Being referred to as the Kingdom of Middag by Netherlanders, the Tatuturo (known as Dadu today) Confederation used to be an invincible supra-community alliance in Central Taiwan. The community leaders called upon their people to resist the foreign forces from the Netherlands, Koxinga, and Cing Dynasty with force. Though they were defeated in the end, the legend of the Tatuturo Confederation still lives in the heart and memory of modern Taiwanese as if they were saying, “We have never been away,” waiting to be recalled from history.

He drew the bow back with his strong arms, squinting his black eyes to focus while holding his breath.

Every year before the sowing season, this was the time when he demonstrated his power over the centre of Taiwan as well as his commitment to his peoples. Was it a mighty power or witchcraft? The arrow ripped through the air of Dadu Plateau with a furious whizz. Everyone stared at the same direction. Anywhere the arrow travelled would be fertile with plentiful supplies of food all year round, having a good harvest without being trampled over by pigs or deer. On the contrary, places where the arrow did not whizz past would face withered crops and become barren for the following year.

People from each community would bow to him, hoping for peaceful days. Anyone hunted for deer in the fields would share meat with him in gratitude for his leadership and protection. He is always remembered as the King of Middag, be alive or dead.

Hegemony over Central Taiwan

Powerful and Mighty King of Middag

The legends of the King of Middag (as keizer van Middag in Netherlands) and his confederation (communities of Tatuturo were the core leaders and often referred to as the King or Kingdom of Tatuturo, but the political system was in fact confederation or inter-community alliance) were considered by many anecdotes in the plains region of the centre of Taiwan. This, however, is not surprising as many people today still think that Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples have already become completely Sinicised.

The King of Middag and his confederation, in effect, had only been active for a century according to the limited records in literature. However, they were one of the few inter-community powers in Taiwan’s history that could be compared to the Chinese pirates, the Netherlands army, Ming Jheng forces, and the army of Cing government. The communities that comprised the Confederation are Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples that we know of today. They had been through the collapse of the Confederation, faced unrest at home and from outside powers due to the “Fighting Barbarians (番) with Barbarians” policy devised by colonial governments, to migration to Houshan and Puli. Even today, they are still fighting hard for their “existence.”

We are unable to know as to how the Tatuturo Confederation came about. Yet, we only know the earliest record of the Confederation was in 1638 when the Chinese ships were stranded on the coast of their territory, and people and goods on the ships never returned to China.

The power of the Confederation covered 19 or 20 communities and even up to 27 in its heyday. These communities, in accordance with the most recognised typology of indigenous peoples, include at least four Taiwanese indigenous peoples that were Papora, which the King of Middag belonged to, Babuza, Pazeh, and Aboan Balis, which had been referred to as Hoanya at first. In its heyday, another 7 communities included all the people of Taokas.

The Confederation’s territory ran from the south of Dajia River to Lugang to the north. This piece of land was described by foreign missionaries as “the most affluent place in Taiwan” with fertile soils and rich supplies of game. It was said that all kinds of grains, fruits, and vegetables could be found here. In addition to rich natural resources, the Confederation boasted its civilisation and advantageous geographical location. The plains on the west part of Dadu Plateau, unlike the neighbouring alluvial fans, were not affected by flood or the change of river course. What is more, spring water abounded near the plateau’s fault line, which gives this area a comparative advantage in terms of material resources. As a result, evidence of early forms of agriculture had been found in Papora related Luliao site of late Fanzaiyuan culture, which belonged to the Metal Age (or known as the Iron Age), in the prehistory of Taiwan. Tatuturo Confederation also dominated the river system of Dajia River and the lower reaches of Dadu River. While in the 17th century East Asia was experiencing a burgeoning maritime trade, smuggling also became rampant. This pivotal location of Tatuturo Confederation played an important role in its rise and coming to prominence. Perhaps in the 17th century, the estuaries of the central Taiwan witnessed the hustle and bustle of another form of “internationalisation.”

However, who exactly was the King of Middag? From limited literature, we are only aware that the King of Middag who had fought against the Netherlands army for times was Camachat Aslamies. After the war with the Netherlands army, he signed a treaty with the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) in 1645 and died two to three years later. His little nephew Camachat Maloe succeeded him, but Maloe was only two or three years old then, and therefore, it was Maloe’s stepfather, Tarraboe, that negotiated with the VOC and attended local meetings on Maloe’s behalf. Nevertheless, the Papora communities of Tatuturo were actually matriarchies, so the real power fell into the hands of Maloe’s maternal grandmother, i.e. Aslamies’ mother.

