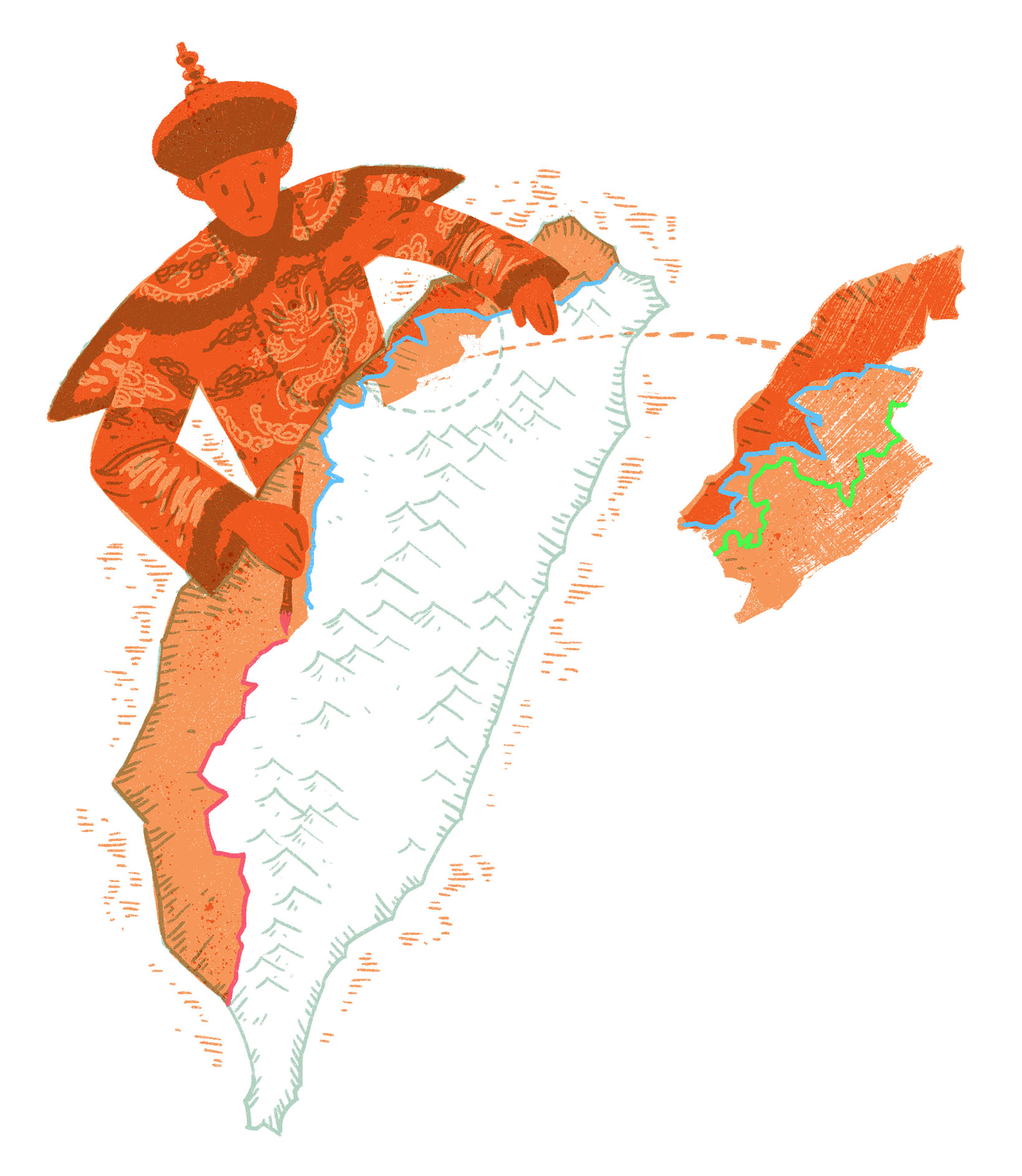

Promoted as the main tourism policy of government, the Romantic Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road has become a newly emerging tourism term. But for the indigenous peoples, on the other side of “being romantic,” this is the boundary where ethnic groups were divided for the invasion of their space of survival as well as the landscape space filled with memories of blood and tears.

In May, 2016, Lee Yung-de, Minister of Hakka Affairs Council, was answering to Legislative Yuan to Legislator Huang Chao-Shun’s interesting question, “The Romantic Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road, and you need to let me know which three roads are.” This question was heatedly discussed afterwards. “The Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road” thus attracted great attention. In fact, there have not been three roads and the Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road is a highway where features “Hakka” settlement landscape.

