27 years have passed and the young man who rode his bike all the way from Taipei to ‘Atolan now has already become a member of the indigenous age stratum that actively engages in community affairs. He documented and preserved indigenous culture, and promoted community autonomy and branding. Futuru set his mind to carving out a better future for the cultural continuity of his community which enthralled him years ago.

Known for its sugar factory and surfing destination, ‘Atolan means “a place with many rocks” in Amis, implying that Amis people have settled here for generations. Nestled between mountains and the sea, the rich natural resources have shaped the culture of this indigenous community which has been passed down from generation to generation. However, after the 1970s, urbanization started to drain local population, tearing a cultural gap in the community. The absence of generations of people forecasted a crisis of the community culture continuity.

In 1994, a Hakka young man from Hsinchu, Futuru Tsai rode his bike alone and arrived at ‘Atolan for short-term field observation. He cycled toward south along the eastern coast. “I rode past Marongarong Community and they were performing traditional ceremony. There were many teenagers and they looked exhausted as if they were overworked. But when I got to ‘Atolan, there were no teens at all.” That observation became a turning point. From that point on, Futuru dedicated the later half of his life to ‘Atolan

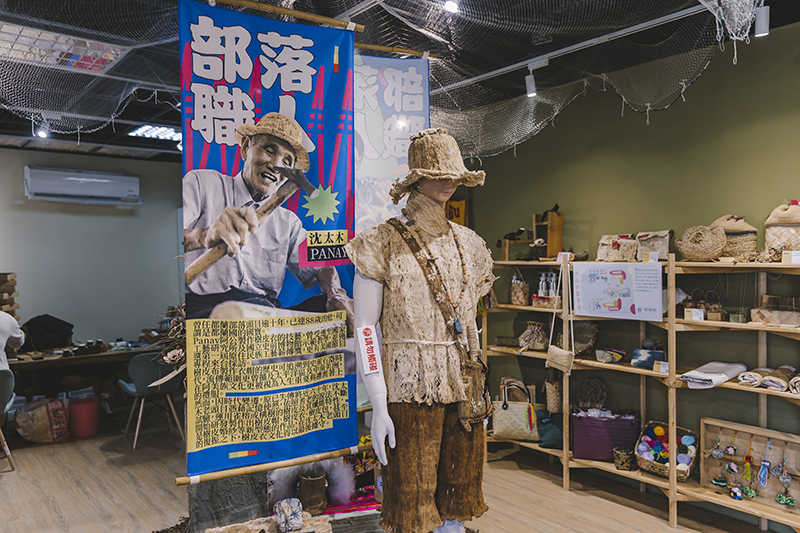

Futuru and his fellow community members founded ‘Atolan Style together with the hope to offer the general public easier access to indigenous life and encourage visitors to explore ‘Atolan.

Restoring the Tradition of Pakalongay

and Showing a Path That Leads Teens Back to Their Community

Maybe it is his easygoing personality or just destiny that got him invited to the age stratum of the indigenous community as an outsider after a short period of his field observation. “I did not know that joining the age stratum means you stay for life. And I am grateful that the community took me in as one of their own.” Futuru said with a smile. When he joined this indigenous community, he became a member of a big family. Futuru’s age stratum decided to restore Pakalongay, the youngest group of Amis age-based social structure.

Therefore, Futuru, director Lin of Dulan Junior High and other like-minded community members traveled between north and south to recruit young people to return home and pick up traditional knowledge. They designed the curriculum and teaching materials which covered knowledge like wild plant collection, tool making, traditional tunes and dancing and applied modern summer camp model to train Pakalongay before the traditional ceremony took place. “Many elders shed tears upon seeing more than 40 teenagers showing up on the ceremonial ground,” Futuru recalled.

Since the first edition of the Pakalongay training camp, teenagers have been holding hands and participating in the voluntary training program before annual ceremony year after year for more than two decades. The fostering of Pakalongay is a long term process during which they explore mountains and the sea together to learn about nature while taking care of each other. In addition to one-off events, the next step toward restoring community engagement is to bring people back to nature.

