Indigenous movements that began in the 1980s have achieved certain results in the existing state institution, and their forms have gradually shifted from a generalized indigenous movement to regional cultural revitalization programs taking place in local communities. As we enter the post-indigenous movement period, the indigenous youth continues to speak out on issues about the land, ways of life, and culture of indigenous peoples, and even about general social problems in Taiwan. "After the indigenous movements, we still have work to do," they say.

The rise of indigenous movements was closely connected to the overall Taiwanese society and historical background of that time. During the Ten Major Construction Projects period in the 1907s, many indigenous people migrated to cities to look for work. They encountered many problems, such as employment problems, insufficient living spaces, and issues concerning discrimination, child labor, child prostitution, and deep sea fishing laborer rights. Taiwan was still under martial law near the end of the 1980s, yet more and more objecting political parties and movements appeared. The idea of making a stand against the ruling government started to spread in society as well, and indigenous intellects experienced their awakening during this wave of movement.

The Tumultuous 1980s:

The Rise of Indigenous Movements

In 1983, Atayal student Iban Nokan, who was then studying at National Taiwan University, collaborated with other indigenous students and published the indigenous magazine Gao Shan Qing (高山青) to raise awareness among indigenous peoples and officially kicked off the series of indigenous movements. The Haishan Coal Mine Incident happened the following year, in which most of the victims were Pangcah miners. The tragedy spurred on the establishment of the Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association, Taiwan's first organized indigenous movement group, with Parangalan as the first chairperson. The Association was the main forefront of the indigenous movements between the 1980s and 1990s. Many indigenous pastors from the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan were also an important force during this period.

The first thing carried out by the Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association was to define the name of the indigenous people. Indigenous peoples in Taiwan were called barbarian (番) during the Qing dynasty and the Japanese Occupation Period, and "Taiwanese aborigines" after the Republic of China government took over Taiwan. These were all names given by the ruling powers. The appearance of the term "indigenous peoples" marks the first time the peoples themselves could decide who they are and how they wanted to be addressed. The Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association focused on name rectification, reclamation of indigenous land, and self-governance. They collaborated with opposing political movements to criticize the party-state system, and offer services to individuals in cities to educate the peoples about their rights while learning more about the oppressed situation of the indigenous peoples.

From Individuals to the Peoples:

The Collective Rights of the Indigenous Peoples

In 1987, the longest martial law period in Taiwanese history ended, and the Indigenous Rights Promotion Association was renamed as the Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association. The Association announced the Indigenous Rights Declaration which listed 17 articles, including the human rights of indigenous peoples, the right of basic living protection, rights of culture, right of self-determination, regional autonomy, self-definition, national policy participation, and the final veto rights to national policies concerning indigenous affairs. This moved the focus of indigenous movements from individual rights of survival to the narrative of the peoples’ collective rights of development.