For now, we are unable to know how the Confederation worked, and what their matrilineal system implied. Why did they make the little successor come to the throne when the situation then was crisis-ridden? What was the reciprocal relationship between Tatuturo communities, which the King of Middag belonged to, and other communities in the Confederation? All we know is that the order made by the King of Middag were authoritative. He could mediate disputes, protect his subjects, and always had attendants accompanying him whenever he went out. Even after entering into the treaty with the East India Company, he could still prohibit Non-indigenous people and Netherlanders from dwelling in his dominions and learning the languages of “the King and his people.” Non-indigenous people and Netherlanders were only allowed to travel through his dominions.

The last battle:

reminiscing how valiant our ancestors had been!

Ja zijs-ja magdiwang baas (We celebrate the New Year).

Bao o mauloom zimiro mazikap i s-aam (Everyone gathered together to pay tribute to our ancestors with newly brewed wine).

Soall-en i s-aam magiting (Together we reminisce how brave our ancestors were.)

Airab mwuriiy i s-aam magiting (We, the old and young, aspire to be as valiant as our ancestors.)

– Tatuturo Communitiess’ Ritual Songs for Ancestors, Records from the Mission to Taiwan and Its Straits, Taiwan Literature Series, Vol. 4.

This song for ceremonies in honour of ancestors, which has been translated phonetically from Papora language into Chinese, was recorded by Huang Shu-jing from Cing government (approximately 1720) when the King of Middag and his confederation was about to collapse. As time passed by, however, we can no longer grasp its grammatical rules.

Since 1644, there had been a wave of competition of sea exploration internationally. The King of Middag on the island of Formosa who was once able to exert a powerful influence over the region had no choice but to be swept over by this trend. Yet, we cannot assume that before the arrival of foreigners, the Confederation had always enjoyed peaceful and tranquil days, and then started to spiral downward starting from the 17th century. What comes around, goes around. Perhaps the power of all the “kings” on this island ebbed and rose making them play different roles.

All in all, since 1644, the Netherlanders had started to subdue this force, which hindered their way to south or north on land. However, the first encounter was a failed attempt. Tatuturo communities set forests on fire prohibiting the Netherlands army from moving forward. Although the Netherlands army burned down Boder and Passoua communities, they had to stop battling as a consequence of bad weather and diseased soldiers. The next year they resumed the war, and this time they burned down 13 communities, killed 126 people, and captured 16 children, forcing the Tatuturo Confederation to agree to sign a treaty with East India Company. Since then, the King of Middag would have travelled south to partake in the “southern country assembly (landdag in Netherlands) annually and enter into negotiations about trade and land policies with leaders of other communities.

