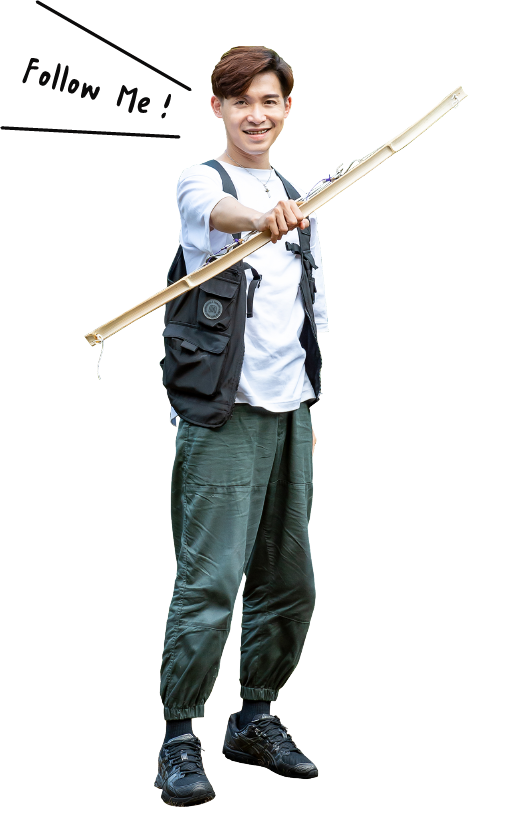

Edward (aka Misanthropic Philosopher on social media)

Hosts a Facebook fan page with 220,000 followers

A Chinese Teacher in senior high school

An expert on the Taoist philosophies of Laozi and Zhuangzi

180 cm tall and speaks flawless Mandarin

I am ashamed to admit that my knowledge about Taiwan’s indigenous peoples is quite limited and superficial. I teach Chinese literature in senior high school, and the relevant materials included in the curriculum mainly touch on the history of indigenous communities. There is a lesson that selects two modern poems from the Atayal poet Walis Nokan’s essay entitled “Wushe (1892-1931)”, focusing on the fate of the Atayal survivors in the “aftermath” of the Wushe Incident, the last major indigenous uprising against colonial Japanese forces that took place in 1930. Such a perspective is quite special because most history textbooks tend to focus on the “causes and results” of the incident, but rarely address what has become of the survivors and their situations afterward.

While preparing for the lecture, I learn that the Wushe Incident actually involved two episodes. The Atayal uprising was followed by a Japanese-led counterattack in retaliation, in which the Toda-Atayal Community was incited to kill the remaining 561 Seediq survivors in the shelters. Only 298 people were left alive after the attack, most of whom were the elderly, women, and children. Almost desperate, they attempted several times to hang themselves to death but at last decided to save their lives to continue the clan bloodline. Having learned about this tragic episode in Taiwanese indigenous peoples’ history, I cannot help but feel a sense of respect and admiration for their ethnic consciousness and vitality, which are so strong and resilient that they form a vital part in shaping the so-called “spirit of Taiwan.”

The indigenous communities have long been the most disadvantaged class in our society. Many of these people are stuck at the bottom of the social ladder doing hard physical labor work. In the past, young teenage girls were even forced to work as child prostitutes to support their families. Since I have never been troubled by such problems in the process of growing up, now I am often “terrified” by these stories and cannot bear to read on. This makes me realize how much they have suffered from the oppression and exploitation of the Non-indigenous peoples over the past decades, which causes me to feel “guilty” from time to time.

Unlike most of the historical materials which tend to be tragically oriented, my experiences of interacting with indigenous people in real life are mostly relaxed and enjoyable. Since none of my friends is indigenous, my limited experiences with them are all gained from traveling. In my first year of work, I attended the faculty trip to the Bulaubulau Community in Yilan County. That was my first time to the indigenous community, where I was given a tour of the village’s environment, participated in such hands-on activities as traditional weaving and millet wine brewing, as well as enjoyed an authentic Atayal meal. When we were about to leave, the local guide mentioned that the village was in dire need of teachers and that we would be more than welcome if we were willing to come back to teach. Though that might have sounded like a casual remark, I do believe the lack of educational resources is a real problem for indigenous communities.

Afterward, the school arranged a graduation trip that included a visit to another indigenous community. But with a large group of students, we could only take a cursory glance at the place and were left unimpressed, which was really a shame. I’ d like to suggest that schools incorporate more hands-on activities into the curriculum of future field trips to indigenous communities to make them more educative. Otherwise, hasty visits as such would only serve as a means to satisfy the Non-indigenous people’s imagination of indigenousness.

I am very aware that my knowledge about indigenous people is limited to the level of sightseeing, which is merely an act of “consumption” that aims for a feeling of freshness and novelty. And the villagers would surely try their best to please Non-indigenous tourists with experience activities to “meet their anticipation of indigenous life.” That’s why I said yes without hesitation upon receiving the invitation from Indigenous Sight. I never expected to have such a good chance to stay in a genuine indigenous village and learn about their way  of life. I hope this first-hand experience will serve as a resourceful reference for my lectures and that more people will get a better understanding of indigenous culture through the platform of Indigenous Sight.

of life. I hope this first-hand experience will serve as a resourceful reference for my lectures and that more people will get a better understanding of indigenous culture through the platform of Indigenous Sight.