‘Atolan Style presents ‘Atolan as a place where Amis people call home and shows their daily lives, giving visitors an authentic 'Atolan experience.

Sea is the Path

to a Human-Sea Connection

“Sea is more than a space. It is a living organism.” Futuru observed that Amis culture sees sea as a being with spirituality and vitality. Also the sea is not a separate feature of nature; instead, it is a part of the ecosystem also consisting of land and rivers.

Amis language indicates their body of knowledge derived from the sea and rivers. “For example, the names of creatures in the sea correspond to that of the land. There is wild boar on land so there is wild boar in the sea; there is grasshopper on land, so there is also grasshopper in the sea.” Futuru gave an example: Acanthurus lineatus, or commonly known as striped surgeonfish is called riri’ in Amis, meaning grasshopper, because the fish is usually spotted fast moving in the wave zone, just like grasshopper.

Plectorhinchus lessonii is called Kakita’an no foting (or mitilidan ni Diwa) in Amis implying that the fish is like a community leader: they always come in pairs and bring along other fishes, benefiting Amis people. The name also has to do with the pattern on its body. Amis people believe the colorful pattern is a gift from sea god Diwa.

However, the Amis names of these fishes have gradually vanished from the vocabulary of those under the age of 60. In light of the problem, Futuru constantly went diving in order to learn from fellow indigenous divers. He also worked with the community to produce teaching materials and write books to preserve these names. However, armchair reading is not the way to learn culture, you have to be there. In recent years, Futuru would dive with fellow members of his age stratum, encouraging younger community brothers to return to the sea by setting an example through his actions.

Photo credit: ‘Atolan Style

Photo credit: Mark Chu

Diving and fishing are the essential skills that ‘Atolan men have to acquire.

Showcasing the Sea and Land,

‘Atolan Style Explores a Way Forward

For more than two decades, Futuru took part in the restoration efforts like bringing young people back home, back to diving, and documenting culture. However, they also realized that it would take more than the community’s efforts to accomplish their goals. Surrounded by the sea and mountains, the daily routines of Amis people reflect immediately the changes of the natural environment. When the mountains and the sea suffer irreversible destruction, the community would also lose their means to foster good bond between the members of age strata and pass on their traditional knowledge about nature.

“Indigenous people have lost too many things under the oppression of the mainstream Non-indigenous society.” Futuru then explained that in terms of system, the indigenous community is not a legally recognized autonomy. The current legal framework only allows a community register as a juridical association where the community leader serves as chairperson. However, those that matter the most-marine resources, land development, ecological environment- are beyond the control of the indigenous community. This is why indigenous people want to fight for autonomy and sovereignty. “But on the other hand, indigenous people have never signed any treaty which surrenders their sovereignty to the state,” Futuru said with a dry laugh.

Being excluded from the decision-making circle does not mean that the community has given up on their rights. For instance, seeing the decrease of marine resources in the ‘Atolan’s territorial waters, the community began to discuss about their approach to marine conservation since 2020 and developed internal self-regulation guidelines. The community also has worked on the legalization of these rules. “It’s like our refrigerator broke down so we are trying to fix it.” In addition to the issue of marine resources, Futuru also added other examples. Pollution caused by the use of pesticide to eradicate of apple snails and the cultivate custard apples on land also impacted the natural environment on which indigenous people depend for their livelihoods. “We still need to negotiate with parties like the county government, fisherman’s association, and Non-indigenous people. There is still a lot of work to do going forward.”

Goals like cultural continuity and the establishment of indigenous autonomy can not be accomplished overnight. Futuru and his partners have never given up on any possible solutions. ‘Atolan Style is their latest attempt. Advertised as a community-owned corporation, ‘Atolan Style runs a diversified business, offering local agricultural produce, tours, professionally selected products on an indigenous-oriented platform. The brand will give the public the opportunity to better understanding indigenous people and community under the wave of emigration and tourism. ‘Atolan Style does more than allowing young people to return to the community. Its proceeds will also be invested back to shared community affairs, supporting members of the community.

To better introduce to the general public indigenous culture, the indigenous community organized sea culture experience tour to give the general public a taste of indigenous lifestyle. Photo courtesy of ‘Atolan Style