Hunting, agriculture, and fishing are the various sources of food for indigenous peoples. The forestry wisdom and ethics of life of the Tsou are displayed by the tangible tools and intangible culture.

When an animal steps on the trigger, the crossbow will shoot an arrow straight into the heart of the animal. In the old days, boundaries of the clans’ hunting grounds were evident, there were no trespassers and owners knew where their crossbows were placed, and there would be no accidents. But nowadays with things different, to prevent accidentally hurting others, the Tsou no longer uses the crossbow.

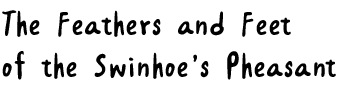

The Tsou language for the Swinhoe’s Pheasant is toevos

The Tsou language for the Swinhoe’s Pheasant is toevosu, meaning “the true bird”. When the Swinhoe’s Pheasant is caught, they will save two parts: the tail feather, which can be used as a headdress, and the feet, which are dried, tied and hung. Both are signs of the hunter’s capability.

We can wear up to 12 feathers in the headdress, 4 from the Swinhoe’s Pheasant (2 black and 2 white), 2 from the Blue Magpie, 2 from the Crested Serpent Eagle, and 2 from the Mountain Hawk-Eagle. We can only wear the feathers of the birds we caught, and even if we caught more we can’t wear more. Usually, we wear 6 feathers and never more than what our elders wore.

We can wear up to 12 feathers in the headdress, 4 from the Swinhoe’s Pheasant (2 black and 2 white), 2 from the Blue Magpie, 2 from the Crested Serpent Eagle, and 2 from the Mountain Hawk-Eagle. We can only wear the feathers of the birds we caught, and even if we caught more we can’t wear more. Usually, we wear 6 feathers and never more than what our elders wore.

The earliest bows were made of wood, but since bamboo multiplies fast and is extremely elastic, many tools later used bamboo instead. The length of the bow generally does not exceed one’s height. If the bow is too long, it can easily get stuck amongst the branches when moving in the mountain, which can cause great inconvenience.

The arrow point comes in two shapes: one is the arrow point shape, mainly used for large animals such as the boar. It can penetrate deep into the heart and cause the animal to bleed to death. The other is the three-pronged, mainly used to hunt small animals such as the flying squirrel, masked palm civet, squirrel, and bamboo partridge. Once they are shot, the arrow gets stuck in the body and cannot be easily shaken off. The animals cannot run far dragging the arrow behind them.

Before iron became accessible, the entire arrow was made with bamboo. The ones made with the skin of the Arrow Bamboo were extra tough and sharp.

Of all indigenous peoples in Taiwan, only the Tsou add feathers to the nock to help the arrow fly further with better stability, and we prefer the wing feather of the female Swinhoe’s Pheasant, the male feather is too thick.

Of all indigenous peoples in Taiwan, only the Tsou add feathers to the nock to help the arrow fly further with better stability, and we prefer the wing feather of the female Swinhoe’s Pheasant, the male feather is too thick.

In the former days, hunters would bring the head of the animals for the elders to assess. The elders would close their eyes, feel the teeth of the animal, and determine by the abrasion of the teeth the age of the animal. The younger the animal, the sharper the teeth, elders would acknowledge the hunter who scored young animals. After the assessment, the hunter will debone the meat and present it to the elder along with some wine, which is a form of sharing as well as paying for the assessment.

✦Tube: Bamboo shrimp tube with a notch at the opening to easily remove the shrimp from the spear, convenient for single-hand operation.

✦Spear: Iron spear with prongs brought close to better catch the shrimp.

✦Wooden box: Functions much like the goggles, when the waves are big, it can be difficult to see into the water, press the wooden box onto the surface with the glass side down, and the hunter can easily see into the water.

The shrimp comes out after it gets dark, and without artificial lighting in the old days, they would tie up dried silver grass in bunches, and place them by the riverside during the day at intervals of 50 to 100 meters. By night, they will light the torches to shine on the river, and that is lighting for shrimp fishing. By alternating the gap between the bamboo, you can adjust the size of the fire.

