The Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj is said to be the first to have a state system among Austronesian; its scope of area covered south of the Central Mountains and it successfully resisted the attack of the Netherlands military. But, like other political sovereignties in Taiwan in the 17th Century, this Kingdom was invaded and assimilated by foreign powers and gradually collapsed. Now, with the effort of the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj group, the footprints and glories of the Kingdom are found only in scarce literary records and oral investigations.

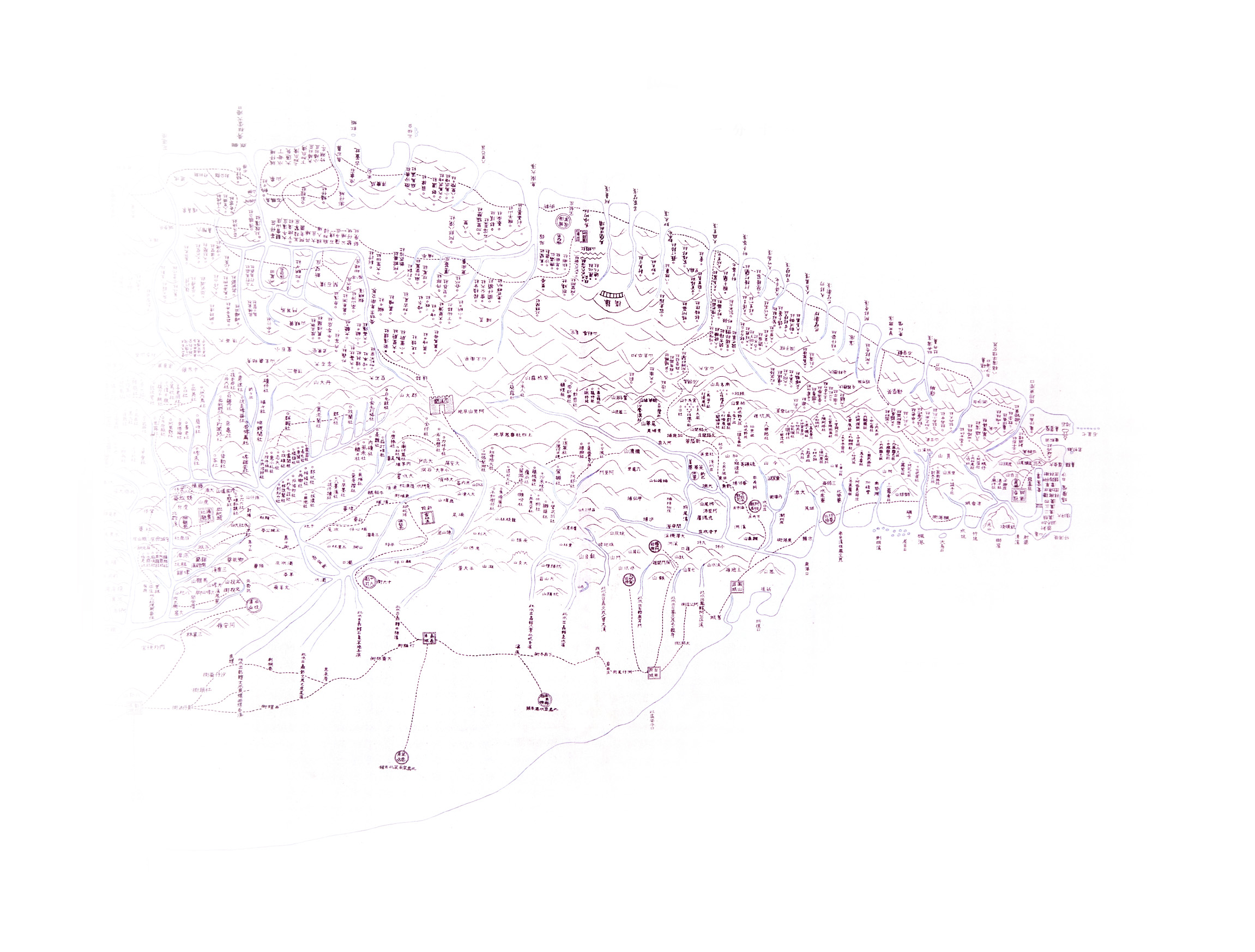

Taiwan Barbarian Map, inside front 《臺灣原住民族歷史地圖集》, SNC Publishing Inc.

