Over the past 20-some years, Taiwan has seen two high-profile planned waves of indigenous participation in museums. The first wave began in 1995 with the Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines “Indigenous Village Special Exhibition” series, followed by the “Voice from The Tribes exhibition” shown at the National Museum of Prehistory in early 2000. Both exhibitions focused on the right to interpretation.

The second wave occurred in 2007 when Council of Indigenous Peoples proposed the “Large Museums Lead Small Museums” subproject under the umbrella of a revitalization project for local indigenous culture museums. Two prominent exhibition types were emphasized by the National Museum of Prehistory: “Collaborative Curation” and the National Taiwan Museum’s “Homecoming Exhibitions”. Both emphasize community empowerment, collaboration, and dialogue.

This second wave also involved the return of cultural objects. In 2003, for example, youth representatives from Tafalong visited the Museum of the Institute of Ethology at Academia Sinica to retrieve carved wood pillars for the rebuilding of the ancestral Kakitaan residence; a story told in scholar Hu Tai-Li’s documentary “Returning Souls”. At the end of 2014, Director of the NTU Museum of Anthropology Hu Chia-Yu and his staff visited Kaviyangan in Taiwu Township, Pingtung, asking to designate the four-sided carved wood pillar belonging to community leader Zingrur as national treasure. In 2015, the NTU Museum and Kaviyangan held a “wedding” ceremony to welcome to pillar to the museum. These examples show the trend of cultural property exhibitions moving beyond binary “return vs. not return” or “looting and looters vs. the looted” thinking.

Meaning and Retrospection on the Right to Interpretation

“Right to Interpretation” emphasizes a rethinking of the authority of knowledge production and the absence of indigenous rights to discourse. For his “Discovering the Pinuyumayan Community and Its Hunting Rites Indigenous Village Special Exhibition” held in Shung Ye Museum, scholar Chen Mao-Tai conducted a cross-analysis of the right to interpretation and texts on display, exploring indigenous people’s voice in the role of speaker. Chen indicated that even an indigenous presenter cannot guarantee an appropriate representation of culture.

Chen’s research involves the binary division of indigenous and non-indigenous interpreters. While Ku Hok-Bun maintains that anthropology of the past depended on in-person participation and faithful recording to legitimize the representation of authenticity of the Other, today, indigenous anthropology holds that “I grew up in” or “I ethnically belong to” provides the legitimacy to vocalize, represent, or claim factuality, as if culture is inscribed upon one’s DNA.

This new issue for reflection is “indigenous speaking up politics”. In the context of re-thinking the legitimacy of anthropological knowledge, traps and limitations of “indigenous” legitimacy appear. “Indigenous speaking up politics” generates legitimacy from closeness to fact, but also a myth that indigenous peoples are able to “imagine the Other.” Transcending the reflection of speaking up politics, the question becomes not whether the curator is indigenous, but the curator’s subjective stance, or from what perspective the narrative is created.

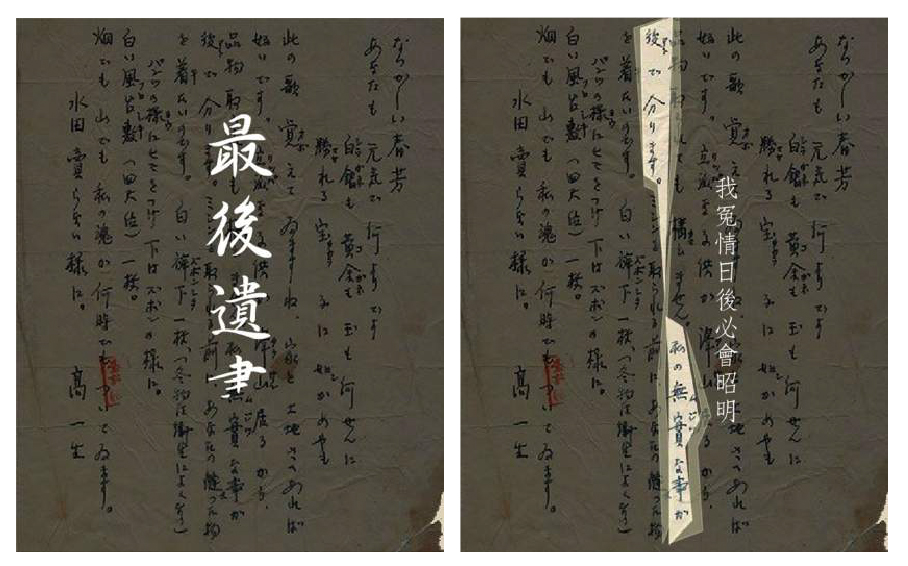

Gao Yi-Sheng was a political victim of the 228 Incident. His “Last Words”, written in Japanese, were adapted as short film for internet circulation.

