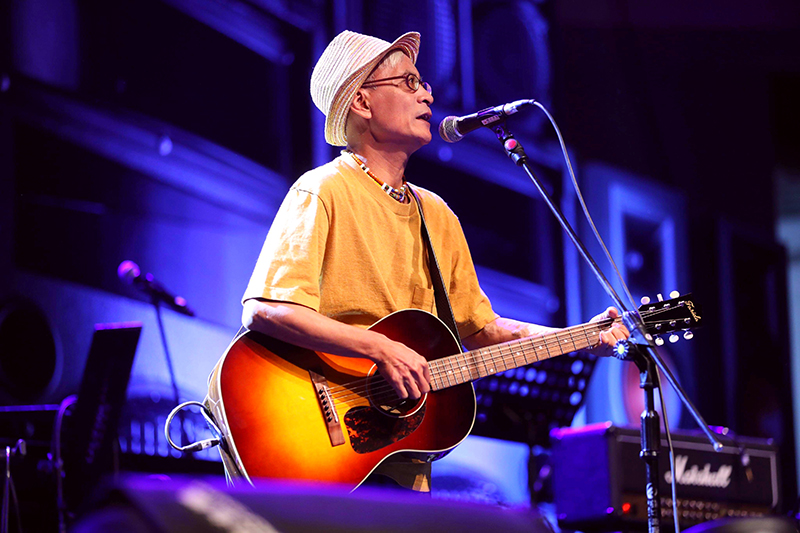

Turning from fighting for indigenous rights in the streets to questioning of self as “man”, Dakanow’s music journey is both radical and unrestrained. He says with unruliness, “I write and sing songs not for commercial profit or audience support, for me, music is life.”

Dakanow is a singer with social movement background, traveling between different indigenous movement scenes carrying a guitar on his back, vocalizing the disadvantaged situation of indigenous peoples with songs. He cares about land and culture. Like a well-traveled bard, with poetic lyrics, he sings about the life journey of driftwood, the harm caused by Typhoon Morakot to the land.

Born in Majia Community in Pingtung, Dakanow grew up listening to the singing of elders in his indigenous community, especially his grandmother who raised him. She used to sing traditional songs while working, and taught Dakanow the norms, knowledge, the spirit, and value of their indigenous group, inspiring his imagination in music. “Other than language, man pass on their culture with a different sound, so we can understand the problems we are facing now and know where to go in the future,” so says Dakanow.

Sing Our Own Songs,

Indigenous Peoples Be Our Own Masters

Campus folk song was popular all over Taiwan in 1970s, Li Shuang-Tze, Yang Hsien, and parangalan initiated the folk song movement, encouraging students to pick up guitars and sing their own songs. Still a high school student then, Dakanow began learning to play the guitar, “guitars are affordable and easy to carry, it was a convenient musical instruments for the economically-challenged indigenous peoples back then, and therefore became a rather important influence to contemporary indigenous music,” shares Dakanow.

The folk song movement was prevalent in the urban area, but its influence was rather limited in indigenous villages. For indigenous peoples, guitar was merely an instrument that can play music, the real spirit of the folk song movement, namely the concept of demonstrating individual subjectivity, freedom, and human rights with song-writing and singing, had yet to really be universal in indigenous communities. Even Dakanow didn’t grasp the real spirit of the folk song movement until he began university in Taipei, he heaved a great sigh, “I realized then that singing itself comes with such powerful social meaning.”

During his university years, Dakanow witnessed the rise of indigenous movement, with influence from his indigenous peers and predecessors, he began contemplating his own identity. “The nation calls us ‘aboriginals’, it is insulting and not the name we want, we should have the right to decide our own name and be our own master.”

The spirit of freedom and subjectivity advocated by folk songs matched perfectly with the ideals proposed by indigenous movements, and Dakanow took to the streets with his friends and demanded name rectification. In 1986, he wrote his first song Really Home Sick, singing the torment and helplessness suffered by indigenous peoples in the mainstream society. Since then, music became his weapon towards the system and his voice to the society.

