Sedan chair riders, Paiwanized Pinuyumayan People, great witchcraft, the nobility system…according to historical literature, the “Seqalu People” long ago once ruled Southern Lonckjau area had many mysterious legends and records. Formation of ruling class and political power of that indigenous group gave the practical rights to rule, levy taxes, and determine life of indigenous peoples. In the end of Qing Dynasty, when faced invasions of super powers such as the US and Japan, this indigenous group used its diplomatic capability to defend integration and sovereignty of its homeland.

As shown in the records of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), since the Era of Discovery, in the southern tip of Taiwan, records of “Lonckjau” was found. In the 17th Century, the VOC stepped on the land of Lonckjau because of their search for gold mines in “Pinuyumayan” on the east side of Formosa and Lonckjau was on the way. According to the Netherlands records, in Lonckjau, there were about 16-18 communities led by one Lonckjau leader who had the right to determine people’s life and to appoint community leaders.

The Netherlands who arrived in Lonckjau made its leader surrender to the power of the Company and in 1642, they sent armed force to suppress Lonckjau. In 1645, both sides entered a treaty and since then, the power of Lonckjau leader was greatly reduced. His right to collect taxes from his community members was taken away by the Company. But the Lonckjau Confederation was not collapsed; even before and after the Mutan Incident, Tooke-tok, the leader of the 18 indigenous communities negotiated with the US, Japan, and the Qing Dynasty and played a key role in diplomacy.

Long before the arrival of the Netherlands and non-indigenous people in Pinuyumayan, Lonckjau people had been very familiar with the route on the Southeast Coast to Pinuyumayan. According to literature, Lonckjau people were originally Kazekalan people who migrated to the South from Jhihben and the Japanese named them the Seqalu People, later referred to as the Paiwanized Pinuyumayan People.

The 18 Communities of Lonckjau,

the Ruling Power in Southern Taiwan

In the Qing Dynasty, Paiwan community in the north of Fonggang River was called the Up 18 Communities of Lonckjau and later, Japanese called them Neiwn Group of Paiwan People, Tjaquvuquvulj; the area between the South of Fonggang River and Eluanbi on Hengchun Peninsula was referred to as the Down 18 Communities of Lonckjau, Hengchun Group of Paiwan People, mainly the Seqalu People. In general, the 18 Communities of Lonckjau cover the area of four leader families of the Seqalu People on Hengchun Peninsula as well as Paiwan and Amis communities. The name of Seqaluwas not well-known to all because since the ruling of Qing Government in Taiwan, the ruler regarded the Lonckjau area as a uncivilized one and the public and the private mostly called communities and inhabitants in Hengchun area as “the 18 Indigenous Communities of Lonckjau.”

After the ruling of Japanese in Taiwan, a series of systematic investigation and classification were conducted. From Torii to Utzukawa, through oral history of communities and family records, the origin, migration, allocation, and relationship of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples were classified including the relationship between the 18 Communities of Lonckjau and the Seqalu People. The name of the “Seqalu People” became independent from the 18 Communities of Lonckjau.

The Legend Sedan Chair Rider

the Seqalu People

Legend has it several hundred years ago, a group of Pinuyumayan people came from Jhihben Community on the East Coast migrated southbound along the coastal line and then settled down in Hengchun. They married Paiwan people and were Paiwanized. This group built four communities: Cilasoaq, Soavari, Longduan, and Savaruk, generally referred to as the “Sukalo, Su-qaro, Seqaluor Suqaroqaro” People.

According to the legend, the Seqalu People conquered South Paiwan Community during their migration because of its powerful force and great witchcraft. For a long period of time, Paiwan people were scared of witchcraft of Pinuyumayan people and it was said that after the Pinuyumayan people begin to pray, local harvest can be expected and more games will be hunted. On the contrary, once a spell is casted, people will become ill and insects will eat crops and crops will die. Paiwan People believed in the existence of witchcraft of Pinuyumayan people and were scared and dared not to get closer the Seqalu People. Thus, the legend about south migration of Jhihben Community collected from the “Report of Barbarian Habit Survey” in Japanese era or “Taiwan’s Takasazoku Studies,” the south migration of the Seqalu People and their negotiation with the Paiwan people were stories related to witchcraft.

In the legend, when these members of Jhihben Community of Pinuyumayan came to Da Niao Community, local Paiwan people gave them difficulty and they were forced to stay on reefs. The members of Jhihben casted a spell to call for wind and rain and recede the sea. The land was flooded and Paiwan people had to run for their safety. When they arrived in Hengchun area and through divination, they were told here is a land in blessing and decided to settle down.