Meaning and Retrospection on Ethnic Culture Exhibitions

The narrative or “genre” of indigenous exhibitions in museums is, for the most part, the cultural characteristics of ethnic groups. The core of such exhibitions is a showcase of different cultures including information about cultural objects on display and the costumed music and dance performances that highlight the beauty, characteristics, or achievements of a particular ethnic group. A narrative structure’s shared patterns and element combinations may be applied to different ethnic groups or communities. In other words, narrative patterns are roughly predictable, yet such predictability limits and restricts the creative development of narratives.

Exhibitions as such tend to focus on reconstructing cultural roots or local culture, which carries significance for disadvantaged indigenous peoples. However, from the viewers’ perspective, according to historian and anthropologist James Clifford, collective identity is often represented by a distinctive culture; for in-group members, symbolic cultural achievements are reinforced, but non-members remain bystanders.

Moreover, if this narrative genre remains the mainstay, indigenous stereotypes will become more engrained. Hence, under the premise of acknowledging the particular indigenous history and experience, the presentation of the retrospect of individual experience should not be limited to distinctive or stereotyped cultural characteristics; instead, exhibitions should integrate a historical perspective, such as exploring the changes through a community’s history or an individual’s experiences.

In 2003, the National Museum of Prehistory launched the special exhibition “Remembering Father’s Songs” in an attempt to shift historical focus from the group as a unit to the diversity and personal memories found within groups. This exhibition featured musicians Chen Shi (panTer, Minoru Kawamura, 1901-1973, Pinuyumayan), Gao Yi-Sheng (Uyongu Yatauyungana, Yata Issei, 1908-1954, Tsou), and Lu Sen-Bao (Baliwakkes, 1910-1988, Pinuyumayan). The changing language of their names, from indigenous to Japanese to Chinese, narrates changing political periods that each impacted these musicians’ lives and creations.

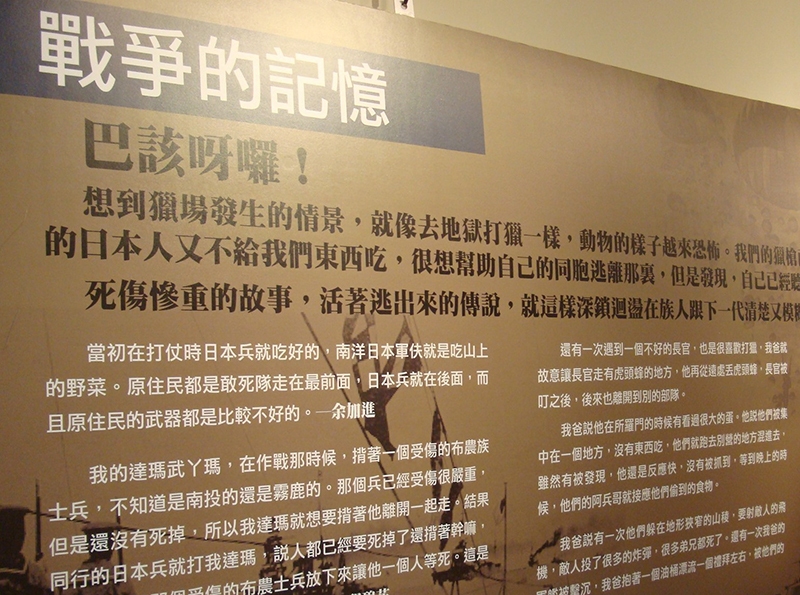

Special exhibition “Taupas, Japanese Army: Memories of Indigenous Soldiers Who Fought in the South Pacific” presents survivors’ memories during and after WWII, bringing this difficult chapter of Bunun history to light.