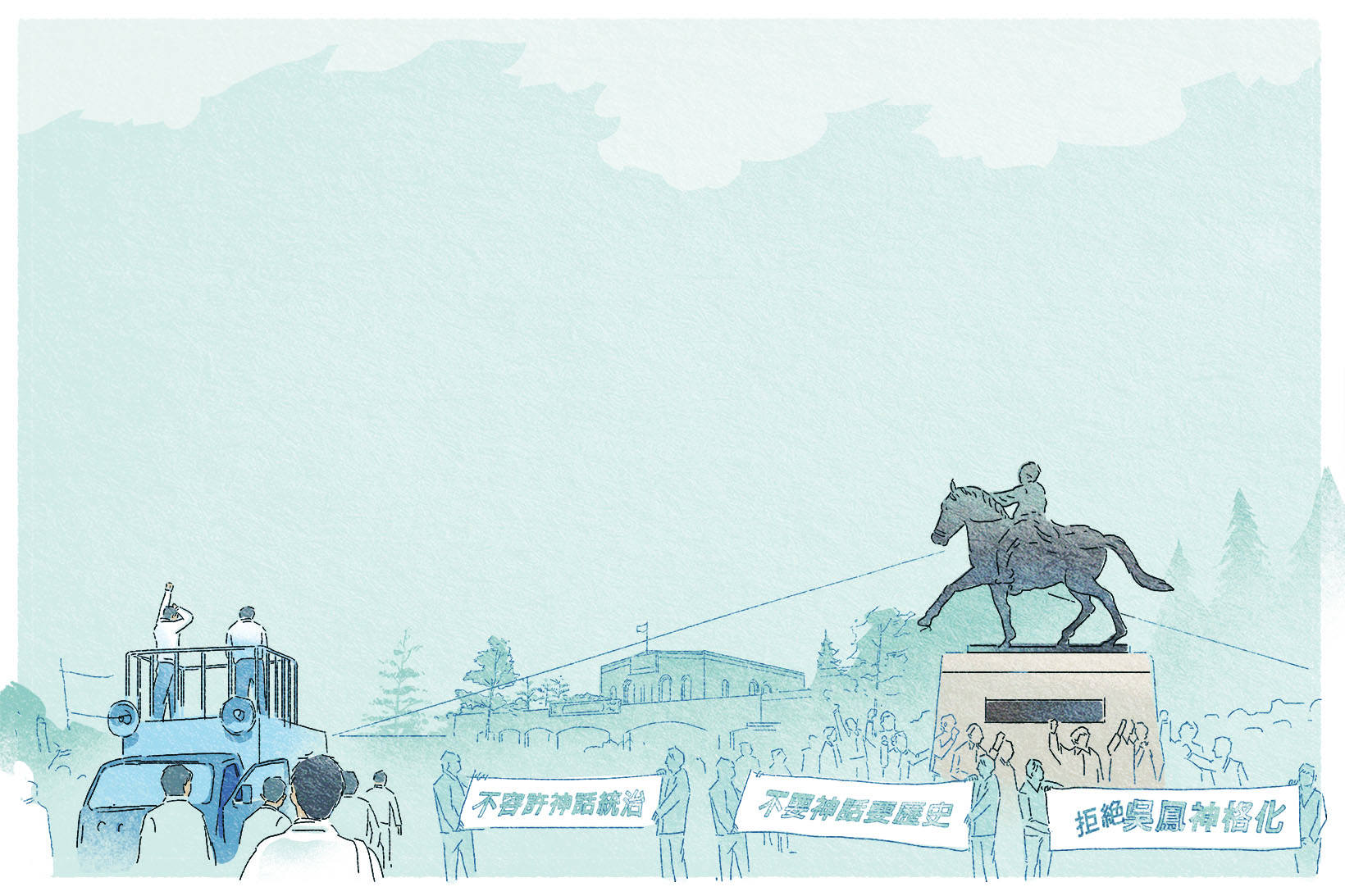

In September, 1988, Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association, indigenous university students, and pastors from the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan held a protest in front of the Wu Fong statue at Chiayi Train Station. They pointed out that textbooks since the Japanese Occupation Period to the Chinese Nationalist Government included the made-up story about Wu Fong which vilifies indigenous peoples. There was another aggressive protest the following year during which protesters pulled down the statue and demanded the authorities to "correct the Wu Fong story".

The four protestors who pulled down the statue were interrogated at Chiayi District Prosecutors Office the following year. Pastor Kavas Takistaulan, a student of the Yu-Shan Theological College and Seminary, insisted on answering questions in his own native language, forcing the court to hire a Bunun interpreter. This is the first record of an indigenous language interpreter being employed for an interrogation process. The public openly voiced their support for the four activists when they were taken into custody. Doctors Chen Yong-xing and Zheng Nan-rong formed the 228 Incident Justice and Peace Promotion Association and decided to organize the annual 228 Incident march at Keelung and Chiayi. For the Chiayi march, they contacted local Tsou communities and planned to jointly show their support of the four detained activists. The government did not want to stir up more trouble and released the detainees with no charges. The government also changed the name of Wu Fong Township into Alishan Township the same year, and announced that the story of Wu Fong will be taken out from textbooks.