The Paiwan people knew these outsiders from Jhihben possessed witchcraft and created all sorts of obstacles for them. First, they released some mountain pigs to attack those from Jhihben and Jhihben members used fire to fight against mountain pigs. Then fierce dogs were out and Jhihben members cut some hair to mix with sticky rice cake and fed these dogs. Dogs could not make any moves. The Paiwan people, thus, were scared but they decided not to surrender. Jhihben members cast a spell for a fire and two years in a row, there were droughts. In the end, the Paiwan people had to make peace with Jhihben members.

Jhihben members negotiated for the terms that, “In the future, one tenth of what harvest in your field shall give to us and thighs, brains, livers, hearts, and ribs of animals you hunt shall also offer us as articles of tribute. We shall have the priority right for mountain products; we shall be invited to any community meetings for hearing and arbitration.” The Paiwan people accepted the said terms and Jhihben members began to interact with the Paiwan people. Once there was a community meeting, Jhihben members would ride a sedan chair to attend and thus, the Paiwan people called them “the Seqalu People,” meaning the sedan chair riders.

Confrontation and Negotiation

of the Rover Incident and Mutan Incident

After the Seqaku people migrated to the Lonckjau area. The Amis people that long had been suppressed by the Pinuyumayan people also moved to the river mouth and the coast area of Lonckjau; Makatao people on the west coast because of invasion and suppression of Non-indigenous people who settled there and in the era of Emperor Daoguang in the Qing Dynasty collectively migrated to the south. Later, a group of Hakka Non-indigenous people also arrived. Each ethnic group leased land from the Seqalu People and paid their tributes to leader families of the Seqaluevery five years and did some labor works.

The Seqaluleader who took the lead to move to the south had three sons and one daughter; his eldest daughter and eldest son left in Savaruk and Ciljasuak to lead their communities respectively. His other two sons were also leaders of Tjuavalji and Longduan. For a long time, communities had their ups and downs, but these four communities were led by the four-leader system.

This group of “Paiwanized Pinuyumayan people"had been assisted by their armed force and witchcraft and finally obtained its leadership for 16 communities in the Netherlands era and 18 in the beginning of Qing Dynasty, so called “the 18 Communities of Lonckjau.” Later, 18 was reduced to 14 and they were referred to as “the 14 Indigenous Communities of Lonckjau.” No matter how these communities are named, there were more than one leader including the Chief, the Second Chief, the Third Chief, and the Fourth Chief.

The Big Chiefs belonged to the Ljagaruljigulj family from Ciljasuak and governed the highest number of communities such as Chiazhilai, Mutan, Chong, Nunai, Gaoshifuo, Wenshuaishan, Wuziyong communities of Paiwan, Gangko community of Amis, and Baoli, Shanglin, Tongpu, Wenshuai, Checheng, Juiaopeng, Sichungxi, Gangzai, Biaogugong of Non-indigenous communities.

The Second Chiefs belonged to Mavaliw Family from Tjuavalji and governed the second highest number of communities including Bashimuo, Jiaxinlu, Mutanlu, Caopuhou and part of Sigelin, Bayao, and Kuazi communities of Paiwan; Luofuo community of Amis, and few Non-indigenous people’s settlement.

The Third Chiefs were from Ljacjligul Family of Savaruk and governed Bayao, Sigeling and Zhu of Paiwan and did not govern any community of Amis.

The Fourth Chiefs were from Ruvaniyaw Family of Longduan with the most limited power and governed only their own communities, Houdongshan of Makatao people and Dashufang, Dabanfu, and Caotang of Non-indigenous communities.

In the second half of the 19th Century, leadership of Ciljasuak came to the peak and was officially referred to as “the 18 Communities of Lonckjau” by the Qing government and the Japanese and in various diplomatic events, it demonstrated its good diplomatic relationship. In 1867, the US merchant ship, the Rover, was wracked off the coast of Painwan; the indigenous people, thus, went kanasan (head hunting) to kill the American sailors. It was the so-called the “Rover Incident.” This international event almost triggered the Sino-Us military conflict. Le Gendre, the Ambassador of the United States to Xiamen, China at that time met with the brother of the First Chief of Ciljasuak, Tokitok and his adopted son, Jagarushi Guri Bunkiet, later also joined the negotiation. Jagarushi Guri Bunkiet, was appointed as the First Chief of Lonckjau after the negotiation by the Qing Government.

In the Mudan Incident in 1874, Lonckjau also played a role in the military and diplomatic negotiation between the Qing Government and the Japanese. The First Chief, Jagarushi Guri Bunkiet, led his community leaders to surrender to the Japanese. The Japanese Commander, Tsugumichi Saigo, gave him western guns, swords, and letter of acknowledgement. After 1895, Taiwan was ruled by the Japanese and Jagarushi Guri Bunkiet, was busy in persuading community leaders in Lonckjau to surrender to the Japanese to avoid harms and losses.