“The Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj was ruled by the Paiwan people since the middle of 17th Century when it began its written records, and it was the first organization with a state system among the world’s Austronesian people.” These are the words of the contemporary well-known US scholar and historian on Chinese studies Tonio Andrade, about the Kingdom. This passage indicates the extremely important historical significance of the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj on Taiwan and Austronesians. How did the Kingdom develop and why was it named as “a kingdom”, and how did this Kingdom interact with other powers?

To unveil the mysteries of the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj, as shown in presently preserved literature, we need to trace back to the middle of the 17th Century. In 1624, due to competition under the Era of Discovery, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) sailed and arrived in Taiwan and began the Netherlands era on Formosa. According to Netherlands literature of 1638, Tjaquvuquvulj was originally pronounced “Tocobocobul,” but was later changed because of the differences within interpreters’ pronunciation and recorders. It was then pronounced as Tacabul, Taccabul, Tockopol, Tokopol, and Takabolder.

In the Qing Dynasty it was referred to as “Tjaquvuquvulj,” and in the Japanese ruling period it was called “Neiwen.” The National Government continuously used the name. Although it was called different names at different times, it is now commonly referred to as “the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj,” as an attempt to restore its cultural history.

About 400 years ago, the once prosperous Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj was located South of the Central Mountains ruled a very large area which included today’s area south of the Shuimang River to the North of Fonggang River, comprising about 23 indigenous communities. However, with political power shifts, wars, and killings in Taiwan, the Tjaquvuquvulj culture and history was suppressed and cultivated through “civilization” and disappeared. It is a pity but fortunately, a handful of text records in different political ruling periods were left for its people to trace back their historical origins.

The Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj

Jointly Ruled by Two Kings

Generally, the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj was thought to have the initial formation of a state, because it had its own land, people, sovereignty, and government, matched with the less restricted composition elements of a state. If we adopt a stricter academic theory, however, it had the political structure of a confederation, a social order and a political unit. Its social order is composed of a family community or a family system. The social development initially had class ranking and labor division, but strictly speaking it was not developed as a state.

Unlike other kingdoms, the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj’s ruling power was not limited to an individual leader. Instead, it was ruled by two leading families with shared political power, possessing the characteristic of “joint rule by two kings.” The two dominating families were respectively from Ruvaniyau and Tjuleng communities. With cooperation and competition, they gradually ruled their people jointly and co-defended common enemies to attract neighborhood communities to pay tributary and seek protection. Therefore, the autonomous confederation was built. According to researchers, about 23 indigenous communities or Non-indigenous communities sought to be governed, indicating the greatness and prosperity of the Kingdom.

Basically, the lands of the Kingdom all belonged to community leaders who were at the core of Paiwan society. Additionally, there were statuses of hereditary classes such as community escrows, families, and priests who assisted leaders in the operations of the confederation. The confederation leader internally governed political, cultural, religious, and financial affairs under his administration, and externally declared wars, peace -making, and contracting, in the same manner as a king or leader in a feudal society.

Wars, Migration

and the Rise and Fall of Tjaquvuquvulj

We are not able to clearly ascertain when the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj began, but according to contemporary academic research on historical literature review and field studies, the Kingdom existed in the 17th Century and then migrated to mix with local ancient Paiwan, Cimo, Pinuyumayan, Orchid Island, and Xiaoliuoqiao peoples.

In 1624, the Netherlands launched its oversea colonial headquarters to settle in Southern Taiwan, marking a new chapter in Taiwanese history. Since then, foreign civilizations have interacted with Taiwan’s indigenous peoples on a large scale systematically. The history of the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj was reshaped and the fate of Formosa was changed.

