Professor Hsu Tsang-Houei passed away on January 1, 2001. This year marks the 20th anniversary of his passing.

When I left for University, I went from Hualien for Taipei alone. In an elite class at the Department of Music at National Normal University I felt ignorant and tried to stumble through. I made a quiet decision to return to Hualien and teach Music after graduating, not too sure what path to pursue. In my junior year, I took Professor Hsu’s course. He knew I was the only indigenous student in the class and was full of curiosity and expectations for me.

Professor Hsu spoke of a field project gathering folk music in Pingtung, Taiwan’s western and eastern coastal areas during the 1950s. He had teamed up with Professor Shih Wei-Liang for a large-scale collection of old Taiwanese ballads and indigenous songs. During the two-year project, they discovered many of Taiwan’s celebrated folk music scenes, collecting around 3,000 pieces in total, including some 200 Hengchun ballads and sad songs and 2,800 indigenous (then called “highland people”) folk songs. The content of the indigenous songs had a rich vitality in theme and singing style. The music and dance were full of with profound cultural significance.

I lowered my head, listening to the Professor at the podium talk about this with joy. I seemed to have grasped the power of life. Could indigenous music be so rich? I grew up educated in Western music, learning directly from master Kuo Tzu-Chiu in junior high, but I’d never come to see the richness and unique value of indigenous music.

I raised my head to look at the Professor, wondering why he saw indigenous music, the music I’d been least interested in, as a Taiwan treasure. I remembered dances and music performed at harvest rituals from my childhood, then I started to think: besides the dancing and noisy action, did I really know Pangcah music? At that moment, I seemed to find my future direction.

Encouragement to Bravely Step Out of My Comfort Zone

A friend suggested I visit the Shih Wei-Liang Music Library on Zhongshan Road, Taipei. The library’s collection was roughly sorted, but as I browsed through the collection and the distant, unadorned songs came from my headphones, I tried to take the first step over the boundaries I had set for myself.

I thought I’d be happy enough teaching piano in Hualien after graduation. I never considered pursuing a master’s degree. But after a few years back in Hualien, I summoned the courage to visit Professor Hsu and tell him my interest in the master’s program at NTNU. I started learning privately at Professor Hsu’s house and showed my interest in indigenous folk music. My teacher picked out three recordings of indigenous folk songs to transcribe. They were free-beat chants in my mother tongue - which I couldn’t understand. It was an overwhelming assignment for me, so far removed from community life. It was only three songs, but it took almost a week to finish. When I handed in the assignment, a look of surprise appeared on the Professor’s face. After that, I embarked on an unexpected journey with my professor’s encouragement.

I followed Professor Hsu into academia and began to turn vague childhood memories of the music and dance into concrete discourse. Day after day, I documented, sorted, and collected music scores. That was the start of 30 years of fieldwork.

A Buffalo from a Student

Lin Xin-Lai and Li Tai-Hsiang, were two of Professor Hsu’s students working on the folk music collection project. The Professor shared with Panay Mulu interesting stories about his other indigenous students. One happened when the Professor was teaching at the National Taiwan Academy of Arts (now National Taiwan University of Arts). He had noticed that Li Tai-Hsiang was looking frail and found out he had no money for food. He took Li to a nearby noodle shop and told the owner to charge Li’s meals to his account, and that he’d cover the bill at the end of the month. When Professor Hsu went to clear the tab, imagine his surprise to find the bill was between 2,000 and 3,000 NTD when a bowl of noodles only cost 3 NTD! “How did you spend so much on noodles?” the Professor asked. Li Tai-Hsiang said that when his family in Taipei had no money to eat, they’d also charge meals to Professor’s account. Professor Hsu had doubts about the family repaying the debt, but Li Tai-Hsiang said he’d come up with a solution. A few days later, a buffalo appeared on the campus grounds. “To pay off the debt”, Li told the Professor. Professor Hsu just about passed out from shock and amusement, but he was sincerely touched at the thought of Li’s family leading the buffalo all the way from Taitung to Taipei.

A Model Teacher

I later asked Professor Hsu why he was so devoted to supporting talented indigenous musicians. He said that when Japanese scholar Kurosawa Takatomo visited Taiwan to research Taiwan’s indigenous music, he told him that “research into Taiwan’s music should be performed by Taiwanese scholars”. This sentence inspired Professor Hsu’s folk music collection project in the 1960s. Thirty years later, Professor Hsu passed the words on to me with heartfelt sincerity—“It’s only right for Taiwanese indigenous music to be studied by Taiwanese Indigenous scholars.”

