In an interview in 2020, I inadvertently overheard that a local government/group had started to investigate the nomination of private antiquities as cultural heritage. That area has been equipped with relevant authorities and capabilities to engage in general surveys of cultural artifacts, and these experts have kept a good grip on the antiquities. In the hope of a higher and better level of preservation, they opted to nominate private antiquities in the town as cultural heritage. Once the antiquities are accredited as cultural heritage, the local government will apply to procure appropriate temperature and humidity control chambers, so that the local indigenous peoples in the area can store the cultural artefacts.

In an interview in 2020, I inadvertently overheard that a local government/group had started to investigate the nomination of private antiquities as cultural heritage. That area has been equipped with relevant authorities and capabilities to engage in general surveys of cultural artifacts, and these experts have kept a good grip on the antiquities. In the hope of a higher and better level of preservation, they opted to nominate private antiquities in the town as cultural heritage. Once the antiquities are accredited as cultural heritage, the local government will apply to procure appropriate temperature and humidity control chambers, so that the local indigenous peoples in the area can store the cultural artefacts.

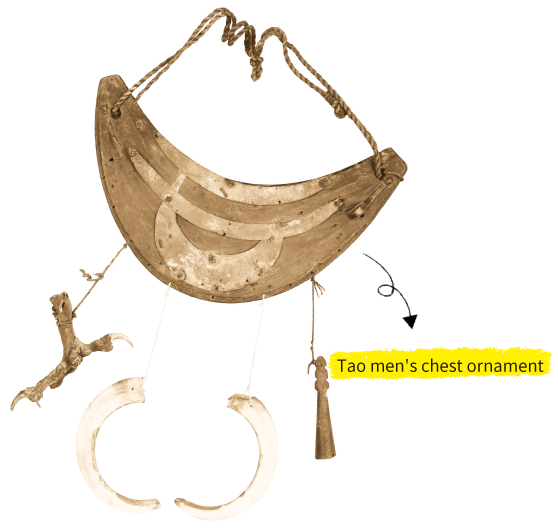

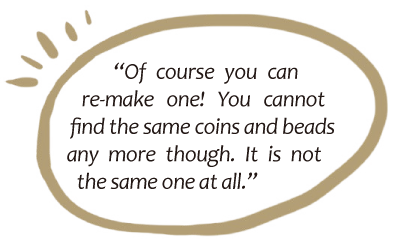

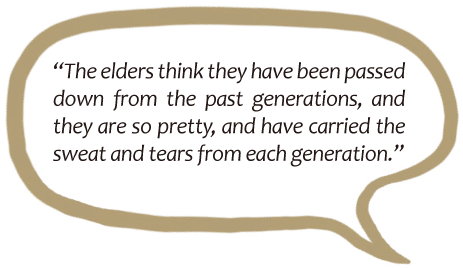

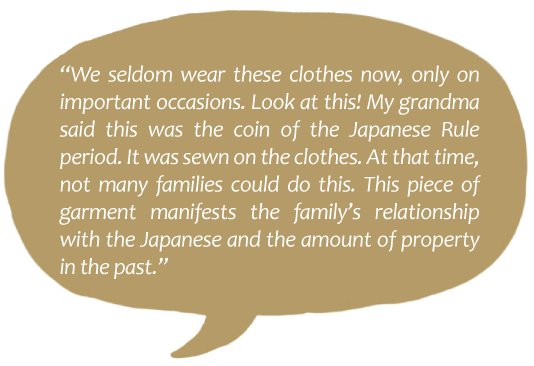

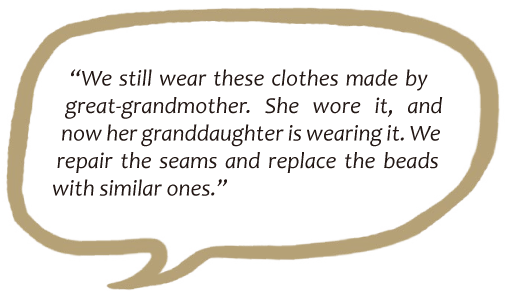

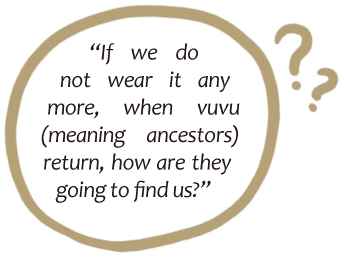

There are, however, some application details in the interview to be clarified. An example is a quandary in which the initiator (also a community member) and other community members would like the antiquities to be preserved in the best possible way, but they also long for the ownership of the objects. This could be vividly portrayed by the following conversations from the interview.

