Lost and confused about their plains indigenous peoples’ identity, a group of “no-names” decided to find the answers in writing. This is Taiwan’s first cross-peoples writing project and the first piece of popular literature about the Taiwan plains indigenous peoples. Through the words, the authors soothed themselves and healed others.

In 2013, indigenous students from universities all over Taiwan took part in Taiwan’s largest anti-nuclear march. This is also where a group of young people from different peoples who felt confused about their identities met each other.

Society usually slaps a “plains indigenous peoples” label on this group of people and flippantly says that they have “assimilated into Non-indigenous culture”, erasing the history, culture, and even identity of these peoples. “Back then we were severely anxious about our identity. It got so bad that every time I met new people and they would ask which peoples did I belong to? I would feel very stressed and confused.” Chen Yi-Zhen of the Makatao people recalled.

In 2014, five youths came together and began a five-year-long writing project on Facebook. This group, which called themselves “The No-names”, traveled around Taiwan to interview and document the stories of twenty indigenous youths who were also confused about their indigenous identity. The life stories were eventually compiled into a book that was published in 2019. Yu Yi-Te of the Makatao people explained that “in addition to identity, we were also interested in the lives of each person. We wanted to see the differences between our experiences and theirs.”

Braving Through Chaos and Uncertainty,

Using Actions to Make Changes

“Writing was like a self-healing process.” Chen Yi-Zhen recalled. Every long holiday, they would gather at Yu Yi-Te’s home in Pingtung to write and discuss the content. During the discussions they realized, “It is what it is! Why can’t we just let it go?”

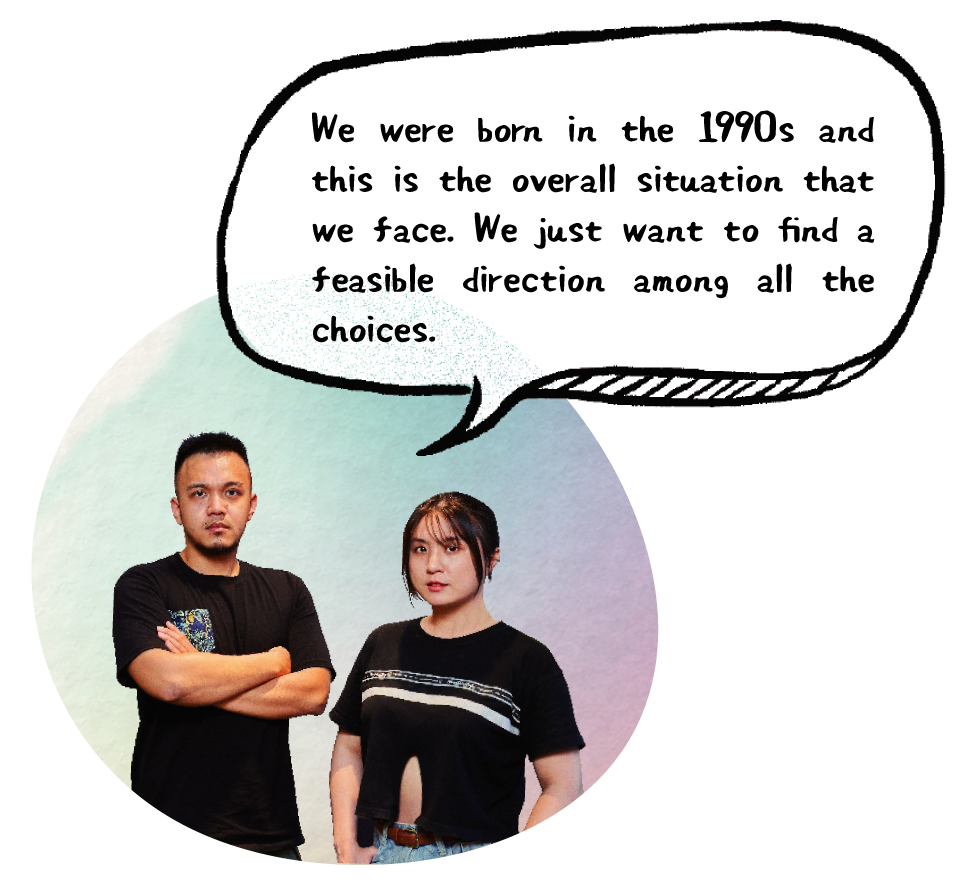

“It’s not our fault our peoples intermarry or the indigenous peoples are becoming more urbanized. It’s not up to us that we have a “messy lineage”*, can’t get an indigenous ID, or do not have an authentic community experience. We were born and raised in this generation and this is the overall situation we grew up in. We’re just trying to figure out a feasible direction among all the choices.” Chen-Yi-Zhen said frankly.

* People who are “not like an indigenous person” due to intermarrying or certain traits would joke that they have a “messy lineage”.

After completing and publishing the book The No-Names (沒有名字的人), the five authors do not have any further writing plans at the moment. Yu Yi-Te shared that “writing helped us get through that chaotic and uncertain period. Back then we had the anxiety of ‘are we were indigenous or not’, but now we are more resilient. We do these things because we want to, not because of our lineage.” There are four members currently working on research related to indigenous peoples’ cultures. They firmly believe that writing is not the only way to make changes.