During Netherlands rule, the VOC attempted to get close with indigenous people to control the Non-indigenous people, obtain control, and acquire more resources in Taiwan. It invited community or confederation leaders to attend local meetings and authorized ritual symbols to encourage surrender. The Netherlands desired to further develop resources on the island and planned to explore the gold mines in Lonckjau (Hengchun Peninsula) by contacting the indigenous peoples in that area. The Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj belonging to the Up 18 Lonckjau Communities area was not willing to surrender and kept a distant relationship with the Netherlands. Later, it cooperated with communities discontented with Netherlands rule and became stronger. In1661, the Netherlands sent their military to attack the Kingdom twice, and the peoples of the Kingdom fled to the mountains and valleys and fought back to defeat the Netherlands military. The Netherlands’ defense capabilities were diminished and that indirectly resulted in Koxinga’s success next year in his military attacks on Taiwan.

In 1683, the Qing Dynasty defeated Zheng Ke-shuang and began its 212-year rule of Taiwan. During this period, a huge number of Non-indigenous people continuously arrived in Taiwan for settlement, resulting in more conflicts between the Non-indigenous and indigenous peoples. The ruling party perceived indigenous peoples as “not civilized peoples” and allowed the Non-indigenous people to take away their lands. It wasn’t until 1874 when the Mutan Village Incident broke out, that the Qing Government was surprised at the dispatched Japanese military and changed the passive attitude it had adopted in Taiwan. The policy of the Cultivation of Mountain and Barbarians(番) was announced. But, in the following year, the “Battle of Shitoushan” was initiated by the Qing government to attack the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj. That battle resulted in serious deaths and injuries. This battle exposed the truth behind the “Policy on the Cultivation of Mountains and Barbarians” as actually being “attack indigenous peoples with armed force.”

After the Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed in 1895, the Japanese began ruling Taiwan and the civilizing barbarian policy changed along with the times. Most policies involved social ‘comforting’, threatening by force, collective migration, and empirical education. At the beginning of their rule, the Japanese focused on quelling the resistance of the Non-indigenous people to them and adopted a ‘comfort policy’ for indigenous peoples by rewarding them with land and property and selecting leaders who were close to them.

In 1910, the “five-year barbarian civilizing program” was implemented to set up administrative agency for indigenous affairs, and conducted measurement for lands owned by indigenous peoples. Even the Japanese military was dispatched to both Northern and Southern Taiwan to suppress indigenous peoples. The “South Barbarian Incident” in 1914, for example, was caused partly by the attempts of the Japanese to confiscate guns owned by Paiwan people. The Paiwan people on the Hengchun Peninsula, thus, resisted. In the end, the Japanese mobilized about 2,000 soldiers as well as two destroyers to control the riot. The Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj was ended accordingly.