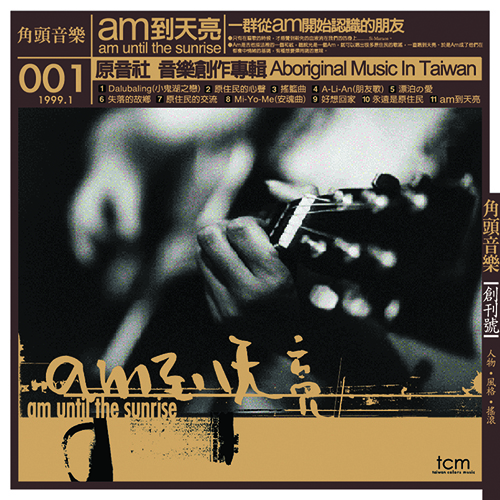

Am Until Sunrise is an album with extremely strong indigenous identity.

Indigenous Music Society is Not a Musical Group

but a Social Movement Group

Indigenous movements ceased and activists moved into two directions in 1990s: return home to develop their indigenous communities, or move into politics. Dakanow resigned from his teaching position and began studying at Yu-shan Theological College & Seminary, where he formed the Indigenous Music Society with Kinepele and Ibun who were also students at the seminary. Dakanow says, “the Indigenous Music Society is not a musical group, but a social movement group in fact.”

The Indigenous Music Society believed that after the fruits of indigenous movements have wholly been absorbed by the political system, the society still requires a protesting force outside the system to counteract the influence. Sticking to the streets following the spirit of indigenous movements, the Indigenous Music Society used music as medium to continue discussing issues regarding indigenous rights, “we record our journey with music, for example, Always Indigenous and Hometown Changed are songs we wrote with our people,” says Dakanow.

During this period, underground music bloomed in Taiwan, many non-mainstream and niche independent bands gained popularity in the market. In 1998, Taiwan Colors Music produced and released the album Taiwan Independent Compilation, which included music by bands focusing on different social issues such as Mayday, Quarterback, the Chairman, and Indigenous Music Society. “This album was monumental, representing the energy accumulated by underground music in Taiwan as well as how music provoke the social system,” says Dakanow.

Afterwards, Taiwan Colors Music continues to work with the Indigenous Music Society, and invited them to release their own album. To add more flavor to the album, the Indigenous Music Society invited other friends to the production team, including Cheng Chieh-Jen, Samingad, Maraos, and Hao-En. This album is a collection of various languages including indigenous languages, Mandarin, and Taiwanese, a fusion of traditional and contemporary indigenous music, and the title Am Until Sunrise was the namesake of the A minor chord, the favorite chord used in indigenous communities when they sing.

Am Until Sunrise is an album with extremely strong indigenous identity, though ladened with accusations, it is also humorous and optimistic. A refreshing musical momentum, the first album in Taiwan with indigenous issues as subject inspired the imaginations of later indigenous musicians in creating indigenous music.

Past performance of the Indigenous Music Society.

Culture is Not Gone,

Just Temporarily Forgotten

Since indigenous movements, the term “indigenous” seems to advertise a certain identity and value, yet having experienced first-hand the entire process, Dakanow have gradually developed different ideas, “we can embrace traditions more, but not rely too much on the term ‘indigenous’.” He believes that “indigenous” has become a framework, “the culture and knowledge passed on by our ancestors teach us to become a member of the social group, namely the existence of ‘man’. We must break away from the melodramatic accusations, let go of the special identity that is ‘indigenous’, before we can understand the value of ‘man’ in our traditional culture.”

In 2020, Dakanow released his third album NaLuWan, with music genres including folk, blues, rock and roll, reggae, anthem, and rap, exploring the past, present, and future of the NaLuWan and Kacalisiyan (the “people who live on the slopes” of the Paiwan people) groups. Many claims that the traditional cultures of the indigenous peoples are dying, but Dakanow believes that just as NaLuWan has been commercialized as stereotype and narrowed down to a mere indigenous musical symbol, traces of NaLuWan can still be found amidst the legends, music, dance, and language of the Kacalisiyan. “Culture is not gone, it is just temporarily forgotten, or drifted into another space-time. Maybe we will hear the singing of NaLuWan when we reach the outer space,” he laughs.

The angry youth who once fought the mainstream system with music has become soft and romantic after 40 years. “Music reflects the voice of humanity, and in my journey of song-writing, I always think about how to make the society more harmonious through my music, and that is the most important lesson my cultural root has taught me,” says Dakanow slowly.

1988, youth groups from various indigenous groups pulled down the Wu Feng statue in front of the Chaiyi Station. Photo Credit: Tsai Ming-De