A young indigenous couple moves to Taitung’s Tomiyac Community to conduct field research for their theses. They spend a year befriending and establishing relationships with local elders who now treat them as if they were their own children. The couple chooses to stay and settle down with the ideals of preserving and passing on the village’s unique culture by keeping a record of local life.

Boasting an unimpeded view of the vast Pacific Ocean and endowed with numerous unique landscapes made by the movements of the earth’s crust, Taiwan’s east coast is lined with famous scenic spots that attract visitors for sightseeing all year round. Near the Stone Umbrella Scenic Area, a popular tourist attraction of Taitung’s Chenggong Township, sits a young indigenous community: the Tomiyac Community, which was established by Amis migrants from Hualien’s Rift Valley area 130 years ago.

The community has a population of over 700 people, but the number has been reduced because of severe population outflows. Currently, it is inhabited by merely 100 households or so with some elderly people living alone. Yet in recent years, this aging community, hidden quietly nearby the bustling tourist attraction, has been joined by a young couple who have set down roots and never given up the dreams of attracting more youths to return to learn about their own culture.

Thanks to the rich diversity of marine species in the intertidal zone, tools and methods for harvesting vary greatly, depending on the accumulation of collective experience and knowledge about the sea.

Reflecting on the Meaning of Indigenous Culture After Growing Up

The couple is two Amis youths: Uhay Putul, a girl hailing from Hualien, and Oseng Kuhpid Cuper, a Tomiyac-born native. Born in the Ci Alupalan Community of Hualien’s Shoufeng Township, Uhay moved with her family to the Fakong Community in Fengbin Township, where she grew up surrounded by “sea and seafood,” as a child because of her father’s work. As she recalls, her father would often take the family to the beach on weekends, when she’d see many local ina (“woman” in the Amis language) gathering ingredients in the intertidal zone. “Every time we visited friends as guests, all the dishes on the dining table were cooked with ingredients collected from the sea.”

Unlike Uhay, who grew up in an environment closely connected to nature and indigenous culture, Oseng was born in Tomiyac but raised in Taoyuan, where most of his peers were from mainland Chinese families before he went to college. “As a child, I was aware of my indigenous identity, but I was so concerned about how my peers might look at me that I’d deliberately speak with big words and perfect pronunciation of retroflex sounds like Chinese mainlanders do. That’s why Uhay likes to tease me by calling me a ‘damned mainlander,’” says Oseng with a laugh.

The young couple, despite their completely different backgrounds, is attracted to the Tomiyac Community by a shared desire to understand the root of their culture. While in college, Oseng met a group of indigenous friends who were enthusiastic about promoting indigenous cultures. He was thus inspired to think about what he can do for indigenous communities. Uhay, on the other hand, was inspired by the shock she experienced while working in the Formosa Aboriginal Singing and Dance Troupe, which sparked her interest in exploring the indigenous culture. “I like who I am as a member of Taiwan’s indigenous community, but to be honest I don’t know quite much about my culture. It wasn’t until I got to understand the historical context behind the music and dance meticulously choreographed by other senior performers that I truly realized what it means to be ‘indigenous.’”

Occasionally, Uhay would work with the village elders in the intertidal zone to acquire knowledge about gathering and document it by filming.

Lifelong Quest for Knowledge about Intertidal Zone Harvesting

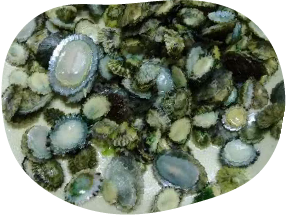

Having lived in the Tomiyac Community for nearly 5 years, Uhay considers herself still a beginner in terms of harvesting skills. She divides intertidal zone harvesting practices into three levels based on the difficulties of gathering. The main target for beginners is shellfish that live on rocks, such as cekiw (grata limpet), which would surface at low tide and are easy to spot and catch. Seaweed like kakoton (carrageen moss) is also accessible, but collecting it is a challenging task. This is because it grows on rocks within reach of the waves, which requires one to take advantage of the timing when the waves recede. “We do it in a cycle of five waves. The first three ones are larger, and we have to approach rocks at the accurate timing as the third wave begins to recede and rush back before the next big wave comes. So it requires at least two persons to team up for the task, with one observing the changes in waves and sea conditions,” Uhay notes.

