The ocean environment in Palau boasts of the most diversified coral reef ecosystem in the Micronesia archipelago, it is also the international biodiversity hot spot between Polynesia to Micronesia and sits at the heart of species survival globally.

For the longest time, Palauans have prohibited fishing during the reproduction and foraging periods to maintain ecological balance. This method has now been broadly applied to cover the majority of the country’s exclusive economic zone. In 2015, the Palau government adopted a law to set up the Palau National Marine Sanctuary (PNMS), which was officially launched on January 1st, 2020. The Palau government has closed 80% of their Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and banned all fishing and marine resource gathering activities, while the remaining 20% of the EEZ is reserved as Domestic Fishing Zone (DFZ) in support of local food security and economic opportunities.

This extremely “advanced” ocean protection project combines traditional conservation ideas and scientific knowledge of ecology and is built on the existing Palau Protected Area Network (PAN). They have in recent years collaborated on the Pristine Sea Project with the National Geographic Society to evaluate a marine protected area, then engaged in collaborative research with Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions before executing the project in 2020.

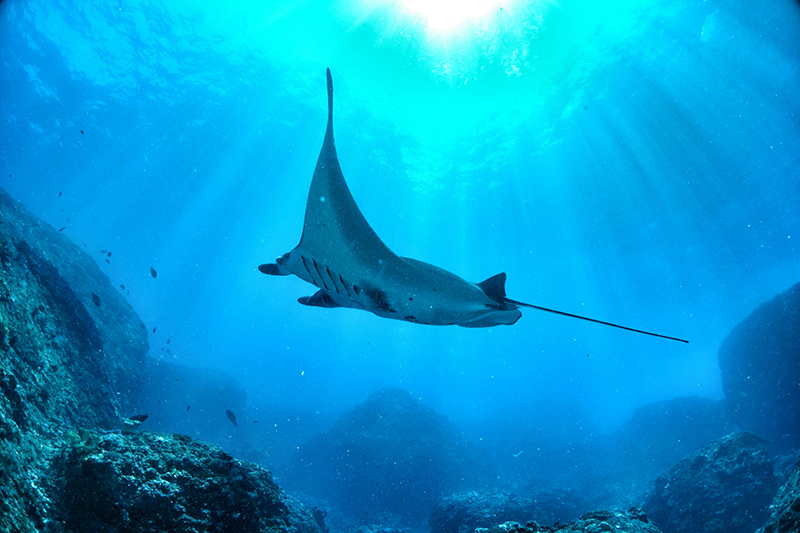

Giant oceanic manta ray in the waters of Palau.

bul, the Traditional Ocean Governance

Prior to being ruled by western countries, traditional leaders and their kinship had the customary marine tenure in Palau. Customary marine tenure is defined as “a special group with official or nonofficial rights to the coastal areas, and according to customs, their right to use and access to marine resources is exclusive, transferrable, and mandatory.” This definition includes bul (meaning restrictions, as in temporary cease of fishing or gathering) and religious taboos in the Palauan concept. Violation of such principles or taboos will lead to punishment, exile, humiliation, or even death by execution, such cultural practices also maintain the sustainability of marine resources.

The Spanish first colonized Palau in 1885, followed by Germany, Japan, and the US. During the Japanese and US ruling periods, the introduction of their legal and economic systems weakened the power of traditional ocean governance, fishing became open to all without restrictions, and hence the reduction of fish stocks over the years. Palau declared independence in 1994 but is still politically tied to the US government, the Palau federal government also continues to adopt the American political system including bicameralism, respective constitutions for all 16 state governments, and state governors are legally elected; the national constitution also grants local governments powers including the power to enact and execute laws. All state governments incorporate traditional law in their local government system, which causes tension between the execution of traditional law and statutory law. Such tension is also reflected between the traditional leader and elected leader, and further extended to the governance of marine resources.

Throughout the entire 1990s, traditional leaders, state governments, and the nation fought over control of marine resources. Later, the court supported the nation’s right to establish and execute regulations regarding the use of marine resources, giving users of such resources (various state governments) a high degree of autonomy and the right to establish a collective decision-making mechanism and rules regarding marine resources.

