As a non-indigenous photographer who has all the updates on various indigenous friends, his mobile phone is filled with messages of recent conversations. Huang Tzu-Ming has been photographing indigenous issues for over 30 years. He has thousands of pictures describing the development of indigenous peoples and how much he cares.

A photojournalist from Tainan, Huang Tzu-Ming originally worked as a product designer. Later on, to help out a friend, he briefly joined a magazine publisher to help out with photography. He never out down the camera since. After working in a financial magazine publisher for a while, he grew increasingly tired of commercial photography and instead became attracted to what was happening to this land. He learned of the on-going protest against the Tongpu grave-digging incident then and visited the site with his camera, an event that forever changed his impression of indigenous peoples.

Before his photographing of indigenous movements, Huang Tzu-Ming knew nothing about indigenous peoples. It was when he gained firsthand knowledge of their demands did he really understand the oppression and discrimination indigenous peoples face. “Taiwan society used extremely chauvinistic, the older generation used to tell us that indigenous peoples are ‘barbaric’ and we didn't know any better. After I started working, and later on learning of their demands, I can't help but wonder ‘how could the government treat them so brutally?’” Huang Tzu-Ming recalls his disbelief.

Seeing is Believing,

Feeling that Strong Psychological impact

“April 3, 1987, indigenous peoples from Tongpu traveled north to Bo’ai Special Zone to march in protest, I marched with them carrying my camera, it was something we wouldn’t have imagined doing during the martial law period.” Even after 30 years, Huang Tzu-Ming still recalls vividly what happened that day. January the following year, the newspaper ban was lifted, Huang Tzu-Ming left the magazine publisher and joined the Independence Morning and Evening News, mainly interviewing political and social movement events, which engaged him in a series of indigenous peoples’ protests from 1980s to 1990s.

Huaxi Street March against Child Prostitution, Give Back Our Lands Movement, Nuclear Waste on Orchid Island..., turning on the computer, images from these indigenous movements are all organized with individual files, properly stored in his laptop. “I don't see myself on some mission of justice, work just so happens allows me to get up and close to these issues and record images on site, if they can be seen by others or create some kind of influence, that gives this news report its value,” says Huang Tzu-Ming.

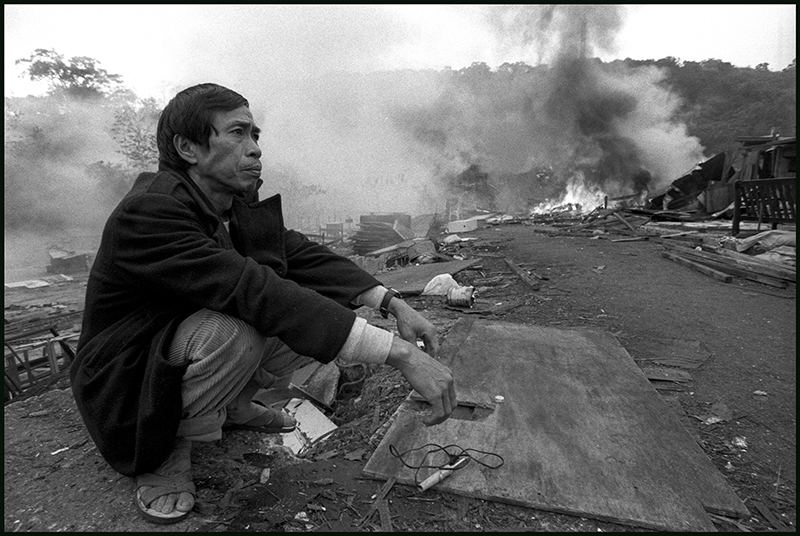

Huang Tzu-Ming has taken part in countless events and taken more photographs than he could count, what left him with the biggest impression was the relocation of Huatung Community in Xizhi at the end of 1990s. Huatung Community was the largest urban indigenous community in north Taiwan. The government expropriated the land to build a switching yard for Taiwan High Speed Rail, while over 200 households faced forced demolition of houses and relocation. January 4, 2000, was the deadline for house demolition, Huang Tzu-Ming arrived early at the scene to take photographs. The remaining residents invited him to join them for breakfast, and drink rice wine and chat. After breakfast, Hai-Lun, one of the residents, personally set fire to his own house.

