Legend has it that the people of Atayal originated in the region of the current Township of Ren’ai, Nantou County. The first ancestors appeared when a huge stone cracked apart, and villages were established afterward. As the land became insufficient to accommodate the increasing number of clansmen, their ancestors decided to leave their homeland in search of new land for future generations. There were three brothers among them who came to Quri Sqabu, and from there they embarked on three different routes of migration: Kbuta, the eldest brother, headed westward over Papak Waqa (the Mt. Dabajian), while Kyaboh, the second eldest, climbed over Rgyax Towpoq (the Mt. Nanhu) and settled in the Basin of the Heping River. Kmomaw, the youngest, moved along Llyung Mnibu (the Lanyang River) and ended up in Minnao, the current Datong Township, Yilan County. These three major areas of settlements mark today’s geographic distribution of Taiwan’s Atayal people.

The Atayal can be divided into different subgroups and dialect systems, such as Squliq and Ci’uli. The stories about their origin may vary according to different lineage groups. The legend of the three brothers, for example, is a common view shared by the Squliq, while those of the Ci?uli are more diversified, which, as Wilang speculates, could be due to its early subgrouping.

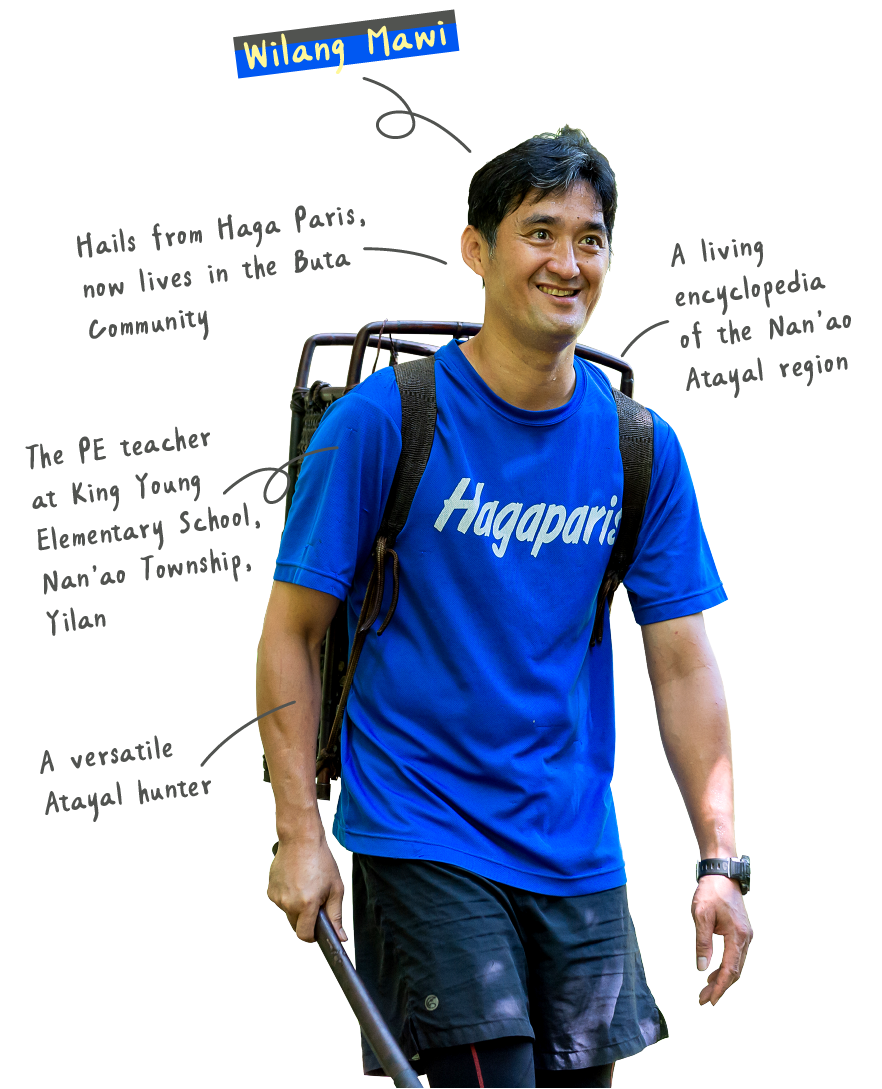

After Kyaboh settled in Eastern Taiwan, the growing population of the community prompted its clansmen to migrate again in search of a suitable place to live. Take Wilang’s ancestors for example. They relocated to the Nan’ao area and set roots in Haga Paris. “In the Atayal language, ‘Haga’ means piles of rocks, and ‘Paris’ means enemy. When our ancestors first came here, they spotted piles of rocks and people they did not know, whom they considered enemies. That is how the place derived its name,” explains Wilang.

Long before the Atayal relocated to Nan’ao, the area had been home to another group of indigenous people called “Qolin” in Atayal, meaning “short and small guys.” Wilang said that originally the community elders thought the Qauqaut were Non-indigenous, but it was not until they searched through countless written documents that they realized that in the very beginning, the Qauqaut had settled in the area of Truku even earlier than the Taroko people, who later drove them to Nan’ao, from which they were expelled again by the Atayal to the region of today’s Su’ao Township. That is why there are still such place names as “Qauqaut Cape” and “Qauqaut-keng River” in the Su’ao area.