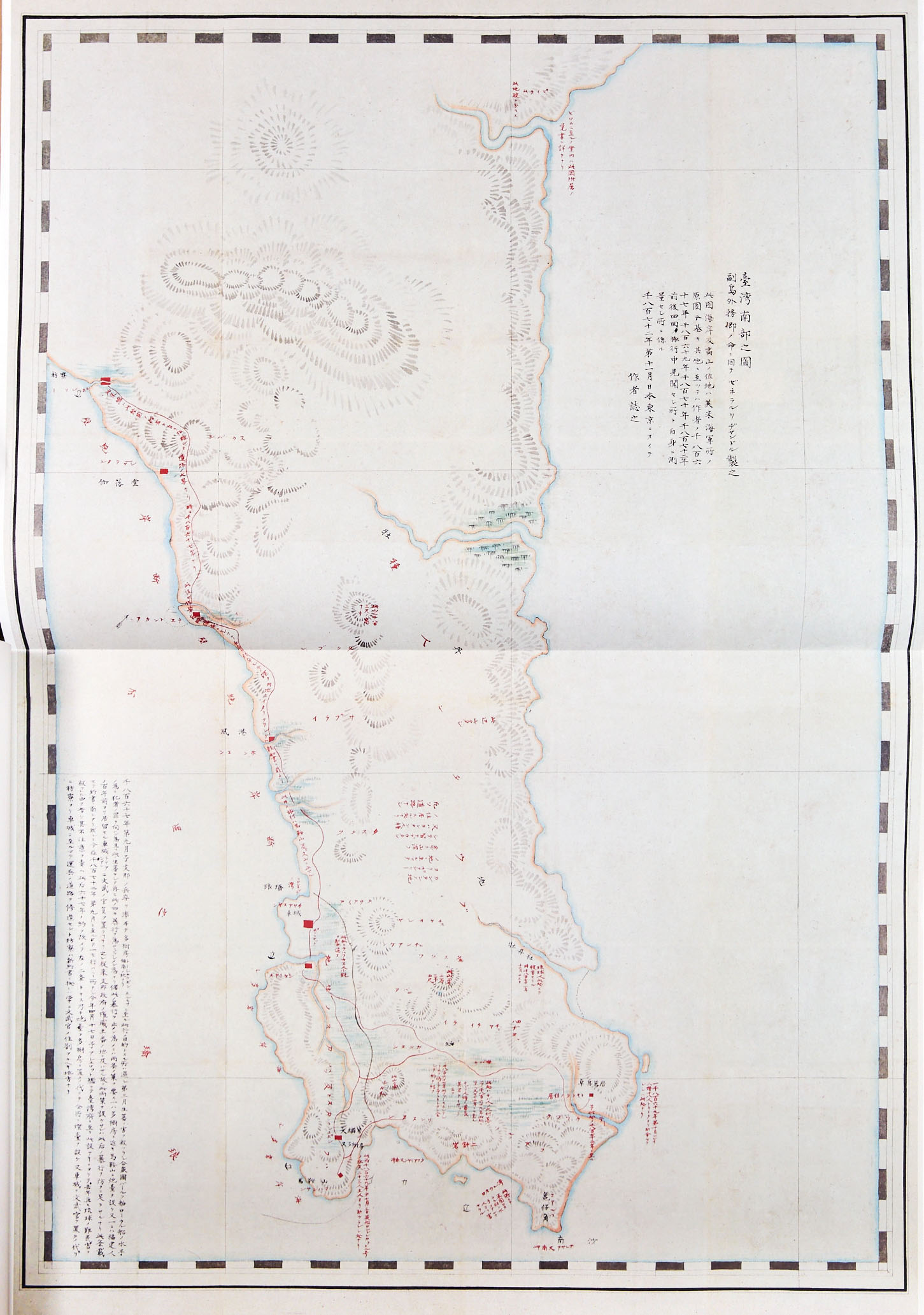

Map of Southern Taiwan, inside front《臺灣原住民族歷史地圖集》.

Civilization by Foreign Powers

and the Gradual Loss of Ethnic Culture

The Paiwan scholar, Yeh Sehrh Bao thought that the “South Barbarian Incident” demonstrated the attempts of the Japanese after their ineffective barbarian civilizing policy at the beginning of its ruling. Later, indigenous peoples lost the power to maintain their autonomy and were forced to be included in the state system. In 1931, the Office of Governor-General - due to the “Wushe Incident” in the previous year - issued the “Guidelines on Barbarian Civilizing Policy”, with collective migration as its priority policy. The act to move indigenous communities from North to South at a long distance was an attempt to disrupt the regional and social relations between indigenous communities. In 1940, Japan was fully engaged in the Pacific War and became more active in promoting empirical education. It even recruited indigenous peoples to organize “the Takasago Volunteer Army” for an expedition to Southeast Asia. Simply put, over the course of the 50-year Japanese rule, the Japanese included indigenous peoples in the colonial system more systematically. At this historical stage, the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj like most indigenous communities had its traditional social order suppressed by the ruling political power, and quickly collapsed.

After the war, Taiwan was ruled by a new government when the National Government relocated in Taiwan. Although Taiwan was ruled by a different power, the National Government inherited the policies of the Qing Dynasty and the Japanese to ‘civilize’ indigenous peoples with Non-indigenous education. Due to factors including local autonomy, national education, and political democratization, as well as a rising awareness pushed by the indigenous movement of the 1980s, the status, living standards, and self-identity of indigenous people was improved. But due to the long-term intervention of foreign powers, traditional social structure, and lifestyle, the economic activities of indigenous peoples became very different from the past and were further fragmented.

