Accompanied by the owner of the brick kiln*, the group sets off to the mine in Sado Community to collect the soil. The site is an indented pit, “the pit is indented due to the decades of soil collected by the brick kiln to make bricks, which also means that the soil we now collect is closer to the surface of the earth, making it stickier and purer,” says Afo’.

*The site they are collecting the soil from belongs to the brick kiln, and the owner allows Afo’ to collect the soil that she needs to make potteries. Each time she collects the soil, Afo’s invited the owner to be present.

Prior to collecting the soil, we must first pray. Afo’ prepares two cups of rice wine, 3 pieces of betel nuts, and 3 cigarettes, and in the Pangcah language, she explains to the spirits of the sky, the earth, the mountain, and ancestors why we have come here, and that in so doing we mean to pass on the wisdom of ancestors, please do us no harm. After she finishes praying, Afo’ dabs at the rice wine with her finger and flicks it in three directions. She then lights the cigarettes, fixes them onto the grass blades, and waits for a little while before pouring the rice wine into the soil.

Only after the entire praying process is completed do we start shoveling to collect the soil, and even then, we only take the estimated amount necessary to make the potteries. Having bagged the soil, on our way back, Afo’ gives us each a pebble and reminds us to recite our name after we have exited the mountain, say “we are going home” and throw away the pebble. “This way, spirits in the mountains will not follow us home,” adds Afo’.

The previous generation collected soil from the Atomo Community, from collecting, drying, and sifting the soil to finally burning the pottery, every step was completed on the plot next to Afo’s house. They later switched to Sado because the soil there is even better for pottery making, and that is where the brick kiln extracts the soil they use.

After the soil collected is dried out, clumps will form, the dried soil must be laid out on a flat surface and hammered into tiny pieces. Before there were hammers, they used river rocks to smash the clumps, therefore every household had rocks stored specifically to smash the soil clumps with!

Once the soil clumps have been smashed, the impurities within the soil are revealed, which are usually foreign matters including grassroots, fallen leaves, and shells. Filtering out the impurities can be easy but extremely time-consuming. If the foreign matters are not filtered out at this stage, when the shaped clay expands during the heating process, the foreign matter will cause the piece to crack and sometimes even jeopardize the other pieces. So, this must be handled with care. In the old days, the elders would sit together and go through the soil together, and whatever they cannot finish on that day, they will pick up the next day. After the impurities are filtered out and all that is left is just soil, a sieve* is used to make sure the soil is clean, leaving only the finest sandy soil.

*The sieves used to be bamboo woven.

Filtering out the impurities was the only process elders allow children to take part in. Afo’ recalls helping as a child. But once the impurities are filtered out and grownups have begun processing and shaping the clay, the children are shooed aside.

However careful you sift, something will always fall through the cracks, therefore the elders would make two items of the same vessel just in case one cracks. After all, if the pottery fails, one will have to handle a whole year without a stock pot and that would be a problem.

After the soil is sifted, it is processed. Make a hole in the middle of the soil mound and pour in water. The water must be added slowly, too much moisture will not do. It is entirely up to experience how much water to add, and you decide by feeling the soil with your hand. The soil and water are mixed and slowly kneaded into a ball of clay. After the clay ball is somewhat firm, the clay ball is pounded with a beer bottle or tossed up and down with the hands to make it smooth and firm.

In the beginning, small pieces of clay dirt will stick to the palms, but as you process the clay, the bits will gradually form a clump. When the pores in the clay ball become finer and finer, and the ball no longer feels sticky, or when a slight touch at the clay ball can smooth out the crinkles on the surface, it means the clay is well processed and ready to be used as potting clay. To make larger pieces, river sand can be added to increase stability and prevent the pottery from violent contractions, making the pottery more firing tolerant.

If the potting clay is not to be used immediately, it can be stored in a zipper bag* to keep it moisturized. Foday explains that it’s like culturing the clay, clay balls that have sat for a while are much easier to handle. He usually keeps some for spare as well.

*Traditionally they would wrap them in banana leaves.

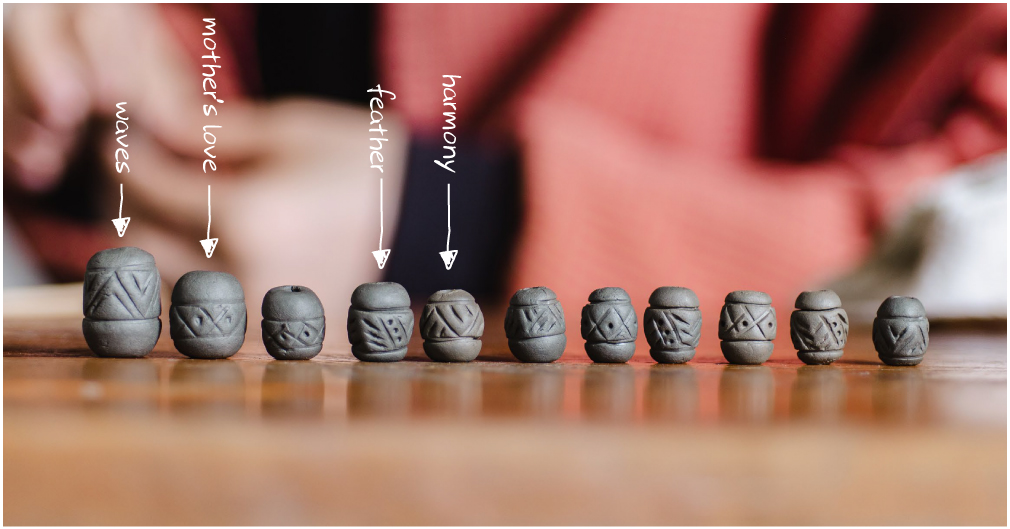

First time shaping, Afo’ had hewen start from small, a “ceramic bead”. The practice ceramic bead is about the size of a phalange. It can be shaped into a spindle, a sphere, or a stripe, or wrapped around the stem of a leaf to make a curvy bead with the arc of the stem, just as she prefers. These ceramic beads can be made into accessories such as necklaces and bracelets.

Afo' demonstrates.

Take an appropriate amount of clay from the ball and knead it with both palms to make the desired shape before carving onto the bead a pattern with a tool. Using tools such as straw, ball pen, bamboo skewer, and blade, Afo’ also taught her a few traditional Pangcah patterns which stand for waves, mother’s love, feather, and harmony, so that hewen can carve onto her own ceramic beads.

hewen's work.