The Japanese Office of Governor-General in Taiwan conducted land inventory check and regulated “the Joint Ownership Shared by Civilized and Indigenous People” that denied land ownership of community leaders and the noble of Seqalu People as well as their privilege to receive tributes. The residential areas of the four communities were included in “general administrative areas.” Some Amis returned to their home in Taitung and those staying in Hengchun settled down with Makatao and Non-indigenous people. They gradually owned private lands and even moved to Tjuavalji to simulate and married with other ethnic groups. The Master-Servant Relationship between the Seqalu People and people they ruled after the intervention of state power became loosen.

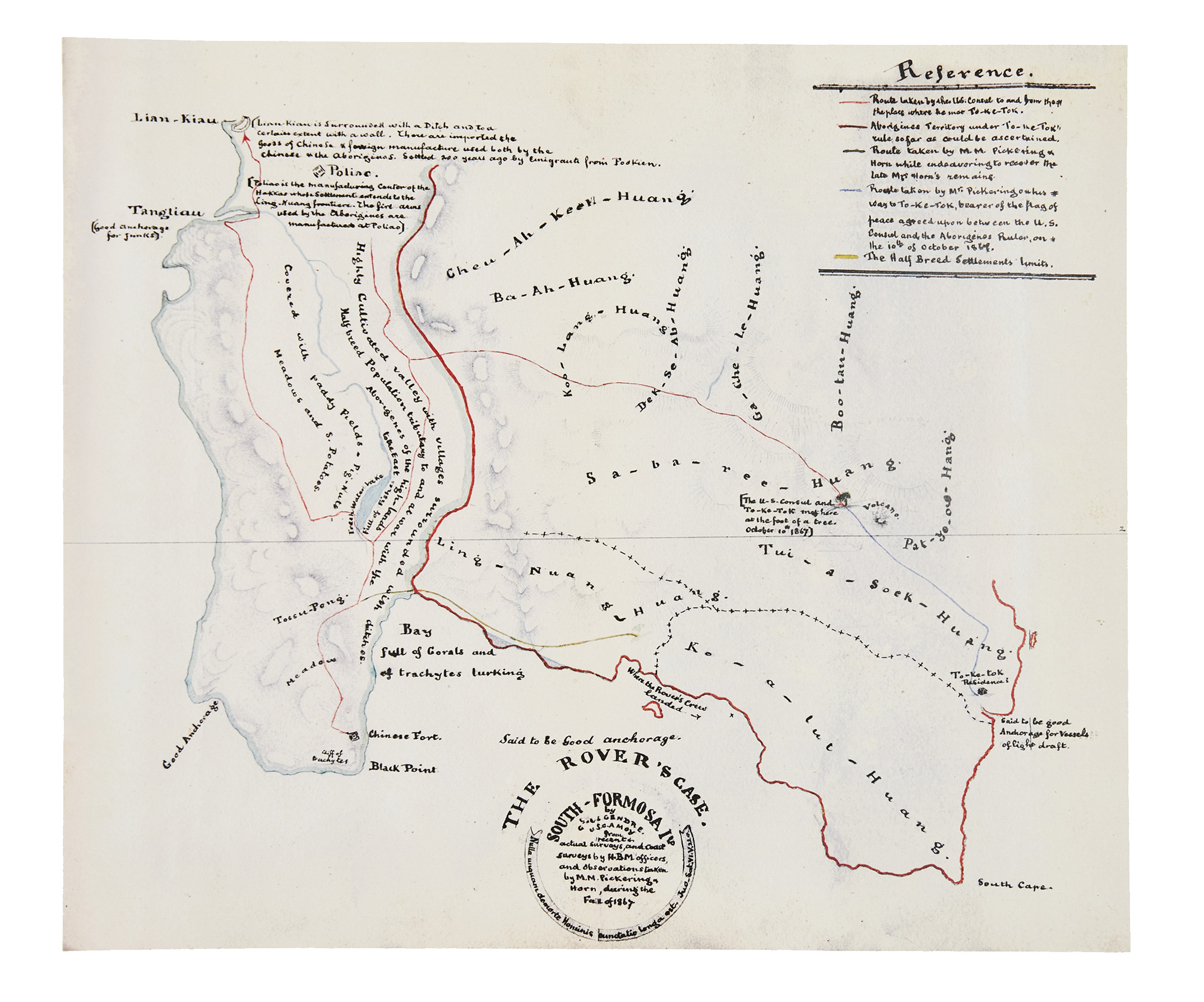

The Rover Incident-Map of South Formosa ,inside front《臺灣原住民族歷史地圖集》.

