The Pazeh legend has it that the people are descended from Maqiyowas, who came come down from heaven to settle and had offspring in the plains of central Taiwan. One day, a flood came and inundated the homeland of the Pazehs. Almost the entire village was killed except for Savung Kaisi and Vana Kaisi, a sister and brother who fled to the mountains and survived the disaster. A few days later, when the flood receded, the couple resettled in Fuluton (today’s Fengyuan in Taichung), got married, and had a daughter and son. They cut their children into small pieces and turned each piece into a person. These people was scattered to the four winds to produce offspring, forming the four earliest communities of the Pazeh people: Pahoropuru, Dyaopuru, Lalusay, and Auran.

Before the Non-indigenous people from China came to Taiwan, local indigenous peoples were generally able to retain their territories and space for living despite some occasional struggles over interest and power. During the rule of the Zheng clan and the Qing dynasty, however, the authorities enticed the Pazeh to cede their land in exchange for irrigation water✱ and employed the strategy of “letting the barbarians fight it out among themselves✱,” which led them to lose most of their territories and became plagued by constant infighting, respectively. The community was forced to relocate en masse and eventually scattered in Yilan County, Puli, and Liyu Lake.

The Ailan-based Pazeh community in Puli converted to Christianity in 1871, which caused the disappearance of many of its traditional rituals and culture. Yet thanks to the introduction of the Romanized writing system by Western missionaries, the Pazeh language was able to be preserved. The unified religious belief helps to foster the cohesiveness of the community. Although the language was once listed as endangered by the United Nations, the determined and never-say-die people of Pazeh, strive to revive their native language with the church as their core base by preserving it in written form and using it to tell their stories.

✱In the Qing dynasty, the Chinese interpreter Chang Ta-Ching funded the construction of the Huludun Ditch (formerly known as the Babuza Ditch) in today’s Taichung Plain to facilitate irrigation and traded the water with the Pazeh people for the ownership of their land.

✱The Qing government used the power of the Pahoropuru Community to quell the resistance of other Pazeh communities.

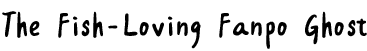

There was a Pazeh man who went fishing in the river at night when fish tended to come out to feed. Every time he dropped the catch into the bamboo basket, he felt that something seemed to be going on inside. But he did not check it because of the poor visibility at night. Upon returning to the village, he emptied the catch out of the basket for inspection, only to find that all the fish had turned into stones. He knew immediately that this was the spell cast by Fanpo Ghost, an evil sorcerer who practiced black magic. He turned to the shaman from the village who also possessed magical power for help. “I beg you to stop playing tricks on our poor fellow man, whose catch is no easy gain. You may leave since you’ve filled your stomach,” said the shaman to Fanpo Ghost. Then, with a wave of the shaman’s hand, Fanpo Ghost flew away, and the man’s catch would never turn into stones again.

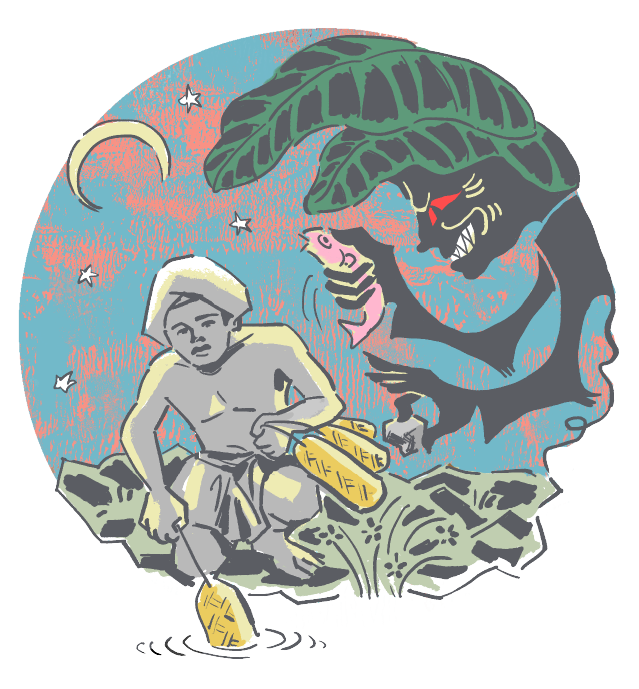

A granny in the village planted a tall mango tree by the earthen wall in her backyard. Every year the tree was heavily laden with fruit, attracting hungry kids to steal the mangoes either by hand or by throwing stones to knock them off the tree. But stones that missed the targets would break the roof tiles, causing the roof to leak on rainy days. These naughty kids who would not listen became a headache to the granny.

One day, the granny heard a child crying behind the house. She went to the backyard to find that a kid was clinging to the tree, unable to break free. He was so frightened that he was crying his eyes out. Upon seeing this, the granny recited a spell to unbind him from the tree. The naughty kid dashed away as soon as he was freed.

In the village lives an old man who possessed magic power. Every morning, he would sit under the eaves of his house and watch people passing by. When kids went past his home on their way to school and saw him, they never failed to greet him with great courtesy, for if they did not do so, they would be punished. One time a kid passed by him uneasily and forgot to give a greeting. Then something weird happened. The kid’s hair grew more and more curly as he traveled on. When he came home from school, his family knew immediately that it was the magic cast by the old man for his impoliteness. It was not until they turned to another granny from the village to help undo the spell that the kid’s hair became straight again.

There was a man in the village who could cast spells and was nicknamed “A-Chung the braggart” because of his love of bragging. One day, he visited one of his relatives and ate with the family. During the meal, he played a trick by keeping the chopsticks upright in his palm. They would not drop no matter how he flipped his hand as if they had been glued to it. A-Chung’s nephew, who was sitting at the table, was very amused by his trick.

One day, the nephew asked A-Chung to teach him to cast spells. Upon hearing the request, the braggart put on a solemn face and rebuked him, “Casting spells isn’t something that can be taken lightly. There are many taboos, and one must pay tragic prices if he wants to master it, including the loss of posterity, suffering from serious illness, and even falling into poverty for the rest of his life. The abuse of spells will not only hurt you but also harm others. Therefore, I can’t teach you that.” The kid did not truly understand why he was scolded, yet he was still amazed by the Pazeh spells even though he had no chance to learn about them.