The Neglected or Simplified “Contact Zone”

The “Homecoming Exhibition” at the National Museum of Prehistory was a milestone in promoting the return of valuable cultural items to the source community for interpretation and exhibition. The landmark exhibition was “Kiwit Cultural Objects Come Home”, organized by the Kiwit Museum in Ruisui Township, Hualien, and the National Museum of Prehistory in 2009.

The National Museum of Prehistory and community figureheads emphasized engaging the community to select objects for display and to decide upon their interpretation. Li Tzu-Ning, then director of the museum’s collection management department, proposed a hitherto unused perspective - “contact zone” - to analyze indigenous curation. Cooperation between the National Museum of Prehistory and community allowed people from different cultural, political, and economic backgrounds to converse, sparking unexpected interactions.

The term contact zone was first proposed by art historian Mary Louise Pratt in 1991, and promoted in museums by James Clifford. Clifford pointed out that contact zone helps us understand that rigid social concepts like minority and community are connected to cultures and histories separate from the dominant society and unrelated to each other. A contact zone attempts to evoke the idea that colonizers and the colonized have intersecting and coexisting orbits, and the co-presence involves oppression and inequality.

Clifford’s notion of contact zone includes contact history and contact work, the former involving representations of culture on display, the need to recall struggles under colonial rule, and focuses on narrative, history, and politics. “Homecoming Exhibition” however, focuses on the contact work between the museum and indigenous communities and the advantage of holding rights to interpretation, emphasizing object interpretation and textual displays rather than colonial contact history carried by objects.

Robin Boast, Deputy Director and Curator for World Archaeology at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, pointed out that the 2000s saw unprecedented improvement as more museums empowered and embraced source communities. However, contact zones are often simplified as “dialogue” and “collaboration,” leading to the covering-up of historical and political issues that have not been fully represented. It becomes necessary, then, to reveal the dark and often unpleasant side of the contact zone.

The National Museum of Prehistory’s co-curation is a representation of the history contact of the colonizers and the colonized, yet contact zone is not included as a curatorial concept. In the museum’s collaboration with the Bunun Cultural Museum of Haiduan Township, for example, the special exhibition “Taupas, Japanese Army: Memories of Indigenous Soldiers Who Fought in the South Pacific” tells stories of indigenous youth mobilized to serve in the Imperial Japanese military in Nanyang and experienced the Chinese Civil War. The museum’s 2008 exhibition “Reassemble over Oblivion: The Tragically Heroic Cikasuan Battle” was a collaboration with the Shoufeng Indigenous Museum that presented stories from survivors of the 1908 Cikasuan Battle.

These two exhibition titles evoke colonial memories of trauma and separation - heartaches, tears, and dark historical shadows that can be addressed during the curation process.

In the 1990s, indigenous people created exhibitions featuring indigenous cultural characteristics in an attempt to seek cultural subjectivity. However, few texts representing social relations and colonial contact history were shown, and further consolidation of interethnic relations failed. The issue of right to interpretation should break from the antagonism between indigenous and non-indigenous groups and holistic concepts of community curation and indigenous perspectives, turning rather to the subjective positions and curatorial views of indigenous curators.

Special exhibition “Taupas, Japanese Army: Memories of Indigenous Soldiers Who Fought in the South Pacific” shows Bunun people serving in the Japanese Imperial in Nanyang.

This article is a summary of: Lu Mei-Fen (2015) Toward Text and Communication: The Changing Presentation of Taiwan’s Indigenous Peoples. Museology Quarterly, Vol. 29, Issue 3. Pages 5-36.

―References―

古學斌(2001)。〈誰掌真相之匙﹖次本地人類學者的一點看法和提醒〉,《文化研究月報》第二期。http://www.cc.ncu.edu.tw/~csa/oldjournal/02/journal_park_9.html。

李子寧(2011)。〈再訪‧「接觸地帶」──記奇美原住民文物館與國立臺灣博物館的「奇美文物回奇美」特展〉,《臺灣博物季刊》30(2):4-14。

陳茂泰(1997)。〈博物館與慶典:人類學文化再現的類型與政治〉,《中央研究院民族學研究所集刊》84:139-184。

Clifford, J.(1997). Routes, Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

Lu Mei-Fen

Lu Mei-Fen

Associate Curator of the Division of Exhibition and Education, National Museum of Prehistory, Lu specializes in museology and indigenous cultures, indigenous art, and indigenous culture policies.