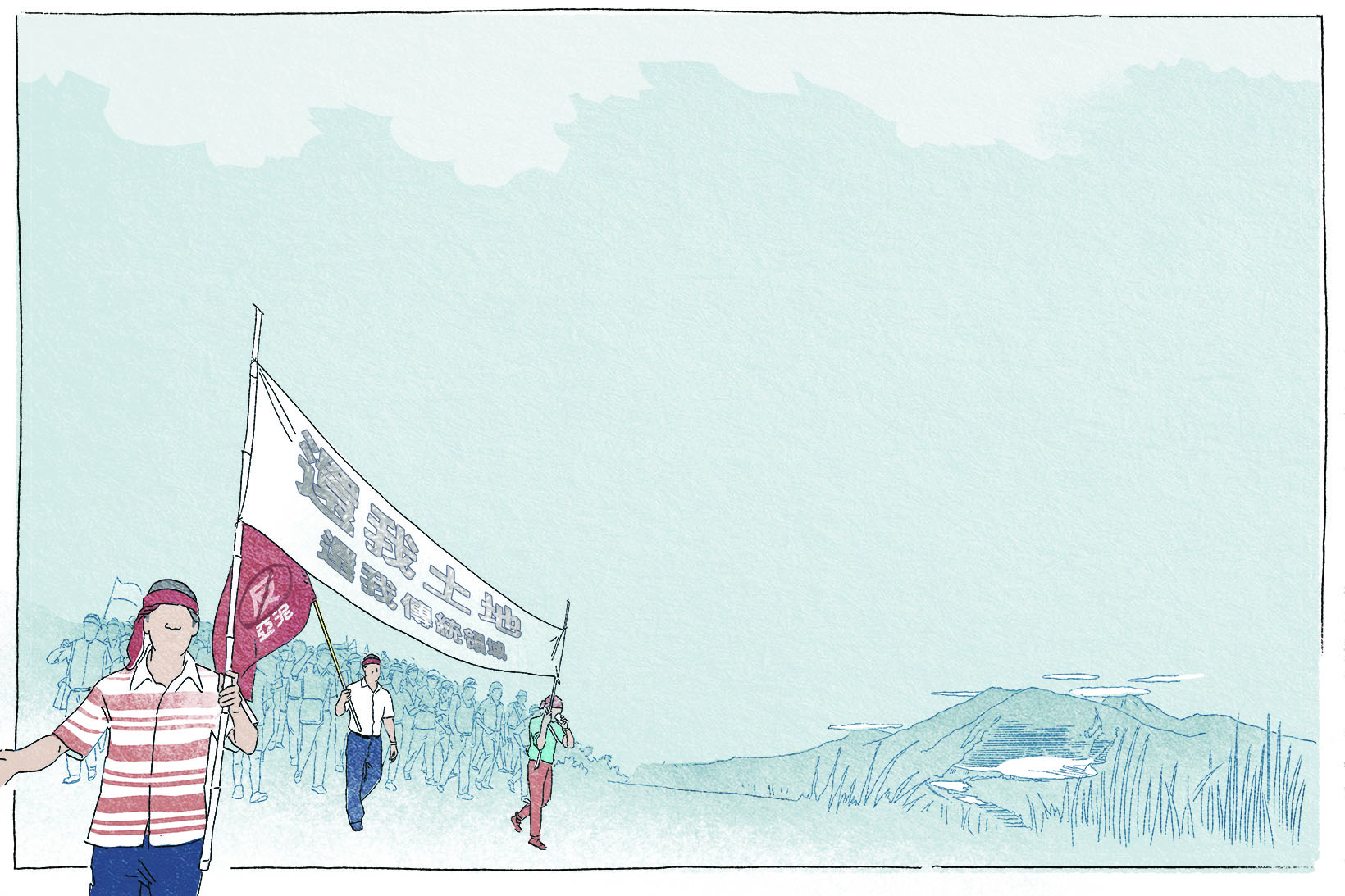

Around that time, the Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association collaborated with other indigenous movement groups and the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan and formed the Taiwan Indigenous Peoples' 'Give Back Our Land' Movement Alliance in 1998. In the same year they organized the first Give Back Our Land Campaign. By 1993, there were already three waves of land reclaiming movements, with two to three thousand participants at each event. This was the time when the early indigenous movements were the most active, and also when the indigenous peoples shared the strongest consensus.

In addition, incidents such as the Constitutional Amendment Movement, protesting against excavating ancestral burial sites in Dongpu, and the Musha Incident Memorial also connected indigenous movement activists closer, regardless of their original community. They started to support each other: the Tao people no longer have to fight the nuclear waste issue alone, and the Majia reservoir issue was no longer only about the Rukai people. Because all indigenous peoples share the painful experience of having their land taken away, their rights of survival violated, and ethnic dignity stripped, these issues led to different peoples starting to work together in indigenous movements.