In May, 2016, Lee Yung-de, Minister of Hakka Affairs Council, was answering to Legislative Yuan to Legislator Huang Chao-Shun’s interesting question, “The Romantic Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road, and you need to let me know which three roads are.” This question was heatedly discussed afterwards. “The Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road” thus attracted great attention. In fact, there have not been three roads and the Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road is a highway where features “Hakka” settlement landscape.

An online article, entitled “Are there really three lines on the Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road? The road is not romantic at all! In Taiwan history, how did Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples began four massive migrations because of the “Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road?,” was written by a Taokas youth, Kaisanan Ahuan, to extend to thinking of ethnic history the from humorous current event. In his article, he mentioned on the Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road, there were several sections marked as boundaries of “Tu Niu Red/Blue Lines” in Qing Dynasty as well as the continuous marketing of “Barrier Defense Lines” during Japanese ruling, “For some ethnic groups, the Romantic Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road presents something they are longing for but for Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples, it is a historical path of blood and tears.”

In fact, the Road was also known as the “Inner Mountain Highway” and it is not completely overlapped with “Tu Niu Red/Blue Lines” and “Barrier Defense Lines” of the historical boundaries between Non-indigenous and indigenous peoples. Furthermore, during the Kangxi period, the boundary lines between Non-indigenous and indigenous peoples were changed in constant and along with the ruling of the Empire, they were adjusted from time to time and used for the function and symbol of ethnic boundary and military. Under the Japanese ruling, scattered defense and industrial roads were continuously expanded and later, they were built as the Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road- the site filled with growth and decline as well as conflicts of Taiwan’s ethnic groups.

The “Romantic Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road” promoted by government aims to promote the 16 beautiful Hakka villages, stories of Hakka settlement with great hardships. But if we look back the past hundreds years, the “Romantic Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road” in the eyes of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples, is not romantic at all and it presents deep sorrows.

Tu Niu barbarian(番) boundaries, barrier defense lines present the Non-indigenous-oriented ethnic issue in history. As the famous words of the Paiwan poet, Malieyafusi Monaneng, when criticizing Lee Shuang-Tze’s “Formosa” lyrics, “Your settlement achievements began from our history of displacement.”

Boundary Division

the Contacting Site of Settlers and Indigenous Peoples

In the “400-year of Taiwan’s Exploration History,” since the 16th Century, settlers from China continuously arrived in Taiwan and had frequent contacts with indigenous peoples. They lived in the “contacting site” from time to time. Mutual interactions were not only limited to economic life, there came force conflict models for gaining resources. Due to this background, there were many tangible and intangible “boundary lines” and various activities were conducted between boundaries.

In 1624, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) entered Taiwan and adopted the strategy “to Rule Barbarians with Barbarians” by asking the surrender of indigenous communities. In 1642, the treaty signed with Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples stated clearly that “Chinese settlers cannot hunt in mountains and indigenous peoples cannot hunt across boundaries.” After Koxinga successfully dispelled the Netherlands and took over Taiwan’s ruling, “the civilian state farm (tuntian) was introduced to expand barbarian lands” for land management. On the boundary area between Non-indigenous and indigenous peoples, “Tu Niu Go” was established. Observatory houses were common “barbarian ruling” measures in the early time.

Since then, Taiwan had the Non-indigenous and indigenous boundaries of “Tu Niu Barbarian Boundaries.” After construction, these boundary lines were concretely built. Due to the increase of settlers, it was common that Non-indigenous people settled across boundaries and there were more conflicts. For more aggressive settlers, they held view of hatred “someone not my race must have a different mentality.” Because of misunderstanding and cultural and custom difference, more conflicts than interactions occurred between Non-indigenous and indigenous peoples. During the conflicts to gain for survival resources, settlers used policies, systems, or organizations to concretely “mark boundaries” between Non-indigenous and barbarians. For indigenous peoples, the contacting site with outsiders has been changed constantly and even shrunk gradually.

Barbarian Boundary Map of Qing Dynasty

Marking for Ethnic Spaces

In 1684, Taiwan was officially include in the territory of Qing Dynasty and a large number of Non-indigenous settlers arrived in Taiwan. They gradually invaded survival spaces of indigenous peoples. More and more conflicts between Non-indigenous and indigenous peoples are seen and there were social turmoil and incidents against the Qing government involving territories of uncivilized barbarians. In order to govern, the government gradually developed policies of barbarian boundaries to limit Non-indigenous people’s settlement to divide activity areas for Non-indigenous and indigenous peoples.