The houses in Huatung Community were built by these people single-handedly, they would rather destroy the houses themselves than have the government demolish them. “I stood there watching them burn their house down, smelt the thick smoke. Can you imagine that kind of psychological impact?” recalling the ending of this forced relocation movement, Huang Tzu-Ming’s eyes darkened.

Huang Tzu-Ming documents the process of Pangcah youth troupe learning traditional crafts at Ziqiang Community in Taichung and photographs the tattoos of their indigenous names on their arms.

Are We Passers-By,

Or can We Become Friends?

At every indigenous movement, Huang Tzu-Ming can be seen capturing the scene with his camera. After a while, he became friends with participants who took part in the movement. Sadly, as the protests ended, achieving the interim goals of the movements, some people returned home while some moved away, he lost contact with these indigenous people. In 2017, Huang Tzu-Ming was invited by Nylon Cheng Liberty Foundation to create a photography exhibition on human rights issues. Recalling that it has been 30 years since the first indigenous movement, he decided to title his exhibition “the Journey of Indigenous Movements”.

After sorting through the photographs he had, Huang Tzu-Ming thought to himself, “it would be boring to just show photographs about what once happened.” He came up with the idea to photograph the people who once participated in indigenous movements, see how they are doing now, and highlight the development and changes of indigenous issues. But without Facebook or LINE in the old days, no contact information remained, how could he find those people again? In addition to using the connections he made over the decades of working in the media, he also traveled between indigenous villages with his laptop, going old school by showing people photographs for identification.

“That owner has been around for a long time!” “That's XXX's mother!” Huang Tzu-Ming held many “tell me who you recognize” gatherings in many indigenous communities, one after another, the people pointed at photographs on the screen and recognizing friends and family in delight. This searching process was also documented by Huang Tzu-Ming on his mobile phone and exhibited accordingly, showing the audience how this exhibition came about, and the lives of these people nowadays.

“I gave it a lot of thought while curating this exhibition, I’m a photojournalist, and my relationship with the interviewee ends the moment I leave the scene. But during the process of searching for these people, I kept asking myself, ‘what role am I playing?’ are we passers-by or can we become friends?” Huang Tzu-Ming felt that he has become bored of journalism, “so I shot documentary instead, and think about whether there is more I can do as a media person?”

From the results, it seems that Huang Tzu-Ming found his answer. Now, his mobile phone is filled with contact information of indigenous friends, he is constantly up to date with the fairings of most, and if anyone travels north, they look him up for tea and chat. With convenient internet communication applications, they often drop one another messages just like long lost friends, and cherish their friendships even more.

The Kavalan people is the only one using banana fiber to weave fabric, Huang visits the PatoRogan Community in Hualien to photograph children chopping down banana trees.

Photography

is Also a Form of Social Movement

Over the past three decades, awareness of indigenous rights is picking up, even though the activists rocking indigenous movements have retired, Huang Tzu-Ming has never left. He turned to documenting indigenous cultural affairs. “Just like indigenous movements in recent years, they have not disappeared but changed their focus, I am now more concerned about how youth in indigenous communities promote cultural,” shares Huang Tzu-Ming.

Still working as a photojournalist at a news agency, he uses his time off work to travel the various indigenous villages for photography and interviews. He recently went to Ziqiang Community in Taiping, Taichung, and documented the return of youth to the indigenous community to learn from elders the traditional culture, and their tattooing of their indigenous names on the arms. Under the influence of these older youth, children in the community are naturally drawn to their indigenous culture, and dance and play to indigenous songs after school.

His photography of indigenous movement issues is work, and personally isn’t an indigenous person, why has he persisted on this journey for so long? Huang Tzu-Ming believes that there are human right issues in any country around the world at any time, if you don't defend it, the rights regress, “photography is also a form of social movement, you need to invest over a long term and although it may not necessarily change the society, I preserve these images, and perhaps one day, it will become a window for the world to get to know the society.”

Hai-Lun, Huatong Community resident at Xizhi, sets fire to his own house, then squats and stars into the distance.

The Journey of Indigenous Movements by Huang Tzu-Ming