The Taiwan Plains Indigenous Peoples were formerly known as “civilized aborigine” in the Qing dynasty and “Pingpu peoples” during the Japanese rule, respectively. Throughout their history, however, they have lived so close to the majority Non-indigenous people and were even assimilated into the mainstream society that they have lost their indigenousness, with their identity gradually fading from people's memories or being ignored intentionally. Yet the Pazeh people based in Ailan, Puli, are still striving to preserve their indigenous culture despite their cross-ethnic lifestyle.

We all know that most mountain-based indigenous peoples and Hakkas developed the habit of preserving food with salt in the early days without refrigerators. But few people are aware that the highly sinicized Taiwan Plains Indigenous Peoples also have a food culture of pickling.

Talu Abuk used to work in a restaurant as a chef. Now he is devoted his excellent culinary skill to the “Pinialay mupuzah Pazeh a reten” Cultural Park. He combines his cooking knowledge with ingredients gathered from the mountains and local crops from Puli to re-present authentic Pazeh home cooking.

Pickle stir-fried pork with glutinous rice, rice wine, and salt to let it absorb the fragrance of rice while diluting the flavor of rice wine. It takes only two weeks or so before the dish is ready to eat.

Like the Atayal and Amis, the Pazeh also have the habit of making fermented raw pork. The flavor can be adjusted to suit one’s personal preference.

Though small in size, the fragrant manjack fruit must be boiled over high heat first and then simmered at low heat for four hours.

Fermented fish is a well-known dish in Atayal cuisine, but don’t think that the Atayal is the only indigenous people who handle fish this way. ✱

The Pazeh-style fermented fish is typically made with salt, rice wine, and glutinous rice✱. First, stir-fry the uncooked rice until more than 80% of it turns brown. Then dip the fish into the mixture of rice, rice wine and salt. Leave the fish to ferment for three months before it is ready to eat.

✱The Amis are connoisseurs of wild plants who eat a wide range of them. Other indigenous groups, though not consuming as many kinds as the Amis do, also have their unique ways of eating and cooking wild vegetables.

✱White rice will do, but glutinous rice is sweeter in taste and thicker in texture.

Pickle bamboo shoots with fermented beans(lekko), salt, and a little bit of sugar and leave the mixture to ferment for six months or so to produce the best flavor.

The richly flavored pickled bamboo shoot can also make a good soup base.

Alianthus prickly ash is a spice plant commonly used by Taiwan indigenous peoples in their cooking. This dish features a mixture of tofu and alianthus prickly ash topped with ground peanuts to add a bit of texture.

Thai basil is also a culinary herb commonly used by the Pazehs to add flavor to simple dishes.

The most famous crop of Puli and a common vegetable on the dining tables of the Pazeh in Ailan.

The vegetable ferns and bird’s nest ferns offered in the restaurant are grown by Daway locally. In the past, they used to be flavored plainly with salt water, while nowadays, they are mostly stir-fried or blanched and then flavored with seasoning.

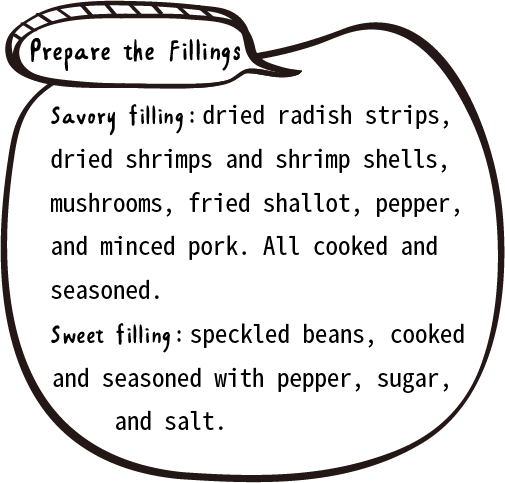

The Pazeh New Year falls on November 15 annually. On this day, such festive events as singing the song of Ayen, Tâng‐Lô‐Bú (hitting gong and dancing), Maazazuah (marathon as a rite of passage), and Paarazam (cross?holding dance) are held to celebrate the autumn harvest. Every household would gather together before the New Year to prepare umu rice cakes as a food offering to their ancestors, thousands of which are made each time. The dish looks similar to the herbal rice cakes commonly consumed by the Non-indigenous people. Try your hand to make one following Adoor's demonstration to see how they are different.

Soak glutinous rice in water for six hours. Then grind the rice into rice pulp and dehydrate it with a machine. Mix the clumps with blanched mugwort to make the dough.

Soak glutinous rice in water for six hours. Then grind the rice into rice pulp and dehydrate it with a machine. Mix the clumps with blanched mugwort to make the dough.

We use the leaves of bananas for wrapping, while those living on the hillside prefer Alpinia. It doesn’t matter which one you choose. Just use the material that is close to hand. But banana leaves will add an extra flavor to the umus.

We use the leaves of bananas for wrapping, while those living on the hillside prefer Alpinia. It doesn’t matter which one you choose. Just use the material that is close to hand. But banana leaves will add an extra flavor to the umus.

Roast banana leaves until they can be crumbled by hand. Then cleanse them with water.

Roast banana leaves until they can be crumbled by hand. Then cleanse them with water.

Add an appropriate amount of oil to the dough and knead it. Grab a portion of the dough and wrap the filling into it.

Add an appropriate amount of oil to the dough and knead it. Grab a portion of the dough and wrap the filling into it.

Roll the umu into a long oval shape. Place it on a piece of banana leaf and fold it in half.

Roll the umu into a long oval shape. Place it on a piece of banana leaf and fold it in half.

One must distinguish the front and back of banana leaves when wrapping umus, which is difficult for those who are inexperienced. One is likely to be scolded by older people for wrapping an umu with the wrong side of the leaf.

One must distinguish the front and back of banana leaves when wrapping umus, which is difficult for those who are inexperienced. One is likely to be scolded by older people for wrapping an umu with the wrong side of the leaf.

Steam the wrapped umus for 30 minutes or so.

Steam the wrapped umus for 30 minutes or so.

In the early days when families used to have many children but had few things to eat, the elders would turn whatever food materials available at home into umus to feed their children. Over time the practice has gradually evolved into a Pazeh culinary culture, featuring the umu as a must-have dish in celebration of their New Year.

Puli is a melting pot of the Taiwan Plains Indigenous Peoples, which is home to several subgroups, including Kaxabu, Babuza, and Taokas. The Pazeh, on the other hand, are based in the Ailan area, living next door to the Papora. The two peoples are bounded by the slope of Tieshan Road, with the Pazeh living on the Ailan Plateau up the slope and the Papora at the lower end of it. Many of the churches, schools, and hospitals are located in Ailan because the power of the Pazeh was the more powerful in the past.

There are three Pazeh communities residing in Ailan: Patakan, Aoran, and Lalusai, which are the names of their former settlements around today’s Pengyuan, Taichung.

In the 2000s, the Pazeh successfully constructed a network of cultural revitalization with the church serving as their core base. They have made remarkable achievements in language preservation and have received many indigenous literature awards sponsored by the Ministry of Education. Twenty years have passed, yet the Pazehs have still not been able to break free from the shackles of Sinicization. What is worse, they are faced with the outflow of young people that threatens all the minority indigenous peoples in Taiwan, making the passing on of culture even more difficult. Without these indigenous ethnic groups, would there be a gap in the history of Taiwan? We must strive to o preserve and keep the culture of Taiwan indigenous peoples alive before it is too late. After all, it is these fascinating stories that make the soul of our island.