Malieyafusi Monaneng has endured great sufferings throughout his life, how has he persisted in the journey of social movements? He replies without hesitating, “I hope there will never be others like myself or my family again! I don’t mind more suffering, the difference between 99 and 100 is minimal!” Last year, Malieyafusi Monaneng assumed the position of board director at Taiwan Multi-Indigenous Cultural Exchange Association, helping long-term care organizations in indigenous communities in purchasing supplies. Despite totally blind in both eyes, he sees clearly in his heart and continues to sing for indigenous peoples.