In 1722, one year after the Zhu Yiqui Incident was suppressed , the government marked mountain boundaries because during the suppression, the government was in no control of mountain areas and uncivilized barbarians. Plates were installed at sites where Non-indigenous and indigenous peoples interacted to ban boundary crossings by both sides. Boundary lines followed natural topology such as mountains and rivers. If there were no mountains and rivers, “drainage and soil pile” were used. From Northern to Southern Taiwan, there were 54 plates for the first clear boundary marking between Non-indigenous and indigenous peoples. From Yongzheng to Qianlong period, the Qing Dynasty marked boundaries for uncivilized barbarians several times. Sometimes, drainages were excavated to develop “Tu Niu Go.”

After the Qianlong period, Non-indigenous people began the settlement on the lands of “civilized barbarians.” The Qing government’s attitude changed significantly from the encouragement to prohibition. There was ethnic ruling policy of “inside uncivilized barbarians and outside Non-indigenous people and in between, there were civilized barbarians” indicating boundaries between Non-indigenous and uncivilized barbarians were for Non-indigenous people, uncivilized barbarian and civilized barbarians.

In the Qianlong period, ethic policies of the government were more mature and in addition to plates erected and names of place preserved now, the map, the “Barbarian Boundary Map” of the Empire measured were also the direct evidence. In the Qianlong period, because of “Determining Boundaries for the Prohibition of Crossing Settlement,” four measurements were conducted to clarify lands outside boundaries by marking four colors of “red, blue, purple, and green” boundary lines. Thus, mapping needed to preserve different colors of barbarian boundaries and more colors were added to lines on the map.

Composition of the barbarian boundary map included names of places, illustrations, marks, and landscape drawing and map symbols of image structure to present social situation at that time and tangible facilities equipped along boundary lines such as Observatory houses. The barbarian boundary map presented not only the settlement history of Non-indigenous people but also the history of forced migration of indigenous peoples filled with blood and tears.

From Tu Niu Barbarian Boundaries

to Barrier Defense Lines

In the middle of the 19th Century, the Qing government had no breakthroughs towards governance of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples and Tu Niu boundary lines were measured for the governance. Although during that time, Non-indigenous people on the plains were banned for entering mountains, but they continuously crossed boundaries for private settlements.

The 1874 Mudan Incident was an influential historical event. The Qing government, in order to tighten control, took more active measures for barbarian lands within boundaries. Shen Pao-chen proposed “Open Mountains to Cultivate Barbarians” to gradually lift banning of mountain settlement and the “Barbarian Cultivation” policies included medical care, education, farming, and settlement recruitment. In 1885, Liu Ming-chuan was transferred to be the Grand Coordinator of Taiwan and he began more comprehensive works of barbarian cultivation.

Additionally, in the Qianlong period, to prevent “harms caused by barbarians,” “barrier defense” lines were built along Tu Niu barbarian boundaries by collecting local defense power to form local defense teams to develop the form of semi-official force. Later when Liu Ming-chuan governed Taiwan, it became fully official form and the original Tu Niu barbarian boundaries were transformed in “barrier defense lines.”

The barrier defense system originated from two types of measure for areas that were difficult to govern by the Qing government: settlement and defense. The initial implication was in the area where the government was not able to govern, surrendered civilized barbarians and local power shall handle their relationship with uncivilized barbarians on their own.

In the end of the 19th Century, immature barrier defense lines presented the change of passive attitude towards indigenous governance to active as well as invasion of ethnic spaces and cultures. For Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples (civilized barbarians), they lived originally the buffering zone between Non-indigenous people and civilized barbarians, but due to continuous crossing boundary settlement of Non-indigenous people, they needed to join the settlement with Non-indigenous people without clear distinguishing. Today, we can regard this process as being cultivated by Non-indigenous people.

But in the end of Qing’s ruling on Taiwan, due to the threats of advanced force of western countries, the Qing government had no time to care for Taiwan’s political affairs and the official barrier defense system was gradually abolished. The private force took over to defend boundaries. In 1895, the Japanese ruled Taiwan and was in charge of all official barrier defense lines and barbarian cultivation bureaus of Qing government.

After Japanese ruling, mountain resources were actively developed. Mountain areas in Northern Taiwan with rich wood, coal, and camphor resources became the official target. In order to explore the mountain economic industry, the Taiwan Office of the Governor-General expanded the installation of barrier defense lines by providing subsidies to the private sector as well as tightened police control measure. Barrier defense was transformed into a system under the direct control of the police to deepen management in the areas of uncivilized barbarians and defend people against the Japanese to enter mountains.

The Expansion

of Hostile Barrier Defense Lines

The barrier defense line not as its name indicates is not a line but a zone of semi-military defense installed along natural boundaries such as mountains and water to block communications among communities of uncivilized barbarians. With the advantage over force, indigenous communities were controlled and suppressed.

