In the past, the paths throughout the Payuwan Community were inter-connected by stairs paved with stone slabs. These paths, surrounded by taro plants, shell gingers, lilies, and marigolds along the way, will finally take one to the highest point of the village—the former site of the elementary school, where the memories of the Payuwan residents are preserved.

In the early days, when there were no refrigerators, the Paiwan people smoke-roast fresh taros for ease of preservation. Apart from a kind of staple, the resulting dried roast taros, or “aradj” in Paiwan, also served as merchandise to be traded with plainsmen for salt and sugar that could not be produced in the mountains. The stir-fired aradj with sugar makes a favorite snack for kids.

To prevent taros from scorching while being roasted, people would climb up the oven to turn them over.

Legend has it that the Paiwan people had been racking their brains on how to roast taros. It was not until one day when a man saw his wife squatting on the hillside with her private parts exposed that he was inspired to invent the stone oven made of slabs.

During the colonial period, when the Japanization movement was implemented, it was compulsory that people pay respect to the emperor and speak only Japanese, the national language of the time. This “National Language Monument” is the heritage that bears witness to this past.

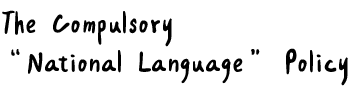

In 1974, the entire Payuwan Community was relocated except for a village senior who refused to leave and chose to stay in the mountains. In August 2009, when Typhoon Morakot struck Taiwan, the old man was left unaware of it due to the lack of telecommunications access. He simply stayed in the house listening to “the howling of the entire world.” A few days later, when the storms had finally stopped, his son returned home to see if his father was safe and sound. Not expectant, he was surprised to find that the old man was still alive. The two cried and hugged each other.

Sericulture, or the technique of silkworm farming, was first introduced to the village as a sideline in 1932 during Japanese rule. In the early days, the crops grown in the village were mainly staples for daily consumption. The only use of silk was to trade for money. The introduction of sericulture has transformed the villagers’ mode of trading from bartering to monetary transactions.

Taken in the 1950s, this photo features a woman wearing a cross, implying that a funeral is going on in her family. From this, we can see that the Paiwan mourning shawl on the occasion of funerals has been replaced by the cross, a sign that symbolizes the penetration of Christianity into the community.

The unique twin-pipe polyphonic nose flute is composed of the flute pipe with finger holes (used for the main melody) and the drone pipe (without holes) bound together with rattan. The instrument is mainly used by a man as a means to express his affection and feelings for, or simply put, to pursue the woman he is fond of. It is also played to mourn the death of honorable seniors or warriors who have made great contributions to the community. Traditionally, only males are allowed to play the nose flute. However, to ensure that their unique nose flute culture will not be lost, Mani's grandfather makes an exception to teach her how to play it.

鼻笛發出的聲音很像百步蛇攻擊前的吐信聲。

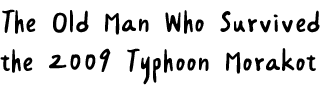

This is the last official herald, or “representative,” recognized by the community leader of the village. When the community leader wants to talk with headmen of other communities, usually he will not go for himself. Instead, the herald is sent to convey the message on his behalf in the first place. In Paiwan society, the herald ranks as a “warrior,” and is allowed to wear hawk-eagle feathers bestowed by the chief. However, since this title is specially granted to the herald alone, it cannot be passed by inheritance.