Setting out from Provincial Highway 18 at the foot of the mountain, passing by the various signage and local specialty stores featuring Alishan, the winding road into the mountain expands before us. It is the road tourists are eager to embark on, and the route of migration the Tsou people took over a century ago, deep into the mountain.

With a little over 6,000 in population and ranking 10th among the 16 official indigenous groups in Taiwan, the Tsou people is mainly found in Alishan Township in Chiayi and Xinyi Township in Nantou. The layering ranges add a mysterious veil to this group with a small population. However, before “becoming” a mountain indigenous group, the Tsou ancestors used to reside in Anping, Tainan, where they hunted the Formosan sika deer for the Netherlands and left behind the geographic name ca’aham?. During the Koxinga Period, with the influx of Non-indigenous people into Taiwan, the Tsou people first retreated from the coast to Veoveoana Community at the foot of Alishan before further migrating into the mountain during the Qing Dynasty, forming the two collective communities of Tapangx and Tfuya.

When the Japanese people occupied the islands of Taiwan, the Tsou people decided to co-exist in harmony with the Japanese. The Japanese colonial government introduced to Tsou indigenous communities education, agriculture, and construction methods, fostering the first generation of indigenous elites with modern education. For the Tsou people, the Japanese might have controlled rigorously the forestry resources, but still allowed them considerable autonomy in how they led their lives. When the Nationalist Government came along, however, everything changed.

In the early years after the war, everything was controlled, even the collecting of jelly-fig required application to do so. Tsou elite Uongu Yata’uyungana, who received education via the teacher’s education program and was educated on agriculture improvement, bravely proposed the idea of “mountain indigenous self-government” during his time as the township mayor and the establishing of the “Niahosa collective farm”. He noted that their development in the mountain over the past century had led to a population increase in both collective communities, but they had no extra lands to farm on. Therefore, he applied to the State for reclamation and reorganized the collective communities according to their clans. Sending the clans into undeveloped areas in the mountain in groups, the new areas they relocated to were named later Saviki, Niahosa, and Chayamavana respectively.

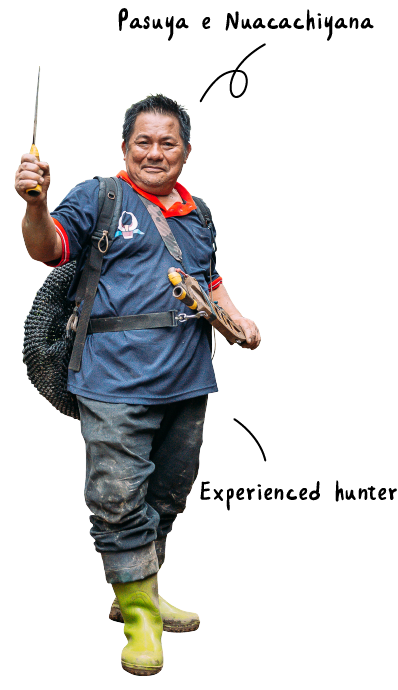

The hardship of reclaiming new lands coupled with the political persecution suffered due to the idea of self-government proposed by township mayor Uongu Yata’uyungana during the White Terror, left the communities overshadowed with fear and endured government monitoring for a long time after, which only slowly faded after the lifting of the martial law. As modernization was introduced to the communities, roads were paved and electricity connected, changes occurred in traditional agriculture, farming, language, and culture, and many had to leave the community to work in the city to make a living. About 20 years ago, the idea of passing on the culture blossomed and Pasuya e Nuacachiyana, who has been greatly influenced by the older generation began operating a Warrior Camp that consisted of one-day hiking, turning the forest into a classroom to teach the traditional lifestyle and knowledge of the Tsou. In 2018, the community development association established the Carving Workshop with local youth to revitalize traditional culture, and Niahosa Community began developing programs featuring the hunter’s culture to shape the indigenous identity for their land and children.