Palau is determined to preserve its natural ecology, so human destruction is rarely seen along the coastline.

The Essential Concept of the Multi-Centered Governance of bul

In the 1980s, various state governments actively executed their right to manage their resources, and by the mid-1990s to early 2000s, almost every state control fishing activity via the practice of bul and establishing the Marine Protected Area (MPA), the Palauan government collectively named bul and MPA as conservation areas. In 2003, there were at least 26 conservation areas in 13 states, and starting in 2007, every state has at least one conservation area.

According to the collective decision-making mechanism then, the power to establish rules regarding the conservation areas was given to chiefs and state governments. In some cases, the co-management commission includes traditional leaders, the state government, and community members, NGOs are allowed to take part as well. The rules managing the conservation area all vary, mostly including rules regarding borders, surveillance, and conflict-resolving, with different levels of sanctions from humiliation, penalty to incarceration. The high degree of local self-government then led to a multi-centered and individually planned management of the conservation areas.

With marine ecology recovered, animals can often be seen along the coast.

Create a Multi-Centered Decision-Making System through PAN

In 2003, Palau drafted the Protected Area Network (PAN) Act. The main concept is proposed by Palauans/non-Palauans, and they wish to develop a science-based national protected area network to maintain marine biodiversity. With structural reform, relevant authorities within local conservation areas are included in the new national authority, and in doing so, some local administrative power is transferred to the central government. The legitimate reason for this power transfer is to maintain the natural status of the ecology, therefore the scale of conservation areas must be expanded.

There were two forces pushing for the establishment of PAN, one was the mass whitening of coral reef in 1998 which raised public awareness on the threat of climate change. The public believed that to maintain the continuity, expression, and resilience of the ecology, a larger scale of protected areas is required, instead of the individually managed conservation areas demarcated by each state. Ecological continuity became the first priority of conservation, in turn facilitating structural reform while achieving the redistribution of decision-making power. Secondly, in response to the 2002 Convention on Biological Diversity, the nation began providing financial support, and through the originally multi-centered management, PAN covered conservations areas across state borders, making the nation and NGOs the main opinion leaders instead and thus enabling a more centralized decision-making mechanism.

However, state governments were worried that they would lose ownership of their conservation areas and also concerned that they have no resources available to sustain the operation of PAN, so no member signed on to join the PAN from its enactment in 2003 until 2008. In 2008, the Palau government amended the Act ensuring the ownership and management of state governments. By creating a Management Council, the roles played by the nation and NGOs are restricted, giving official power to resource users, including the power to make comprehensive planning and system management projects, and resource users are all entitled to raise opinions and make decisions. Meanwhile, an amendment was also made to collect a $15 USD Green Fee from every visitor starting 2009. The amendment eased the concerns of various state governments and joined the network one after another. With PAN leading the structural reform, the basic multi-layered co-management model in Palau gradually took shape and showed the world that a collaborative network is only possible when local authorities have the power to make their own decisions.

Establishment of the Palau International Marine Sanctuary

In 2015, the Palau government planned to establish the Palau National Marine Sanctuary (PNMS) by 2020, with the duty of operation shared by the Palau Ministry of Natural Resources, Environment, and Tourism, Ministry of Justice, and International Coral Reef Center. The former two authorities are responsible for establishing administrative rules and providing legal support, while the latter is responsible for scientific research and education campaigns.

Economic income in the area will support the operations of various organizations in Palau, including fishes caught within restricted areas taxed if exported, and every inbound visitor is charged a $100 USD Pristine Paradise Environmental Fee upon entry at the airport.

Global warming is increasing affecting the ecological environment of island countries. The reason Palau is able to establish such an advanced marine protected area is not only because of bul, the Palauan traditional knowledge, but also because PAN has laid the foundation for multi-layered cooperation. With integration and pooling of resources, external resources and scientific knowledge is combined with planning and management and becoming the key capability to combating the critical challenges posed by climate change in the world today.

—Refrences—

Rebecca L. Gruby, Xavier Basurto (2014). Multi-level governance for large marine commons: Politics and polycentricity in Palau's protected area network. In Environmental Science & Policy 36 (2014) 48–60.