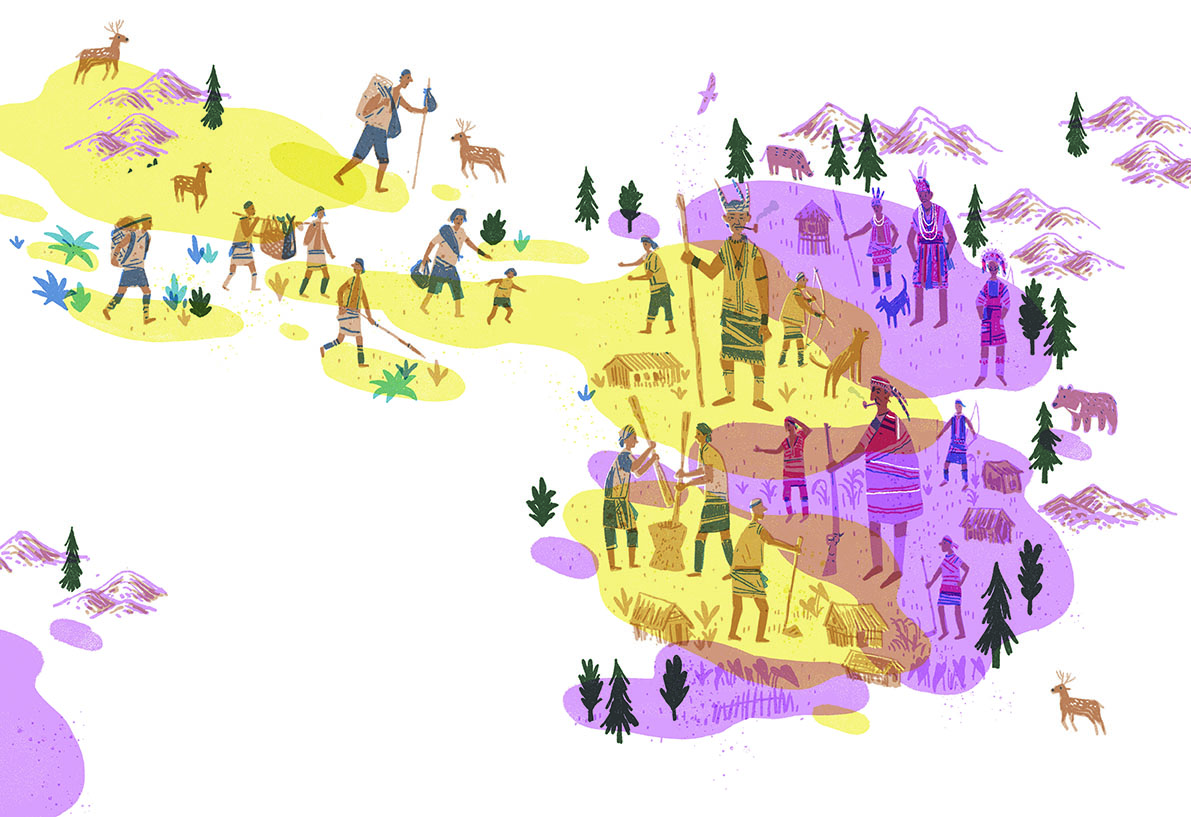

Established by the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People, the inter-ethnic and inter-language Tatuturo Confederation was once a supreme power in Central Taiwan. In the beginning of the 17th Century, when foreign powers arrived at Taiwan they first encountered Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples on the West Coast of Taiwan. Threatened by military force and policies, the Tatuturo Confederation gradually collapsed which was when Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples began their journey of mass migration.

Before the Era of Discovery, Taiwan was unknown to the international community and was thought to be a barren alien land where uneducated indigenous peoples were living extremely close-knit communities. With the exception of a few fishermen and pirates who maintained contact with indigenous peoples on the Southeastern Coast, Taiwan was commonly thought to have no economic or political value. Not much was known about the representative Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People living on the western plain area. Westerners had vague, stereotypical impressions of Taiwan’s geographical topology, with the view that its social culture was undeveloped.

Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People operated their social systems independently based on communities and there had been no outside communications. The Papora people led the Babuza, Pazehhe, Hoanya, and Taokas peoples to build the inter-ethnic and inter-language Tatuturo Confederation in Taichung, Nantou, and Changhua. Although they interacted with outsiders, before the 17th Century, they were not included in the control and social order of foreign rulers. For the Qing Government, they were “uncivilized barbarians (生番)” without any formal education, while for westerners, they were indigenous peoples without a governmental structure to build formal ties.

The Entry of a Barbarian Land

into the World Arena

The originally independent life of the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People began its transformation in the early 17th Century. With the arrival of the Era of Discovery, territorial competition turned fierce and countries around the world began their overseas expansion continuously due to the demands for trade and colonization. Taiwan, thus, became a place of value which was competed for by the world’s super powers, which forever changed the social fabric of this “barbarian land.”

Netherlands and Spain occupied Taiwan’s northern and southern tips respectively on the West Coast. In addition to military suppression, they signed with confederation powers on the Island and forced them to surrender. They set up relevant rules for the identities and rights of “the minority” in their colonies such as inhabitation, taxation, and marriage. Through the introduction of new political organizations, production, exchange (such as cattle farming and business consortiums) and religion, they attempted to change the social culture of indigenous groups. It was the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples who first received the most impact.

Following the policies of the Netherlands and Spanish on the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples, at the end of the 17th Century the Qing Government took over Taiwan officially. The most beneficial policies to stabilize ethnic order were adopted as the official principles. For example, a red line boundary was used to distinguish the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples from others tribes; indigenous peoples were allocated various types of labor work and indigenous household records were built to ensure boundaries with the assistance of the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples. At the same time, indigenous peoples were encouraged to use Non-indigenous family names and learn Non-indigenous texts, and a special administrative agency was established to handle indigenous affairs.

These layered managerial strategies for ethnic groups aimed to avoid deterrence towards the Non-indigenous people’s settlements, as well as to gradually change the lifestyle and cultural values of indigenous peoples for the purpose of central control. The Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples were gradually neutralized and transformed from “uncivilized barbarians” to “civilized barbarians (熟番)” who paid taxes and observed Non-indigenous customs.

The Mass Migration Effects Of The Non-indigenous’ Exploration

Force On Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People

The Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People made their living through shift cultivation and hunting. When the soil was depleted, they discarded the old farm land and moved to a new area and settled there. The Tatuturo Confederation was like scattered political sovereignty in which each community maintained its own independence. Even when they moved to look for more fertile land, they settled down at a certain distance not far away and did not invade other ethnic groups. Generally, before the Non-indigenous people’s settlement in Taiwan, the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People kept their way of living by moving on a small scale within a certain distance to look for more fertile land.

The Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People did not base their principle for land utilization and power with the ownership concept we hold in modern times. Instead, power served as the guidance to determine land ownership. But, after many Non-indigenous people with strong land ownership concepts came to Taiwan, this situation changed. The Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People living on the West Coast felt that their living space was compressed and in order to survive, they began a group migration. There were two types of migrations. First, they migrated to barren areas where few Non-indigenous people lived, but only a few engaged in this type of migration and it was undertaken by small communities. The other type of migration involved crossing the boundaries the Non-indigenous people were restricted to enter by the Qing Government. This type of migration was a huge movement, made up of many ethnic groups. At the same time, this movement also suppressed indigenous peoples who were forced to migrate, and it brought more social impacts on to them.

Forced by foreign powers, the Tatuturo Confederation in Western Taiwan worked very hard to negotiate with the Netherlands and Spanish in order to maintain its independence. It fought against Koxinga and the Qing Government. But, threatened by the military, policies, and settlement of the Qing Government, it finally collapsed. Due to the gradual invasion of the Non-indigenous people in settlements, the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People were forced to migrate later.

The first group of Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People that began big migration was in Central Taiwan. As shown in historical literature, there were four big migrations of Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People, and among them, two were initiated by those living in Central Taiwan.

