Swirling ocean surrounding beautiful islands, the Tao is not the only indigenous people in Taiwan with a marine culture, the Pangcah, Kavalan, and Pinuyumayan all live alongside the ocean, and intimate connections with the ocean can be observed in their legends, diet, song, and dance, each with their individual unique Sea Ritual traditions.

Mikesi' at ‘Atolan Community, Fight to Defend the Sacred Place of the Community

Every summer, various Pangcah communities host rituals related to rivers and the ocean, including the sea ritual, river ritual, and fishing ritual. In addition to commemorating the hardship suffered by ancestors navigating the waters to reach Taiwan, and expressing gratitude to nature and deities for bountiful harvests, the preparation process of the ritual is an opportunity to train the age class to take part in public affairs in the community.

The ‘Atolan Community in Taitung calls their sea ritual Mikesi', and is held on the third day of the Harvest Ritual. On the day of the ritual, the young and mature age classes must dive into assigned waters to catch fish and shellfish via various fishing methods. Once ashore, the catch is calculated for score and shared among older people and various age classes as a symbol of sharing and respecting elders.

In the past, the ‘Atolan Community would hold the sea ritual in the location decided by community elders. In 2002, a tourist park was rumored to be developed in Pacifalan, but according to legends, it was where Pangcah ancestors first came ashore on this island, and also one of the locations sea ceremonies would be held. To defend the important sacred ancestral place, a series of protests began in the community leading to the building of the sea ritual hut at Pacifalan in 2005. The protests stopped the development for the time being, and the sea ritual has been held there regularly ever since.

Parunang, the Coming of Age Ritual Held Every Seven Years in Lidaw Community

Nanshi Pangcah is the utmost northern Pangcah group, among which, the Lidaw Community still practices the Parunang, Boat Ceremony, unique to the Pangcah. Legend has it that the ancestors of Lidaw Community traveled in 3 canoes and ended up on the East Coast. In memory of the hardship ancestors overcame in developing a new home, every 7 years, the community would hold the Parunang alongside the coming of age ritual for the age class.

The structure of the Pangcah age class is very strict, the male in the community begins receiving rigorous physical and skills training at the age of 12. After 7 years of training and upon completetion of the coming of age ritual, they can officially enter the age class organization in the community. The Parunang, held once every 7 years, in Lidaw Community is the last step to the coming of age ritual. On the day of Parunang, men who have just been promoted to the young adult age class will carry into the water canoes symbolizing the ones used by their ancestors, swim 15 meters away from the shore before swimming back, and once ashore, they will eat Bawsa, packed meal prepared by a female of similar age, thus completing the ritual.

Combining the parunang and the coming of age ritual not only relives the image of ancestors crossing the ocean to reach the island, but also symbolizes the new generation taking responsibility for public affairs in the community, and assuming the mission of building families to keep the community going with future generations.

Laligi at Paterungan Community, the First Sea Ritual Site Covered in Wave Breakers

Legend has it that the Kavalan crossed the ocean from southern islands, and was once active in maritime trade. In the 18th century, with non-indigenous peoples moving into the Ilan Plain, they uprooted and migrated east, residing along the Hualien and Taitung coast.

They left their ancestral land, but never forgot their connection with the ocean. Every year, as firey red Erythrina orientalis blooms in the early spring, signaling the season for flying fish, men in the community would start weaving fishnets and build bamboo rafts, and select a high tide day according to traditions to hold Laligi, the sea ritual. Laligi symbolizes the beginning of a new year and is an important ritual to the community. Widowers aside, all men in the community must gather at the estuary on the day, string together pig liver, heart, and meat, throw into the ocean and pray to the deities for bountiful harvest and safety at sea.

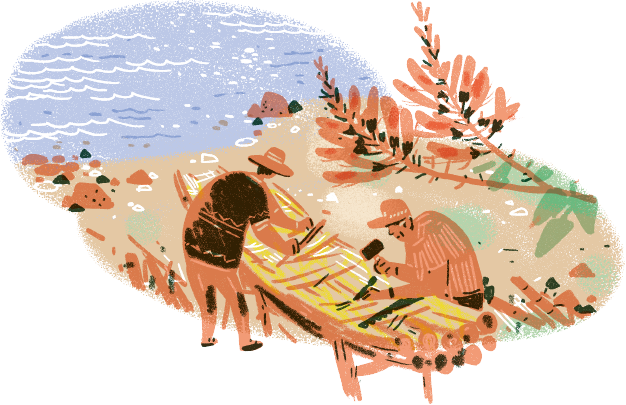

The Kavalan had once stopped holding the sea ritual and did not resume until they initiated the name rectification movement. The Paterungan Community resumed Laligi in 1996 and decided that Paterongan beach, the place where ancestors came ashore according to legends, shall be the first ceremonial site for sea ritual, and Xiaohu Chuanao the second ceremonial site. In 2016, the Hualien County Government installed concrete wave breakers along the beach of the first ceremonial site, protecting the coastline from sea erosion. Not only did it destroy the natural landscape, but there was no available path for their people to reach the water, and the original ceremonial site was also covered. After protest from the people and negotiations with the county government, the wave breakers were moved further ashore and a staircase leading to sea was put in, providing them a space for the sea ritual.