Community

Imaged by Others

In general. “the Seqalu People” was referred to those inhabiting in the South of Hengchun and categorized as living in Paiwan Community before and after Japanese ruling, but they used this name to distinguish themselves led by the four leaders’ families from other communities. They used this name because they till now are not recognized by the government ethnically and they became “an ethnic group without a name.”

According to their own mythologies, family records, and legends, they were directly described as the Pinuyumayan people from Jhihben and migrated to Hengchun due to some reasons. With mighty witchcraft and armed force, they conquered other indigenous people and became the most powerful leading political power. But because their languages and folk customs were identical to those of Paiwan People and even similar with those of Non-indigenous People. Customs could only be preserved in the mind of community leaders and the elderly. Thus, the name of “the Seqalu People” was never found in the ethnography kept by the westerners such as Le Gendre or the first group of Japanese ethnographic scholars including Ino Kanori, Torii Ryuzo, and Awano Tutonosuke.

These explorers and scholars did not keep the record of the name, but certainly it did not deny the existence of the name or ethnic group. Probably, it was ignored at that time or was buried in the deep side of history or at the corner of the field.

For the first time, in the “Barbarian Habit Investigation Report” published between 1920 and 1922, the term of “the Seqalu People” appeared in the historical literature. Japanese Koshima Yoshimichi proposed the classification concept of “Seqalu” but because culturally, it was difficult to distinguish them from Paiwan People. In 1935, “Studies on Taiwan’s Takasamazoku” put the “Seqalu” as one branch group of Paiwan People and in other chapters about the Pinuyumayan people, Seqaluwas referred to as the “Paiwanized Pinuyumayan people.” In 1936, Abe Akiyoshi in his paper, “Where Does the Puyuma Go? Presence of Mysterious Seqalu” recorded Seqalulegends from various sources and portrayed its historical manners.

These investigation records, however, were completed from the perspectives of the third party. It is still our task in the contemporary time to think how to develop and restore ethnical cultures. The paper, “Legacy of the Seqalu People” written by two experts of Austronesian cultural studies, Yang Nan-Chun and Hsu Ru-Lin, describes the pity and sadness to save the sunset of ethnical culture and the history that now cannot be restored for many descendants now did not know the name of their ancestors, “the Seqalu People.”

Where Does the Puyuma Go?

People without a Name

Puyuma symbolizes the Pinuyumayan people and the paper of Abe Akiyoshi, “Where Does the Puyuma Go?"published in 1936 was borrowed to describe the nostalgia and helplessness of the ethnic group. When describing the Seqalu People, Abe used touching and sorrowful styles to tell the ups and downs of the ethnic group by mixing together legends and historical materials.

Indeed, who are the Seqalu People? How shall we understand and respond to this term that appeared in the historical literature and exactly existed? Both the 18 Communities of Lonckjau and the Seqalu People tie closely to the important historical moments of Taiwan, such as, the Rover Incident, the Mudan Incident or the comforting and governing policies of the Qing Government and the Japanese towards the indigenous peoples. But “Seqalu: has been hidden in the deep side of history and it relies us to further study and match historical imagination in the contemporary time.

In recent years, due to the popularity of adaption from novels to films and TV programs, there has been a rush in the search of “Seqalu.” The existence of the Seqalu People is an issue that needs to be proved with historical literature, archaeological studies, oral interpretation, and academic research, but about cultural restoration of “the Seqalu People,” is their cultural personality matching with contemporary imagination of the ethnic group? What are the commonly identified core values? Shall be define a family system with only the connection of blood relationship, geography, and language? In fact, the path to trace back the origin is difficult and rebuilding ethnic history often receives harsh criticism and doubts reflecting the situation of the contemporary thinking.

From the past to the present, we can only image that in the rich and diverse history of Taiwan, there were a group of Pinuyumayan People in Southern Taiwan building loose political power with armed force and witchcraft similar with that of a confederation. Facing the invasion of foreign powers, its leader tried his best to negotiate. In a certain type of format, these efforts protected the land from wars.

Please note that words of “barbarians” “uncivilized” used in this Issue only reflect to original texts used in the quoted historical literature and they do not contain any discrimination.

─ References ─

臺灣總督府臨時臺灣舊慣習調查會原著;中研院民族學研究所編譯,《番族慣習調查報告書•第五卷,排灣族•第一冊》。臺北:中研院民族所,2003。

楊南郡、徐如林。與子偕行。臺北:晨星,2016

劉還月,《琅嶠十八社與斯卡羅族》。屏東:墾丁國家公園管理處,2015

移川子之藏等原著;楊南郡譯著。台灣百年曙光 : 學術開創時代調查實錄。臺北:南天,2005。

牡丹社事件始末。豪士(Edward H. House)原著;陳政三譯註征臺紀事。臺北:五南,2015。