This is a mid-sized fish trap, made with Formosan palm, used when there is smaller rainfall and the river is less rapid, roughly around November to the rainy season the following year. Place the fish trap where the riverbed has a height difference and secure it with a rock. This will allow the fish to swim into the trap following the flow, the smaller fish can swim away through the gaps while the larger fish will remain. The trap is usually left in place for one to two weeks.

Traditionally, hunters share their harvest with members of the indigenous community. When sharing fish, they will first categorize the fish into heaps of large, medium, and small. If there are elders present, a few of the largest fish will first be given to the elders as a sign of respect, and the rest of the fish is evenly distributed to everyone on site. If game meat is shared, the loin is given to the person who stabbed the animal to death, while the rest is shared among all those present. Furthermore, people who discover animals caught in others’ traps, help to carry the animals home, or even chance encounters in the mountain, all get to share meat.

Food sharing in the family follows a similar rule. After the poultry is treated, the meatiest parts such as the thigh and breast meat are given to grandparents and young children because they are not good at nibbling on the bone, and the rest is shared between the parent generation. However, with the refrigerator introduced to the indigenous community, food preservation became easier and the traditional culture of food sharing gradually declined.

If there are relatives in the community that cannot hunt, the hunter will make sure to share meat with them, which will be reciprocated with fruits and vegetables.

In addition to agricultural products such as bamboo, tea, and camellia oil, there is a group of indigenous people dedicated to restoring native crops on Alishan. Yumi e Yakumangana, the owner of Taso ci cou Organic Agriculture Development Association, grew up away from the indigenous community. Wanting to verify the traditional farming method of “growing the crops well without fertilizer”, and hoping to restore the Tsou’s native crop, she returned to the indigenous community over a decade ago to practice Shumei natural farming. Using no pesticide nor fertilizer, her farm currently has the largest variety of crops farmed with Shumei natural farming.

Taso ci cou is the Tsou language. Taso means “strong”, ci is a particle, cou means “man/person”, Taso ci cou means “strong Tsou person”.

Looks similar to red mung bean, it is the favorite food of the Tsou elders. Yumi e Yakumangana accidentally came across a native species and began its restoration. Traditionally cooked with rice, or in spare rib soup with Adlay millet and pigeon pea.

Native Adlay millet, remove the skin and you have brown Adlay millet.

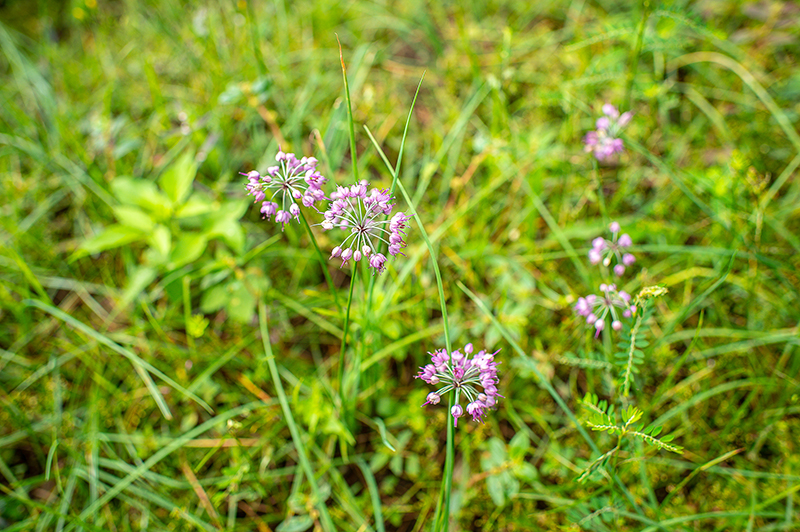

Functions as a sterilizer, extremely popular during the pandemic.

Native sweet potato species, white or purple white in color.

Come in black and red colors, native pigeon pea species is light grey and the only species with a fragrance. Mostly used in soups.

Aka natural thickening flour. Wash, add water, and press, extract and dry the settled starch, and you have Berumuda arrowroot flour. Berumuda arrowroot is one of the dietary sources of Gerson Therapy and is used by many cancer patients. It can also be used to make liang gau jelly and tapioca pearls.

In addition to the above crops, the farm also grows wild bitter melon, turmeric, waterleaf, winged bean, creeping foxglove, and yuca.