In 1804, the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People in Central Taiwan collectively migrated to Kavalan (now Yilan), led by Pan Hsien-Wen (the leader of the Lahodoboo Community of Pazehhe). However, because Non-indigenous people had long settled here, only some Plains people left and lived outside Balisha while the rest returned to their original residence. The second big migration occurred in 1823, when the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People in Central Taiwan collectively migrated to the Puli Basin. Besides a few from Hoanya and Taokas, other groups of Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People in Central Taiwan participated and this migration movement resulted in the extinction of the Pu and Mei Indigenous Peoples.

In 1829 and 1840, the Kavalan people originally living in Yilan were also forced to move to Eastern Taiwan due to the Non-indigenous people’s extend territory. They respectively went from Suaou to Kila Plain (nearby Hualien Harbor) or rafted to Lilang Port (now the foot of Meilun Mountain in Hualien) to build six communities including Liyuan, Zhulin, Wunuan, Yaoge, Qijie and Tanbing. They migrated southbound to Tabalang. Certainly, these migrations invaded the original living spaces of Atayal and Amis people.

History of

‘Barbarian Enlightenment’

Interestingly, even though the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People in Central Taiwan strongly resisted foreign powers, the Lahodoboo Community of Pazehhe was indeed an important ally of the Qing Government. At the end of Zheng’s rule, along with the decline of the Tatuturo Confederation, the Lahodoboo Community gradually developed its strength and migrated to Dachia River and Datu Mountain. Even in the era of Emperor Kangxi, when there was the Tunxiaoshe incident of Taokas, the Qing Government worked closely with Lahodoboo Community of Pazehhe under its policy to “Fight Barbarians with Barbarians”. The Lahodoboo Community of Pazehhe was thus given the Non-indigenous’ family name “Pan.” Pan families now living in Central Taiwan are therefore more likely to be descendants of the Lahodoboo Community of Pazehhe.

In fact, before the interruption of foreign powers into the indigenous community, the integrity of community life was vital to the survival of indigenous peoples. Faced with competition from diverse ethnic groups, the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples’ life styles changed a lot. The Non-indigenous’ “family values” gradually spread to these communities, as did social statuses such as fame, land, and family reputation. These became goals of competition for some indigenous groups, and the Lahodoboo Community of Pazehhe significantly changed their life style. To some degree, the Qing Government achieved its ruling goal of “barbarian enlightenment,” and the indigenous peoples were looking to compromise under this cultural impact. Ironically, although Pazehhe sided with the Qing Government, it did not escape the fate of migration. Because of weaker power and sovereignty as well as the fast speed of the non-indigenous people’s settlement, its living space was threatened and in 1804, its people were led for migration.

From the past to the present, the migration of ethnic groups and changes of life style were in a continuous process. Evidence can be seen in historical textbooks and collections at museums, as well as in things hidden in our lives such as place names in Central Taiwan like Tatuturo, Dachia, and Shuishanlien, which were translated from the language of the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People. In addition, we still use the utensils and family names of our friends related to the historical vicissitudes of the 17th Century. These historical records and proofs have become important clues for us in our quest to explore and restore the culture of the Taiwanese Plains Indigenous People.

In conclusion: From the colonial conquests between the Netherlands and Spanish in the Era of Discovery, Ming Zheng, the Qing Empire, the Japanese Empire, or even from 1945 until now, cultural deprivation has been repeated. Since the 17th Century, Taiwan has developed as a bigger entity of common fate, encountering ethnic conflicts, cultural integration, resource exploitation, and the migration of 2 million mainlanders to Taiwan with the relocation of the National Government in 1949. Past historical revolutions and developments complicate and diversify the cultures that we have today, and divide opinion. . We need to carefully examine the sorrows and helplessness of the ancestors of our land.

As taught by history, we need to explore our origins by starting with indigenous history!

Please note that words of “barbarians” “uncivilized” used in this Issue only reflect to original texts used in the quoted historical literature and they do not contain any discrimination.

─ References ─

潘英,《臺灣平埔族史》,臺北:南天出版社,1996年。

洪麗完,《熟番社會網絡與集體意識:臺灣中部平埔族群歷史變遷(1700-1900)》,臺北:聯經出版社,2009年。

白棟樑,《平埔足跡:臺灣中部平埔族遷移史》,臺北:晨星出版社,1997年。