The “Three Generations Theory of Human Rights” proposed by the French scholar Karel Vasak is known for dividing human rights into three separate generations based on the development of human rights: 1. civil and political rights; 2. economic, social and cultural rights; and 3. developmental and environmental rights, rights of solidarity, and the right to peace. Here the rights of solidarity, also known as collective rights or group rights, refer to those rights that are enjoyed by virtue of sharing a collective identity, such as women’s rights, children’s rights, and minority rights.

The obligation of a state to protect the rights of ethnic minorities arises from the duty to ensure their equal status in society. The government, on the one hand, should work to prevent ethnic minorities from continued stigmatization, while on the other hand, seeking to compensate for the injustice they have suffered. Traditional liberalism holds that collective rights are incompatible with individual rights, arguing that the former could be a potential threat to individual liberty. From a communitarian perspective, however, the individual is inseparable from the community and society as a whole. The rights of individuals are based on the premise that the rights to survival and identity of ethnic minorities are guaranteed. Given this, the current international trends suggest that simply guaranteeing the individual-centered right to survival and anti-discrimination principles is hardly enough. Further actions should be taken to protect collective rights.

According to the Canadian scholar Will Kymlicka, the rights of ethnic minorities comprise those to culture, autonomy, and political participation. Indigenous rights can be viewed either as one of this kind in a broad sense or as a unique type of collective rights. They are most distinct from other ethnic minorities’ rights in that they are pre-existing and inherent to indigenous peoples, rather than delegated by the states or others.

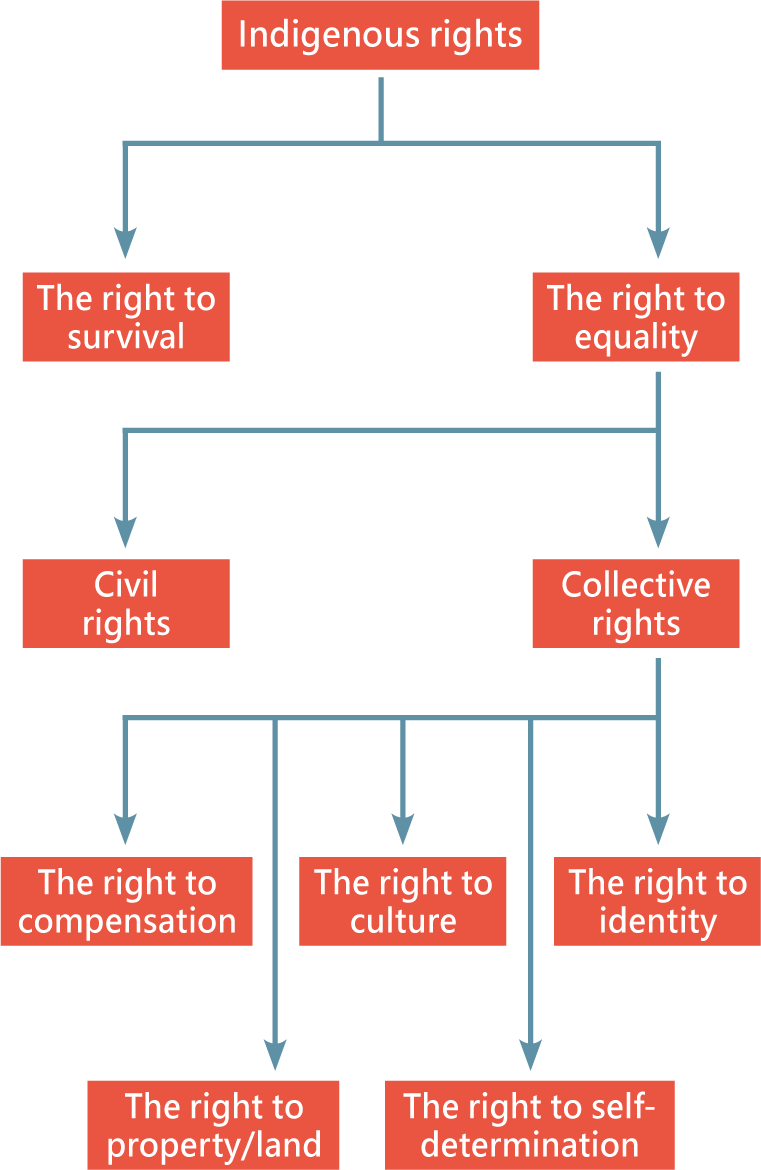

Following the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), here we divide indigenous rights into two major categories: the right to survival and the right to equality. The right to survival, or the right to life, concerns the guarantee of basic survival of indigenous peoples, while the right to equality deals with the active promotion of their basic rights, which can be further classified into civil rights and collective rights. The former is concerned with protecting individuals from discrimination, while the latter takes care of various rights that concern indigenous people as a whole, including their rights to identity, self-determination, culture, property/land, and compensation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Classification of Indigenous Rights