Unlike in Central and Southern Taiwan or the indigenous peoples who had long contacted with Non-indigenous people, Atayal people adopted more active strategies. In order to prevent them crossing the boundaries, the Japanese amended barrier defense lines left by the Qing government and added wire meshes bells, and aluminum bottles for alert and ban trading between people on the plains and the indigenous peoples to force the surrender.

Barrier defense lines have long been the strategic core of the Japanese for the indigenous peoples. Because the focus of mountain and forest resource development in the early time, the defense function was more important than invasion. After 1902, barrier defense teams were assigned officially and the “Rules Governing the Installation of Barrier Defense Line” were formulated. The groups patrolled lines days and nights and a “Distribution Station” was in charge of two to four observatory houses. The Station, then, was commanded by the “Command Station” of the police equipped with modern military facilities such as hidden shelters, wood fences, searchlight, and land mines to defend uncivilized barbarians and prevent contacts between uncivilized barbarians with people on the plains. Atayal people were often injured or died because of the electric wire mesh and hatred and conflicts between both sides gradually increased.

The expansion of barrier defense lines was initially because of the war between the Atayal and the Japanese. The Qing Dynasty adopted more passive Non-indigenous and indigenous separation policy and due to the exchange process of economy and materials needed for agricultural settlement, the “barbarian boundaries” were gradually expanded while during the Japanese ruling, more active expansion strategies of barrier defense lines were adopted. In the mindset of the colonial government, the “barbarian boundaries” did not separate Non-indigenous and indigenous people but areas ruled or not ruled by the national sovereignty. Therefore, the Japanese attempted to use military force to govern the territories of uncivilized barbarians.

In order to fight against the expansion of barrier defense lines, Takekan and Mawutu Groups of Atayal people in Taoyuan and Hsinchu in 1907 came together with Non-indigenous people, known as “the Takekan Barbarian and Non-indigenous Joint Anti-Japanese Incident.” In 1908, 26 communities in Puli Branch of Atayal also fought against barrier defense lines in Nantou. In 1910, the Japanese began the second “Five-year Barbarian Cultivation Program” and began using force to wage large-scale wars to suppress Atayal. The most well-known one was the “Lee Dong-Shan Incident” fiercely suppressed by the Japanese Governor-General Sakuma Samata in person.

Rethinking of Modernity

Internal and External Thoughts

When we look at Taiwan history from the Non-indigenous-oriented perspective, we only remember the hardship achievements created by Non-indigenous people. It seems inevitable and rational in the context of modernity. Taiwan’s modernity has been created with the special condition of colonial modernity, a critical period for its formation. Colonial modernity presents a complicate historical scene. In addition to the Discovery Era in the 17th Century when Non-indigenous people perceived competition of world resources among super powers, at the same time, we also need to examine first colonization of Taiwan’s indigenous peoples-by the west, Japanese, and Non-indigenous people.

From the expansion processes of Tu Niu barbarian boundary lines in the early Qing Empire to barrier defense lines during Japanese ruling, indigenous peoples were tracked in mountains and forests with deprived resources. Those expansion of barrier defense lines interrupted communications between indigenous communities. In terms of space, this historical division was a dynamic process and a step of colonial modernity that separated others and spread ideology of cultural advancement.

This is also the bloody and cruel part of modernity. When we are chatting pleasantly about the Romantic Taiwan 3rd Provincial Road and the hardship achievements of Non-indigenous people, not so many people would remember the displacement history of indigenous peoples along the road, how we were suppressed, relocated, and assimilated or even our historical memories of wars and conflicts.

Please note that words of“barbarians”,“uncivilized”used in this Issue only reflect to original texts used in the quoted historical literature and they do not contain any discrimination.

─ References ─

Kaisanan Ahuan,〈台三線上還真的有三條「線」,而且一點也不浪漫!台灣史上的「台三線」是如何影響平埔四次大遷徙的?〉,Mata Taiwan:https://www.matataiwan.com/2016/05/25/the-3rd-taiwan-provincial-road/,2016年。

林一宏、王惠君,〈日治時期李崠山地區理蕃設施之變遷:從隘勇線到駐在所〉,臺北:《臺灣史研究》,第14卷第1期,2007年。

伊能嘉矩原著,江慶林等譯,《臺灣文化志(中譯本):下卷》,南投:臺灣省文獻委員會,1991年。

鄭安晞,〈日治時期隘勇線推進與蕃界之內涵轉變〉,《中央大學人文學報50期》,2012年。

陳志豪,〈清乾隆時期臺灣的番界清釐與地圖繪製:以中國蘭州西北師範大學圖書館藏 〈清釐臺屬漢番邊界地圖〉為例〉,臺北:《臺灣史研究》,第25卷第1期,2017年。