Mulaliyaban at the Sakuban Community, Worship Towards the North, East, and South Makes All the Difference

Once upon a time, the ancestors of the Pinuyumayan sailed overseas in search of staple food crops. Having discovered millet on Orchid Island, they took great pains in bringing the millet grains back to Taiwan so their people never had to worry about food again. In commemoration of the benevolence of their ancestors, every year after the harvest of millet, they will cook millet rice by the ocean as a way of worshipping their ancestors, and this is the origin of the Pinuyumayan Mulaliyaban, also known as the Millet Ritual.

There is another legend regarding the origin of the Mulaliyaban. Once upon a time, a naughty Pinuyumayan boy often played pranks on people, causing people grief, so when they went hunting on Green Island, they decided to abandon him on the island. When the boy learned that he was abandoned, he cried so loud that the deities took pity on him, and assigned a big fish to carry him back to Taiwan. The boy was instructed to prepare millet rice in the worship of the ocean after millet is harvested each year, as a way to thank the deities and the big fish for helping him.

With various sea ritual legends, the later generations worshipped in different directions towards the Orchid Island, Green Island, and Mt. ‘Atolan respectively. Nowadays, only the Sakuban Community still practices the sea ritual. The Rara and Sapayan clans worship in the direction of the Orchid Island at the estuary of the Pacific Ocean; the Arasis clan, being the descendants of the naughty boy, worshipped in the direction of the Green Island at Maoshan; the legend passed on by the Pasaraat and Palangatu clans was of the Mountain God wishing to eat freshly harvested crop once millet is harvested, therefore they worship in the direction of Mt. ‘Atolan at the north shore of Beinan River during the sea ritual.

On the morning of the sea ritual, men in the community would first gather inside the clan's ancestral spirit house before setting off to their individual worshipping locations, where they would build a make-shift grass hut and worship shed, cook the millet, and begin their worshipping ritual. The clans would meet to the east of the community after their ceremonies are completed, and return to the community together; in the afternoon, a series of celebratory events including wrestling, banquet, song, and dance would follow.

The sea ritual is closely connected to the traditional lives of these ethnic groups, an important medium shaping the collective memory of the groups. Influenced by the environment and lifestyle changes in modern society, the sea ritual of each group has suffered tremendous changes. In addition to the ritual being simplified and time shortened, its survival is also at risk due to the dwindling population in the community.

The ceremonial site for Paterungan Community and ‘Atolan Community have both once nearly disappeared due to public construction and land development; Lidaw Community has altered the running trails of their coming of age ritual and locations of Parunang many times due to changes in the environment and landscape; the tradition of worshipping in the direction of the Green Island during the sea ritual in Sakuban Community has discontinued, became no one in the Arasis clan can pass on the tradition.

Originally a male-dominated scene, some of the sea ceremonies held nowadays allow women to observe at the scene. Some ethnic groups combine beach cleaning and marine environmental education with their sea ceremonies, events conveying the modern concept of ecological preservation. This demonstrates that the sea ritual of indigenous peoples is more than just a spiritual belief, but a complete system of marine knowledge comprising of traditional skills, social relations, ecology, environment, and more.

—References—

蔡政良(2020)。〈東海岸阿美族海祭的社會與生態意涵〉,《海洋探索》試刊號。

李宜澤(2020)。〈祭儀地景的多重記憶與環境偏移:南勢阿美族里漏部落船祭活動變遷與文化製作〉,《民俗曲藝》,第210期。

趙守彥,〈新社部落噶瑪蘭族海祭〉,《數位島嶼》,https://cyberisland.ndap.org.tw/graphyer/album/etok。

宮莉筠(2020)。〈看不見的海祭場〉,《原教界》第96期。

法物嘞(2016)。〈消波塊海堤工程 新社族人痛批破壞自然〉,原住民族電視臺,http://titv.ipcf.org.tw/news-22604。

陳耀芳、林素珍(2020)。〈噶瑪蘭族立德(Kodic)部落文化的維繫-從立德部落海祭觀察〉,《現代桃花源學刊》第9期。

〈卑南族傳統文化〉,國立臺灣史前文化博物館,https://www.dmtip.gov.tw/web/page/detail?l1=2&l2=61&l3=434&l4=448。

林娜鈴(2014),〈普悠馬(南王)temararamaw的傳承與存續〉,國立臺東大學南島文化研究所碩士論文。