1. Uncertainties Surrounding Nomination/Designation Processes

Community member, “Today I heard that the nominated private artefacts could not be used any more.”

Administrator, “No, it could not. If you use it, it is not the original piece. It has been altered.”

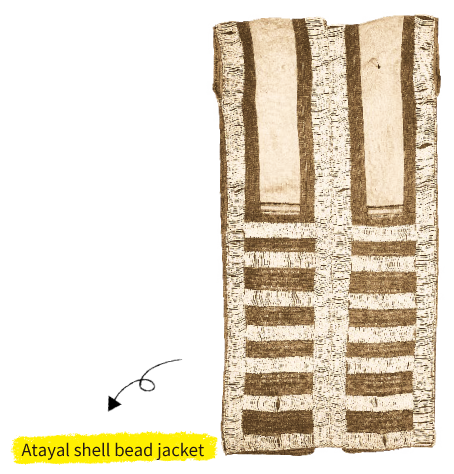

Community member, “What? Really? We still want to wear them though.”

Community member, “I have fixed here. Because I am still wearing it, of course I have to fix it, otherwise it falls apart! Will this affect its accreditation?”

Interview information 2020.07.10

It occurs to me that scenarios and concerns as such result from the uncertainties surrounding field surveys and subsequent reviews. In accordance with the National Cultural Heritage Database Management System of the Bureau of Cultural Heritage under Ministry of Culture, there are 110 indigenous peoples’ artefacts accredited as cultural heritage, and all of which are state-owned assets. This shows that the practice on nominating/designating indigenous peoples’ private antiquities requires more practical experiences. Particular emphasis should be placed on the composition of the relevant accrediting authorities, scholars, pertinent community participants. Also, the assessment “criteria/value” deserves more deliberate discussion. These are what make nomination/designation of indigenous peoples’ private artefacts uncertain.

As far as the classification of antiquities concerns, many scholars (Zhuang Yi-Hua, Zheng Lian-Yin, Liu Yiping, and Li Jian-Wei) have pinpointed that there is confusion regarding accreditation criteria, and have stressed that a more complete and clear definition and discussion on value is a prerequisite. Zheng Lian-Yin (2011) further pointed out the distinction between “artefacts” and “folklore” lies in whether one has been detached from its original locus, but when it comes to implementation, it is fairly difficult to draw a clear cut between both, and hence makes accreditation harder. In other words, more practice and discussion is needed in order to reach an appropriate classification approach and methods for the nomination and designation grading of Taiwan’s cultural heritage. The problem lies in the criteria/value. Another message that has derived from the interview is well worth considering.

2. An Object is Not Simply an Object.

Interview information 2020.07.10

In accordance with Article 68 in Chapter 5 of the “Cultural Heritage Preservation Act,” “In the event that a national treasure or significant antiquity as referred to in the preceding paragraph is lost or its value diminishes or increases, the central competent authority may revoke the original designation or reclassify the antiquity, and announce the revocation and reclassification.” The statements from the community members quoted earlier unravel the anxiety they have towards the artefacts. Anxiety rises from the preservation and use of the artefacts, which are still used within the original cultural domain, once they are designated as cultural heritage. We can also learn about their fear of the artefacts losing or increasing their value. By taking the cultural implications from the historical background and repairing skills into consideration, it is axiomatic that these artefacts are not purely objects to the owners, but carry cultural messages, memory, and even the memory of interaction with ancestors.

General Surveys of Antiquities are Not Equal to Nomination/Designation.

General Surveys of Antiquities are Not Equal to Nomination/Designation.