Soon after the lifting of cross-strait travel restrictions, Professor Hsu visited China to collect data and for academic exchanges. He constantly reminded me to pay attention about how traditional indigenous music and dance was being preserved in China. At that time, exchanges between scholars on both sides of the strait were frequent. In 1993, Professor Hsu even took me to a seminar on Chinese minority music and introduced the concept of “indigenous peoples” as a collective term for Taiwan’s nine ethnic groups, rather than referring to a single “highland people.” Professor’s trips across the strait led to a wave of interest in domestic ethnomusicology.

It’s been twenty years since Professor Hsu Tsang-Houei passed. Few people in Taiwan’s music circles now mention his name, but his encouragement, support, and instruction are like bells and clouds in the distance over the sea that still resonate and inspire me. Professor Hsu’s words carry weight in the field of ethnomusicology. He was a humble yet courteous gentleman, always elegantly dressed, and ready to raise a glass to everyone’s enjoyment. He was a worldly man who associated with people from all walks of life, across social classes. He was polite to students and caring towards students of few means. He’d treat them at his favorite restaurants, and in this we can see how down-to-earth he was.

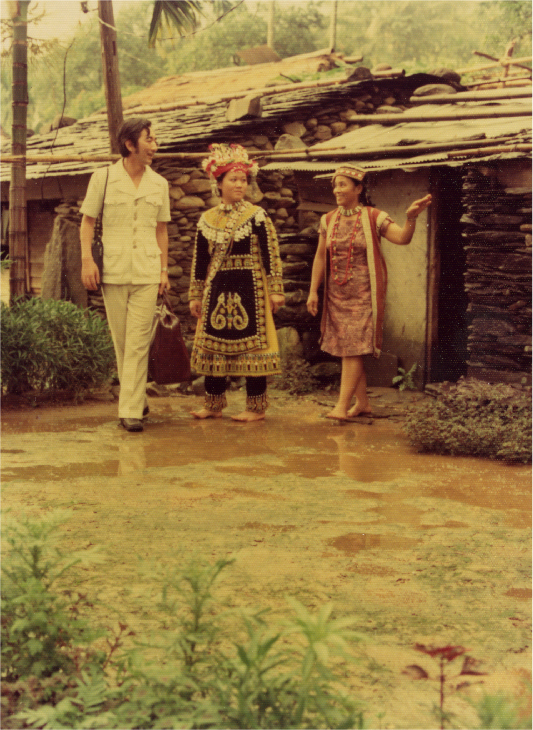

Professor Hsu visits Sandi Township, Pintung County in the summer of 1977.

Without Him, I wouldn’t Be Where I Am Now

I started my research on Pangcah ritual music and dance in 1984. After collecting and documenting materials in the field year after year, I had accumulated many questions. Ritual music and dance encompasses a body of rich and obscure knowledge, and Professor Hsu was always there, encouraging me to spend more time and effort compiling the audio-visual materials I gathered in the field, even if it was just a day’s worth of recordings of Mirecuk music and dance. In 1992, I was admitted to NTNU’s graduate program in musicology. In my thesis, I included a compilation of thirty-three Mirecuk songs, lyrics, and prayers, as well as a day’s worth of ritual recordings. The data and documentation may have been incomplete, but for me the experience was rewarding.

After graduating in 1995, I quit teaching to focus on researching indigenous music. With professor Hsu’s support and funding from my parents, I set up the Foundation?of Music of Taiwanese Indigenous Peoples, which opened up another lonely and unfamiliar journey.

Professor Hsu travelled frequently across the strait. He asked me if I’d go to China for a doctoral degree because there wasn’t a doctoral program in music in Taiwan. But I wasn’t good at foreign languages and never thought of going abroad to study, especially with the unclear cross-strait political situation. But with Professor’s great assistance I decided to go to China and broaden my horizons. Professor Hsu caringly referred me to my future doctoral advisor in China. After finishing my Ph.D., I did a research project “Music in the Spiritual World—Pangcah Ritual Music.” In it, I laid out the eight sets of three-note arrangement that shape musical properties and the supporting words (ha hai and ha he) used to highlight interactions between spirits. Without Professor Hsu Tsang-Houei, the room to structure the culture and knowledge systems of indigenous music would not have been possible, and it would not be possible for me to still be engaged in indigenous community research.

Professor Hsu Tsang-Houei meets Bunun people on August 6, 1978, during a visit to Zhuoxi Village, Zhuoxi Township, Hualien County.

Panay Mulu

Panay Mulu

Associate professor, Department of Ethnic Relations and Cultures, National Dong Hwa University. Panay Mulu specializes in ethnic music, indigenous culture exhibitions and performances, indigenous music and dance, Pangcah ritual culture, and music anthropology.

Publications:《繫靈:阿美族里漏社四種儀式之關係》,《靈語:阿美族里漏「Mirecuk」(巫師祭)的luku(說;唱) 》