From a macro-perspective, during the development of the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj, contact with foreign civilizations caused a lot of battles and migrations, while foreign civilizations were presented as colonialists who promoted ‘civilizing barbarians’ which pushed history to a pessimistic conclusion in the final collapse of the Kingdom.

The Path to Search for the Ancestral Spirits

of the Descendants of the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj

In fact, studies on Taiwan’s indigenous history and culture all face a common challenge: lack of written historical literature from their own perspective. This is because indigenous peoples in the past had not developed written texts as a tool to keep records. Thus, because history has been dominated by written texts, indigenous history has long been simplified. Tracing heavily depends on foreign civilization or observations, studies, records, or interviews conducted by foreigners. Fortunately, in recent years, owing to the promotion of writing one’s own history from the perspective of the ethnic group, the construction of the subjectivity of indigenous history becomes possible and the history of the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj has gradually been revealed.

Joseph Change, a descendant of the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj during an interview burst into tears and said, “I felt the sorrow and sadness for my ancestors’ great achievements. I really love my family and research. As a researcher, I need to share the responsibilities of the Paiwan people, so I work very hard for the field studies and investigations of community heritage sites. I have not yet fulfilled my responsibilities because in the past the national system did not concern itself too much with indigenous peoples, and I have a responsibility to represent my ancestors’ history to the world.” Change spent a lot of time and effort to conduct oral interviews with the elderly in communities, and literature review, for he wanted to know his ancestors’ hardworking history. Now, he has published several research works for help others trace the historical clues of the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj.

In fact, contemporary scholars and descendants repeatedly emphasized the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj as being a relatively independent confederation. From the meaningful discourse of Mamazangiljang as the common identity of Paiwan, to the exploration of historical events and meanings less mentioned in mainstream Taiwanese narrative history, we can conclude that the Netherlands’ military attack on Tjaquvuquvulj indirectly gave Koxinga the opportunity to take over Taiwan, and that the Shitoushan Battle and the South Barbarian Incident revealed the unfair treatment of rulers towards indigenous peoples.

This hidden past behind the memories of mainstream narrative history presents a framework for ethnic groups to understand themselves, to construct national history, and shape collective identities. Through publications, the descendants interpret and represent the history with data, and proper assumptions are made to portray the characteristics of the Kingdom of Tjaquvuquvulj. In the present, this means that we are able to have a much clearer understanding of our ancestors’ achievements. We can see a long path to search for the ancestral spirits in front of us.

Please note that words of “barbarians” “uncivilized” used in this Issue only reflect to original texts used in the quoted historical literature and they do not contain any discrimination.

─ References ─

張金生,《排灣族Mamazangiljan制度及其部落變遷發展之研究》,臺北:國立政治大學民族學系博士論文,2013年。

童元昭、葉神保,〈Tjaquvuquvulj 的散與聚:跨部落集體性的多重再現〉,花蓮:《臺灣原住民族研究季刊》,第6卷第4期,頁39-75,2013年。

葉神保,《排灣族Caqovoqovo(內文)社群遷徙與族群關係的探討》,花蓮:國立東華大學族群關係研究所碩士論文,2002年。

葉神保,《日治時期排灣族「南蕃事件」之研究》,臺北:國立政治大學民族學研究所博士論文,2014年。

葉高華,〈從山地到山腳:排灣族與魯凱族的社會網絡與集體遷村〉。臺北:《臺灣史研究》,第24卷第1期,頁125-170,2017年。

歐陽泰(Tonio Andrade),鄭維中譯,《福爾摩沙如何變成臺灣府?》,臺北:遠流出版社,2017年。

蔡宜靜,〈荷據時期(1624∼ 1662)大龜文王國形成與發展之研究〉,花蓮:《臺灣原住民研究論叢》,第6期,頁157-192,2009年。

蔡宜靜,《荷據時期(1624∼1662)大龜文王國形成與發展之研究》,嘉義:南華大學建築與景觀學系環境藝術碩士論文,2009年。

譚昌國,《排灣族》,臺北:三民出版社,2007年。