Now, they do not feel that their identity is a burden anymore. “People don’t know you, they don’t know your people, either. It’s not something you can change with a few words. Later I realized that ‘actual action’ is key.” Chen-Yi-Zhen said. “Regardless of which peoples the person belongs to, the way they use their bodies and actions to carry out their own thoughts and beliefs is more important than a lineage certification or household registry.”

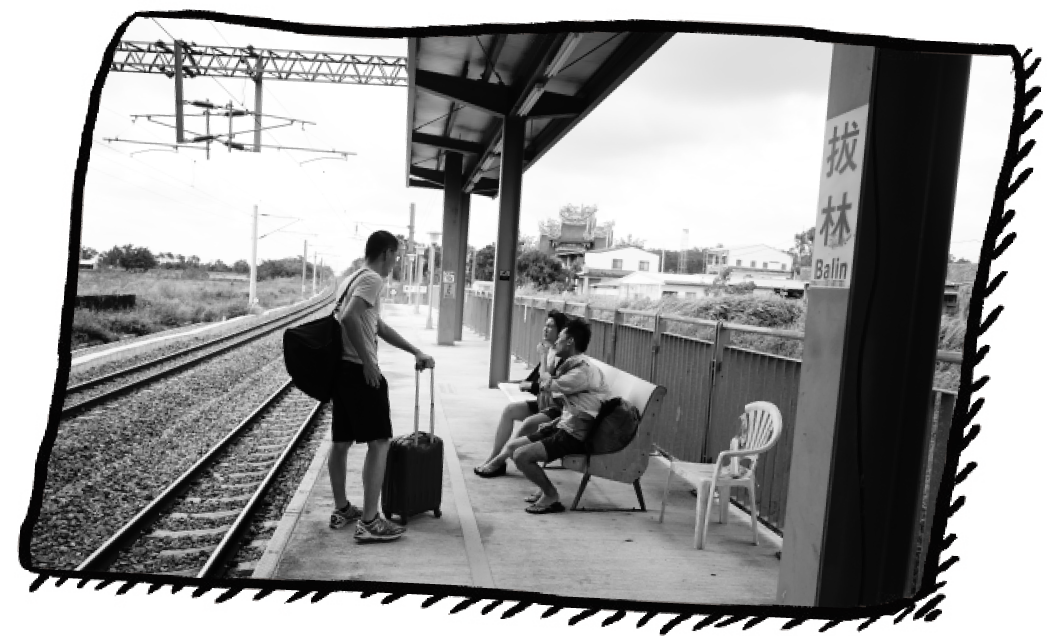

The five-people team visited many Taiwan plains indigenous peoples’ villages to collect stories.

With Facebook,

the Group can Act Faster

Although The No-names is not an activist group, they are still very active in indigenous communities and are all members of the Indigenous Youth Front. They often show their support of indigenous issues under the name “The No-names” to express the opinions of plains indigenous youths.

Facebook was on the rise when this group of young people, which were born in the 1990s, formed The No-names. “The new tool gave us a platform to swiftly react, disperse information and publish articles.” Yu Yi-Te commented. Chen Yi-Zhen explained that in the past, social movements relied heavily on interpersonal relationships - people had to actually meet and know each other. “But with Facebook, we can spread the word out faster. Every community or club has a leader, if we can reach out to the leader, it would be the same as contacting all the university students in that community or club.”

With the internet readily at hand, strategies for disseminating information have become more flexible. On Facebook, The No-names tells long stories about the lives of each member. Compared with serious and rigid statements, the captivating narrative is more accessible and easily accepted. The No-name accumulated a lot of fans within a short time and successfully raised awareness on indigenous issues. Chen Yi-Zhen pointed out that “a lot of readers commented that they felt something after reading our stories and began to seek out their roots, too.” This also affected other indigenous communities and they started to use more approachable ways to share their life stories on Facebook.

The five-people team visited many Taiwan plains indigenous peoples’ villages to collect stories.

Reaching Out to More People

The indigenous movements in the 1980s talked about land ownership, name rectification, saving underage prostitutes, and labor rights. “Now we are still talking about land ownership, but in more detail. And thanks to the internet, these ‘case study’ type issues can reach more people faster.” Yu Yi-Te explained. For example, the Jhihben optoelectronic development project, Oppose Meiliwan movement, nuclear waste on Orchid Island case, and the forced relocation of Ljavek Community in Kaohsiung are all regional issues and involve different policies and regulations.

“We realized that a lot of issues are not just the problem of one certain group or community, but exist on a regional, social class, or gender level.” Chen Yi-Zhen pointed out. For example, in the Ljavek Community forced relocation case, the two opposing parties are the government and the residents who are fighting for justice of the right to adequate housing and land ownership rights. For gender issues, they are fighting against the patriarchy.

This new generation is extending their scope from the petitions of past indigenous movements and gaining experience from different issues. When Chen Yi-Zhen was in university, he was exposed to the issue of “anti-commoditization of education”. He learned how to study related provisions, how to form his discourse, and use this as a foundation to write speaking notes. He even learned to make tree diagrams to show all different aspects of the issue, their relations, and how to respond to the challenges. “Later this became a habit. If I encounter an issue, I’d go look up the related provisions and try to form my own or the group’s discourse.”

When they began, they were trying to figure out their names while actively being involved in indigenous peoples’ issues. Now they have found a feasible direction and are marching onward to find the answers.