The Article 65 of Chapter 5 of the updated “Cultural Heritage Act” in 2016, stipulated that the competent authorities shall periodically conduct general surveys of antiquities, and hence, the Bureau of Cultural Heritage proceeded to conduct nationwide general surveys. As the Bureau of Cultural Heritage points out, the success of the general surveys lies in the survey method appropriate for Taiwan’s condition and the quality of personnel conducting surveys. As a result, developing such human resources is the priority, and the aim should be placed on equipping them with the ability to build archives, and conduct in-depth research.

To put it in other words, the objective of general surveys should not centre around the antiquities, but the process. Through compiling an inventory of antiquities and resources, we can learn about the strengths and weaknesses of the environment in which the cultural objects are, and the situation of current resources. Pertinent strategies can then be devised, so that a mentality of preservation can take root.

Consensus of Heterogeneous Practitioners

Consensus of Heterogeneous Practitioners

A further discussion about the first perspective on talent development and survey methods appropriate for Taiwan’s condition is that the talent development should not be limited to survey practitioners only. Instead, people working at all levels of general surveys or subsequent nomination/designation grading should all be included. Competent authorities, experts and scholars, and other personnel should all keep an open attitude when coming into contact with different knowledge systems, in order to identify approaches right for Taiwan’s situation or indigenous peoples.

Making Good Use of Regulations

Making Good Use of Regulations

“The regulation related to the following matters involving indigenous peoples’ cultural heritage shall be stipulated by the central competent authority and the central indigenous people authority jointly: 1. Investigation, research, designation, registration, revocation, alteration, management, conservation, restoration, reuse and other matters prescribed in this Act. 2. Cultural heritage that features ethno-cultural characteristics and cultural differences of indigenous peoples which cannot be classified under any category under Article 3.”

The aforementioned Article 13 in the first chapter of the “Cultural Heritage Preservation Act” indicated that the cultural heritage, which features ethno-cultural characteristics and cultural differences of indigenous peoples, and cannot be classified under any category under Article 3, shall be handled by competent authority. This Article has provided a breakthrough solution to the discussion about the preservation of indigenous peoples’ cultural heritage. The success to the practical operations and implementation of the resulted “Regulations Governing the Cultural Heritage of Indigenous Peoples” rely hugely on the local government, central competent authority, scholars and experts, and indigenous peoples, so as to construct a discourse that allows for different interpretation towards cultural heritage.

The aforementioned Article 13 in the first chapter of the “Cultural Heritage Preservation Act” indicated that the cultural heritage, which features ethno-cultural characteristics and cultural differences of indigenous peoples, and cannot be classified under any category under Article 3, shall be handled by competent authority. This Article has provided a breakthrough solution to the discussion about the preservation of indigenous peoples’ cultural heritage. The success to the practical operations and implementation of the resulted “Regulations Governing the Cultural Heritage of Indigenous Peoples” rely hugely on the local government, central competent authority, scholars and experts, and indigenous peoples, so as to construct a discourse that allows for different interpretation towards cultural heritage.

All in all, more room has been created for discussion and implementation of both the preservation of common cultural heritage and work related to indigenous peoples’ cultural heritage since the 2016 regulation amendment. What comes next is that we need to continuously practise and experiment with more flexible and variable methods instead of blindly sticking to particular criteria or narrative. This way, we will then be able to reach a consensus on how to preserve cultural heritage and new approaches that are right for our time.

全國文物普查及暫行分級資訊網

National Survey of Movable Heritage

—Refernces—

李建緯(2020)。〈臺灣古物分級制度發展之反思-從《文化資產保護法》談古物分級的進展〉。《文化資產保存學刊》54:97-115。臺中市:文化部文化資產局。

李建緯(2021)。〈臺灣古物分級制度之反思(下)-國有文物暫行分級現況分析〉。《文化資產保護學刊》55:7-27。臺中市:文化部文化資產局。

莊薏華(2009)。〈有多珍貴?古物類文化資產分級指定淺析〉。《檔案季刊》8(1):56-69。新北市:國家發展委員會檔案管理局。

劉怡蘋(2014)。〈價值、時間、抉擇、理論:布朗帝的修物哲學與我國《文資法》中「古物」的分類問題〉。《南藝學報》8:127-156。臺南市:國立臺南藝術大學。

鄭蓮音(2011)。〈解與結-博物館藏品古物分級與財產登錄〉。《博物館學季刊》25(4):17-27。臺中市:國立自然科學博物館。