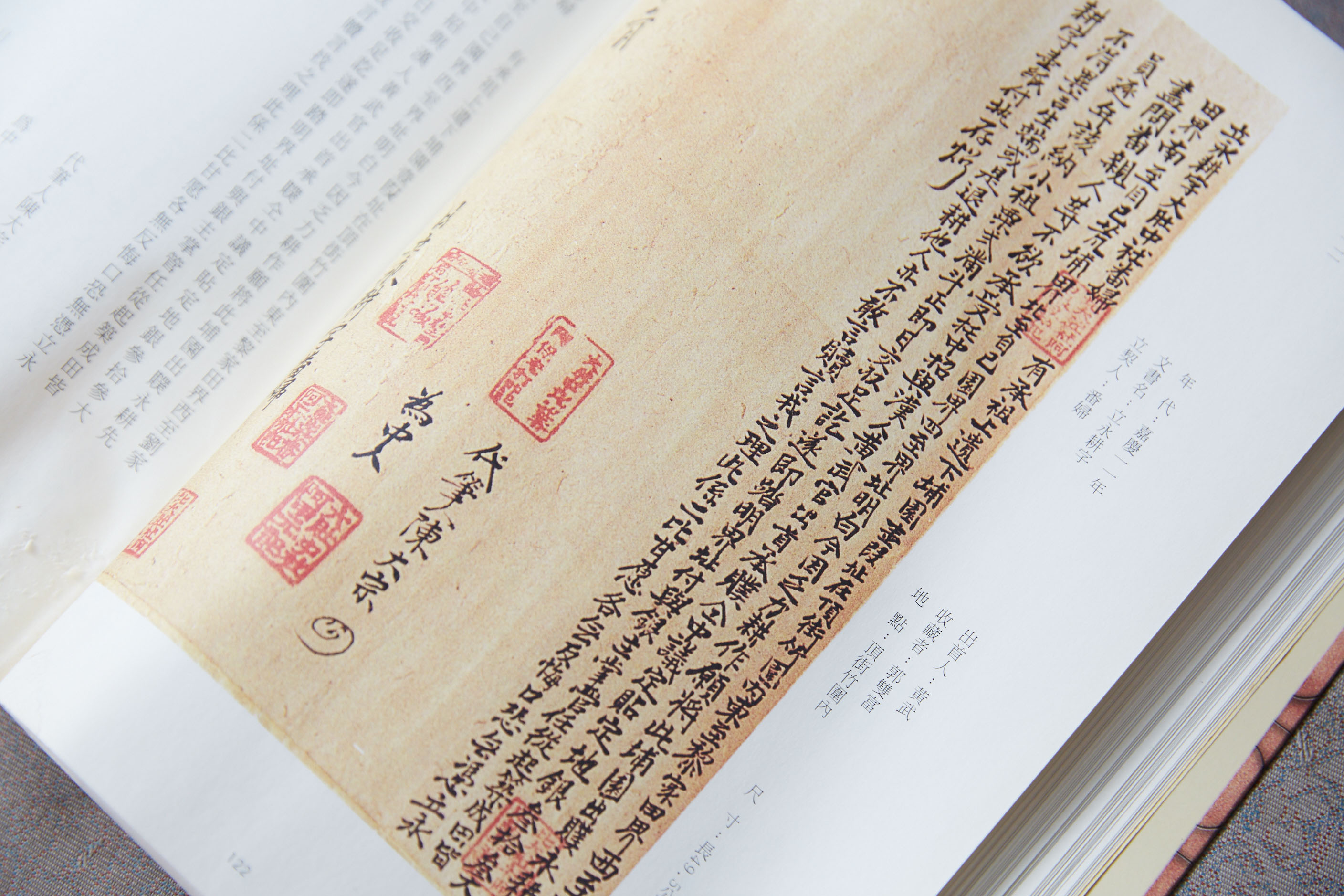

Inside front cover of the file of the VOC provided by Wong, Jia-Yin.

Nonetheless, we still do not have a clue what Tatuturo Confederation turned out to be after being subjugated to the Netherlands East India Company. It was highly likely to be semi-independent. Even though Non-indigenous people could come and go within the Confederation’s dominions to collect the revenue from deer hunting, but the revenue collected from this “most affluent place” was so much lower than other areas. What is more, though the clergy of the East India Company already started to mediate disputes in this area, Christians were still not allowed to dwell here, which shows that Tatuturo Confederation retained sovereignty to a certain extent.

At least we know that 16 years after the surrender to the East India Company before the Netherlands ruling came to an end and in the summer prior to the occupation of Koxinga in 1661, when Koxinga’s army invaded the dominions of Tatuturo’s Confederation because of the need for military provisions, the Confederation could still resist the invasion violently. Jheng’s (Koxinga’s) army fell into the Confederation’s ambush and died a tragic death under their spears. Jheng might have lost 2,000 soldiers. This was a tremendously fierce battle.

We could imagine that the recalcitrant resistance against foreign aggression, which could be compared to the anti-Japanese Wushe Incident initiated by Sediq, demonstrated the determination the communities had to sacrifice their lives for their homeland and people. Was the King of Middag then Maloe? If yes, he should have been 15 or 16 years, a very vigorous young man. As if trying to survive despair, how did the King of Middag and his warriors devise tactics and break the deadlock?

According to the literature of Cing Dynasty, Jheng’s army suffered some losses, but it managed to put down those Tatuturo indigenous warriors in the same year. The fact is after 70 years before 1730, the Confederation’s residents continued to resist foreign attacks, one wave after another.

Ancient Documents of Tatuturo Communities Inside front cover, compiled by Liou, Ze-min, published by Taiwan Historica of Academia Historica.

Gone with the Netherlanders, there came Ming Jheng forces. After Ming Jheng, it was Cing government that took over. Due to the passive ruling by the Cing government at first as well as the migration of Non-indigenous people toward central and northern Taiwan and their settling in there, the descendants of Tatuturo’s Confederation might have had some timeout to regain strength during the transition from Ming Jheng rule to the governing of Cing government. Unfortunately, the Confederation was undergoing power restructuring at this time. In particular, the rise of Pazeh community of Lahodoboo (Anli in Chinese language), a member of the Confederation, and its established tie with the Cing government as well as the diminishing power of Tatuturo communities resulted in the outbreak of the Taokas West Community Incident.