The intermediate level requires one to swim from one location to another as some targets live on coral rocks offshore, while the highest level involves diving 3 to 4 meters into the sea to collect seaweed and shellfish living down below. “I’m not good at swimming, and that’s why I am always a beginner and never upgrade to a higher level,” says Uhay laughingly. But even for beginners, there are many things to learn about the sea and how to deal with their catch. In addition to collecting, one must be able to identify the wide variety of sea creatures that can be harvested in the intertidal zone. And it is a whole field of learning regarding how to deal with these ingredients, and when and where to eat them.

Take cooking cekiw. To begin with, one has to rinse the shellfish in water, then blanch them quickly in boiling water with a sieve. When they’re cooked, add a sprinkle of salt, and the dish is ready to serve. Other shellfish, like pe’coh (barnacles), are used by locals to make soup. Sometimes seaweed is added to create a rich flavor. In most seafood restaurants, though, they are usually grilled. The seaweed that grows on sand is more trouble to prepare. Upon harvesting, it must undergo several rinsing processes both at the beach and back at home, until it’s clean of sand. Then the processed seaweed must be stored in the freezer before cooking.

As every living thing has its own lifecycle, the target of harvesting varies greatly from season to season. For example, the main catch at the junction of spring and summer is shellfish, which would come in abundant varieties in the summertime. During fall and winter, when the seasonal northeastern winds pick up, harvesting activities are suspended. This is the time for people to rest and for the ocean to recover. When spring comes, the season of collecting seaweed begins. “Seaweed collecting must be done at low tide, and the harvesting season only lasts until the end of April. Afterward, the weather will get so hot that seaweed is liable to be dried up by the sun,” Uhay explains.

In general, there is a regular pattern of seasonal harvesting in the intertidal zone, it’s not a golden rule that must be followed, though. “It’s like calling friends out for playing basketball as casually as we normally do, which depends on the mood and weather of the day. If it feels right, the weather is fine, and waves are good, we’ll go out to the beach together.”

Be a Bellwether

Despite its vicinity to the sea, the Tomiyac Community does not have taboos or distinctive sea rituals like other Amis communities do. Oseng thinks this could be attributed to its historical background in that the Tomiyac Community relocated from Hualien’s Rift Valley to the seaside township of Chenggong for the sake of livelihood. Their purpose of migration is to seek more resources for living, and therefore the village has a different concept of “taboos.”

Despite their lack of established ceremonies or rituals to celebrate, the Tomiyac people are endowed with knowledge passed on by the elderly about the environment they live by, through which a tacit agreement between humans and nature has been established. “The village elders know immediately that a certain kind of shellfish will be lacking upon seeing the depletion of certain seaweed it feeds on. When detecting changes in the environment, like spotting symptoms of illness, they know it’s time to change to another location for harvesting to let the land rest and recover.” Oseng explains that due to its short history and influence of foreign religions, what the sea ritual means to people here is more symbolic than substantial. “We base our harvesting practices on the respect for the environment and its ecology we live by,” he concludes.

The Tomiyac Community owes its unique marine culture to its obscurity that prevents the interference of tourism, which enables its culture to remain completely intact. Yet this also becomes a major driving force that propels young people out of the community. “As the village is unable to develop its own industries, young people who move away from home are liable to be affected by the mainstream culture, failing to appreciate the value of their hometown. That’s why we decide to play the role of a bellwether to attract more people to come back,” says Oseng.

With a shared purpose of getting close to their root, the couple takes different approaches to recording and preserving Tomiyac’s indigenous culture, with Uhay focusing on acquiring the knowledge about intertidal zone harvesting and Oseng emphasizing land issues. Their research happens to constitute a complete system of the community’s traditional knowledge. The couple set up a studio and name it “831” after their house number. By doing so they intend to make it a reminder of Tomiyac as their starting point and mark their first step toward achieving their ideals by recording local stories and passing on the village’s culture.

pe'cho

cekiw