Later during the Japanese colonial period, many Atayal communities were forced to move from deep within the mountains to foothills and lowlands under the Collective Relocation Policy. After Taiwan was returned to the Republic of China, the spirit of the policy was continued by the Nationalist government through the implementation of the Mountain Administration Reform Project. It was not until around 1966 that the relocation of the Atayal clans in Nan’ao was completed, with Wilang’s family being the last to leave. His elders, however, still maintain a deep connection with the mountain forests where they have lived so long. Therefore, Wilang has been following them to visit the mountains as a child and accumulated a wealth of knowledge about the natural environment. “I bet you can never find a second person in Nan’ao who is about my age and loves to spend time in the mountains,” says he playfully with a hint of regret. “The older generation in my family is well-versed in how to survive in the wild but knows nothing about farming. What can they do in the lowlands? So, they have no choice but to move toward the mountains. I’m glad that we are the last family to move down, which enables me to acquire wisdom derived from the daily experience of the older generation that my peers can never have access to.”

Later during the Japanese colonial period, many Atayal communities were forced to move from deep within the mountains to foothills and lowlands under the Collective Relocation Policy. After Taiwan was returned to the Republic of China, the spirit of the policy was continued by the Nationalist government through the implementation of the Mountain Administration Reform Project. It was not until around 1966 that the relocation of the Atayal clans in Nan’ao was completed, with Wilang’s family being the last to leave. His elders, however, still maintain a deep connection with the mountain forests where they have lived so long. Therefore, Wilang has been following them to visit the mountains as a child and accumulated a wealth of knowledge about the natural environment. “I bet you can never find a second person in Nan’ao who is about my age and loves to spend time in the mountains,” says he playfully with a hint of regret. “The older generation in my family is well-versed in how to survive in the wild but knows nothing about farming. What can they do in the lowlands? So, they have no choice but to move toward the mountains. I’m glad that we are the last family to move down, which enables me to acquire wisdom derived from the daily experience of the older generation that my peers can never have access to.”

During the era of Japanese rule, different indigenous communities were resettled in the same area in the lowland, where the territorial boundaries were blurred. Such an arrangement ignored the indigenous peoples’ emphasis on the clearly defined boundaries between neighboring villages. This, along with the varying degrees of sinification that cause differences in lifestyles and concepts, gives rise to many conflicts among various communities. Although now a resident of the Buta Village, Wilang knows clearly that Haga Paris is the only place where he belongs.

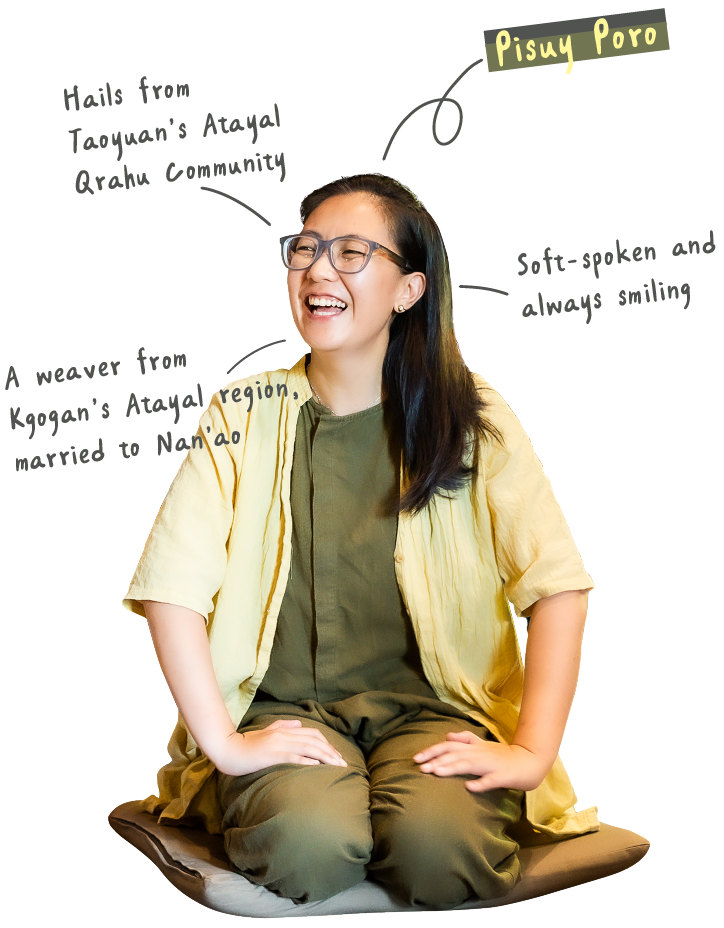

Having set his roots in the mountains and forests, Wilang is deeply in love and identifies with his indigenous culture. He and his wife, Pisuy, work step by step toward rediscovering and solidifying their sense of self-identity through the revitalization of the Atayal culture. They hope to call on more partners to join them to break out of the mist of cultural dislocation and find their way home.