The Right to Identity

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and develop their unique collective identity and define themselves as indigenous. This means their identities and identification should not be imposed by the state or others but rather defined by themselves. Note that the so-called self-identification here does not apply to those who claim to be indigenous in their own right. The consensus of the community must be achieved to serve as the criterion, otherwise, the unique indigenous identity can become an easy target of exploitation.

The Right to Self-Determination

This refers to the right for indigenous people to determine their political status and to pursue their economic, social and cultural development. Simply put, the right to self-determination is a collective right that empowers indigenous peoples to handle their future and destiny, which can be said to be “the mother of human rights.” This has been clearly defined by the United Nations in the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Right (ICCPR) and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). And there are no other international laws or codes that prohibit indigenous peoples from exercising their right to self-determination. Hence the indigenous right to self-determination is equally effective as any of its counterparts in the world.

While exercising their self-determination right, indigenous peoples may also demand political separatism, or instead embrace cultural integration and assimilation. There is considerable room for imagination between the two extremes of the spectrum. Indigenous communities may be willing to accept various forms of autonomy or self-government offered by the state. But this doesn’t mean that they abandon their right to self-determination. Rather, they accept the arrangement temporarily, depending on to what extent the state protects or makes concessions to guarantee their other rights.

Opinions differ on what makes appropriate units for defining the scope of indigenous autonomous regions (see Figure 2). Up to now, it has been generally held that peoples or ethnic groups be used as the major criterion. The various autonomous regions thus defined can be further integrated into a pan-indigenous confederation. For those ethnic groups who claim larger traditional territories, they may adopt a compound model of autonomy featuring multiple “sub-nations,” namely, “a single indigenous people with multiple autonomous regions.” On the contrary, when an area is inhabited by mixed ethnic groups, residents can carry out an inter-ethnic/cross-national autonomy, characterized by the joint government of different peoples. That is, a “single autonomous region with multiple indigenous peoples.” In the case of tribal autonomy, the major concern is how to enforce community integration to prevent buying off and internal division.

Figure 2: Units for Indigenous Autonomy

The Right to Culture

The characteristics of a culture are truly reflected in the way people think, speak, act or interact with others. However, the systematic destruction of a culture, or cultural genocide, can lead to the extermination of a people without shedding a drop of blood. Hence, for indigenous peoples to sustain their cultural lifeblood, they should have the right to retain their languages, religions, traditions, customs, and ways of life. Particularly at the language level, in addition to the right to learn their mother tongues, they should have the right to receive education in their native languages. Meanwhile, the government should not implement any laws and policies that are assimilative or integrative. In recent years, the right to culture has been expanded to include the protection of and appropriate compensation for indigenous cultural and intellectual properties, including access to traditional secret remedies.

The Right to Property

Aside from the cultural and intellectual properties mentioned above, the indigenous peoples’ right to property generally implies their rights to land and natural resources. For indigenous peoples, the spiritual and material basis of their cultural identity can only be maintained through their link to the land, or a sense of belonging. The deprivation of their connections to the land implies the decline of culture and loss of identity, which could render their existence meaningless. In other words, as far indigenous people are concerned, the lack of land rights is tantamount to the infringement of their right to cultural identity, in turn making the pursuit of the right to survival a pointless endeavor.