In the winter of 1731, as Cing government assigned much physical work, the West community of Taokas decided to stage a revolt. They burned down “yamen (the office of a public official in feudal China)” and even kept Taiwan’s division commander (the highest ranking military officer) in captivity. In August of 1732, to take credit for suppressing the uprising, Cing officials who had quelled the disturbances decapitated 5 naturalised indigenous people, who were members of the major Tatuturo communities, falsely claiming them as the “savages” who went on the rampage.

Taokas West Community Incident served as a trigger. The envelopments by Non-indigenous people and Lahodoboo community and their encroachment on the land were the straw that broke the camel’s back. The naturalised indigenous people could no longer take it. They protested as a group at the yamen of Jhanghua County. Not getting a satisfying response, Tatuturo communities joined the eight Pangsoa communities including Taokas East community, Taokas West community, and so on and communities that had used to be part of the Confederation such as Gomach, Salach, Boder, Babuza community of Asoso, etc. to besiege the county and burn down the houses of Non-indigenous people.

The communities that participated in this uprising outnumbered the communities in the Confederation that covered the area around Dajia River, and up to the south of Daan River. This incident was the most violent as well as the last revolt staged by Plains Indigenous Peoples during the Cing rule. While attacking the officials of Cing government, the Tatuturo-led allied forces were not only anti-Cing, but also demonstrated their resentment against the development and encroachment initiated by Non-indigenous people.

The fields and valleys of the entire Central Taiwan were at war for 7 to 11 months. To suppress the uprising, Cing government enlisted 7,000 soldiers and made use of Pazeh community of Lahodoboo to “fighting barbarians with barbarians.” The Confederation met “its Waterloo” and suffered very heavy losses that it could no longer make a comeback. This led to the inability of the Plains Indigenous Peoples in Central Taiwan to withhold the aggression and encroachment of Non-indigenous people. They had no choice but to flee to Iland or Puli to settle down.

We have never disappeared

Tatuturo Confederation was not just a legend

In accordance with the report to the Cing throne, during the Taokas West Community Incident, originally the Confederation was still hoping to restore the power of Tatuturo communities. Though they did not succeed in this “You either fight to win or you die” battle, history moved on with their homeland gradually taken away. Today, three hundred years later, the King of Middag, his descendants, and the Plains Indigenous Peoples from Central Taiwan who settled down in other parts of Taiwan have never been away. They are always here on this island.

Nowadays, Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples are fighting for the reclamation of their own status and reviving traditions and cultures. The communities went through radical changes in history and struggled tenaciously for survival. All that they want now is re-establish their identity as indigenous peoples. Re-establishing identity might not be panacea for sustaining peoples’ lifelines, and the culture they strive to restore has also changed in the course of history. What matters, however, is that the Plains Indigenous Peoples from Central Taiwan can come together again and make young generations aware of who they are.

The offspring of Papora communities of Salach and Tatuturo, Pazeh communities of Lahodoboo and Aoran have actively marked their presence in Legislative Yuan, county governments, community centres, churches, art and literature fields, etc. They want the world to know that the glory of their Confederation is not simply a legend, but also is present now.

The offspring of Tatuturo Confederation have attempted to bring their endangered languages back to life, restore rituals and ceremonies honouring ancestors, resume inter-community communication and visits. They even adapted and put on historical stage plays. These attempts to revitalise indigenous cultures do not only show that the Confederation is making a comeback, but more importantly prove that they have never been gone.

In the past when we discussed the history of Tatuturo Confederation, all too often we ended the story with the crushing defeat of Taokas West Community Incident and fleeing of the Plains Indigenous Peoples, and we always forgot to mention that they were also making history. Maybe the era of the Confederation was gone, but the Sun rises from the east day after day, and tomorrow it still will.

Please note that words of “barbarians” “uncivilized” used in this Issue only reflect to original texts used in the quoted historical literature and they do not contain any discrimination.

─ References ─

翁佳音,1992,〈被遺忘的原住民史──Quata(大肚番王)初考〉,《臺灣風物》,42卷4期,頁145-188。

康培德,2003,〈環境、空間與區域地理學觀點下十七世紀中葉大肚王統治的興衰〉,《台大文史哲學報》,59期,頁 97-116。