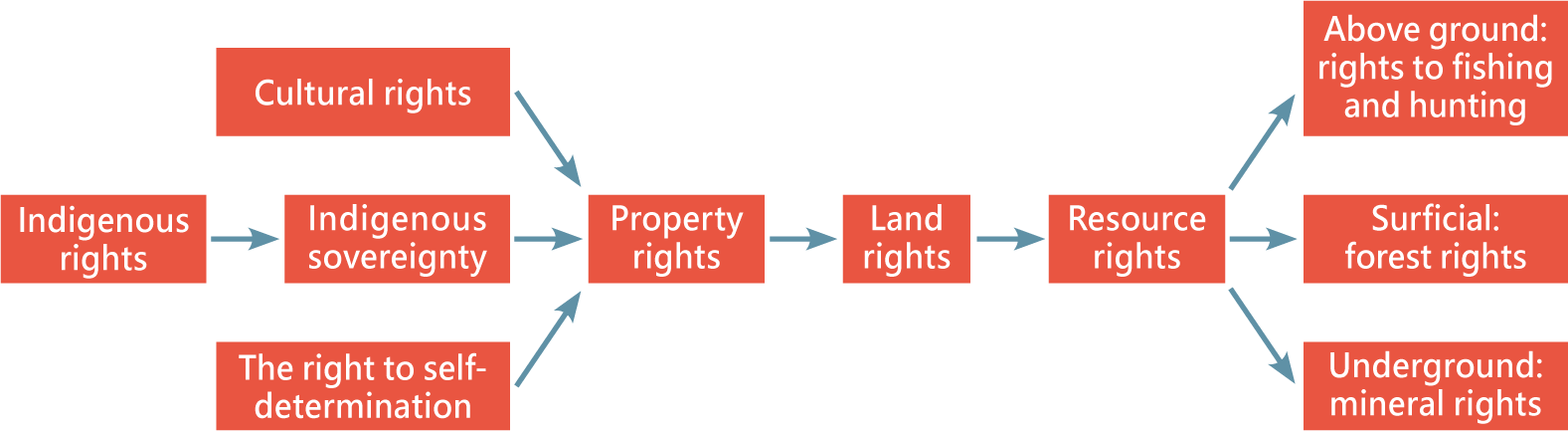

Land, in a broader sense, can refer both to land and sea area, which highlights the necessity to distinguish between “land country” and “sea country.” In this regard, the indigenous land rights also concern sea domains, namely, sea rights. Besides, the right to natural resources should also be counted as part of the land rights, but the two are generally referred to together as the rights to land and resources. As Figure 3 shows, it can be further classified into several categories, including the rights to fishing and hunting, forests, and minerals.

Figure 3: The Indigenous Land Rights

The source of indigenous property rights comes in two types: substantive rights and procedural rights. The former includes indigenous sovereignty and cultural rights, while the latter is a derivative of the right to self-determination. Indigenous sovereignty refers to those rights acquired through prior occupation or utilization and thus overrides all the other indigenous rights. Its derivatives include the rights to land and various resources.

For indigenous peoples, culture can be expressed in various forms, such as a unique way of life associated with the use of land resources. Due to the fact that they have the right to retain their cultural characteristics, and that natural environment and land resources serve as the fundamental basis for the sustainability of indigenous culture, the protection of the environment, particularly land, becomes a prerequisite to the guarantee of indigenous cultural rights.

The right to self-determination is a kind of procedural right. This means that indigenous peoples are entitled to determine the arrangements of political, economic, social, and cultural affairs related to their properties, land, resources, and forests. In other words, when the government intends to exploit natural resources that concern related indigenous rights, it must solicit the opinions of local people in advance and allow them to participate in the decision-making process. To put it concretely, when applied to the exercising of resource rights, the right to self-determination can be realized in the forms of public participation and access to information. The former denotes the situation where those who are likely to be affected by policies have the right to participate in the decision-making concerning the utilization of resources. This entails that these participants have the right to voice their opinions to be heard and to influence the decision-making process. The latter suggests that people have the right to gain access to information about potential environmental risks to ensure their quality of life, especially when the government’s actions may cause damage to the environment.

In short, the state must recognize and guarantee indigenous peoples’ rights to possess, develop, control, and utilize their shared land, territories, and recourses. If these rights are denied without free and informed consent, an attempt must be made to return them. If it’s practically difficult to do so, just, fair and prompt compensations must be provided.

The Right to Compensation

It’s often the case that foreign settlers seize the land of indigenous peoples without their consent, showing no respect for their unique ways of life and needs when exploiting natural resources. This contributes to the inherent guilt on the part of colonizing settlers. Hence the authorities must take active compensatory measures to repair the damage caused by the past social discrimination and political oppression against them, as well as the plunder of their native land. The least that can be done is to provide guaranteed opportunities in education or employment. A more positive approach, on the other hand, is for the colonizing country to make compensation for indigenous communities.

Shih Cheng-Feng

Shih Cheng-Feng

Professor at the Department of Indigenous Affairs, National Dong Hwa University. His specialties include ethnic politics, international political economy, and comparative foreign policy. He is also the author of “原住民族的權利與轉型正義” and “原住民族的主權、自治權與漁獲權”.