From Pan-indigenous Movements

to Localized Community Programs

During the mid to late 1990s, some movements obtained their goals, and many activists tried to be elected into office or work in the public sector. These reasons led to the demise of the Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association. At that time there were much interaction between members of the Democratic Progressive Party (DDP) and the Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association. Association members also began to disagree on whether they should work within or outside of the state institution. Eventually the founders of the Association regretfully announced that the Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association has served its purpose for the moment and should be retired. They stressed that indigenous movements should not become the accessory of any political group, the peoples should continue to move on with their indigenous identity, and finally announced the dissolution of the Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association.

At the same time, many indigenous activists began to reflect on the limitations of taking a pan-political approach during the early stages of indigenous movements. More and more people realized that they had overlooked the people in local communities issues. Tiaban Sasala severely criticized the Taiwan Indigenous Rights Promotion Association for leading movements that were associated to Taiwan's democracy movements. He pointed out that the activities were not relevant to the daily lives of local indigenous people and did not improve their general wellness. He further proposed the concepts of "working locally" and "community-centered programs", claiming indigenous activists should "fully give up activities in the cities and return to the indigenous communities". Sasala started Indigenous Newspaper. He compiled and explained myths from different peoples and encouraged community youths to care about community public issues.

The concept of community-centered programs encouraged individuals to revive local culture in indigenous communities everywhere, such as reintroducing sacred rites and local traditional groups (Youth Groups, for example). Local energy began to grow rapidly and developed a trend of indigenous nationalism among all communities seeking autonomy. In terms of self-identification among indigenous peoples, there were name rectification movements for the Tsou, Truku, Thao, and Kavalan. In rights of survival space, the Bunun were protesting against Yushan National Park, and the Atayal were protesting against Shei-Pa National Park. There were also other movements organized by the indigenous peoples themselves against Maqaw National Park and Asia Cement Corporation.

Gradually, indigenous movements were no longer only initiated by the urban elite and pan-indigenous movement groups. More local forces were getting involved. If it weren't for the first indigenous movements, Taiwanese indigenous peoples may not realize that they need to focus and combine their energy, work together, acknowledge their differences, and eventually bring the passion back to local communities. Spreading from single points to the entire nation, this is the diverse and beautiful achievement of indigenous movements.

After Indigenous Movements:

Gradually Seeing a New Dawn for the Peoples

After the indigenous movements, we have gradually seen results. The Third Constitutional amendment in 1994 introduced the term "indigenous peoples" into the Constitution. In 1996, the Council of Indigenous Peoples was established under the Executive Yuan. Taiwan finally had an official indigenous agency in the central government, and national resources could be used to revive local culture in indigenous communities and operate local communities. In 1998, Taiwan passed the Education Act for Indigenous Peoples; and the year 2000 saw the first change of ruling parties. The then-president Chen Shui-bian signed "A New Partnership Between the Indigenous Peoples and the Government of Taiwan" with the indigenous peoples, setting the foundation for a relationship of nation by nation, meaning the Taiwanese government and the indigenous peoples are equal political entities. This is the first time the central government viewed indigenous peoples as equals, not receivers of welfare or minority groups.

Although movements outside of the state system seemed to slow down, they did not disappear, but changed forms. Indigenous intellectuals returned to their communities to empower communities. Some continued to promote the core values of indigenous movements by discussing national policies, drafting indigenous peoples' rights related regulations, and proposing initiatives. Within the state system, politicians who identify as indigenous continue to push for relevant reforms. The Indigenous Peoples Basic Law was passed in 2005, putting the subjectivity, space sovereignty, and right of self-determination of indigenous peoples into law. And this has become the most important foundation for modern indigenous movement discussions.

The Smoke Signals are Lit Once More:

Indigenous Movements Carry On

Although we had reached certain levels of success in the early phases of indigenous movements, but the survival issues indigenous peoples face cannot be changed overnight. There are still a lot of conflicts going on between the state and indigenous traditions.

The same year the Indigenous Peoples Basic Law was passed, many incidents happened: in the Qalang Smangus community in Hsinchu County Jianshi Township, the residents held a community meeting and decided to bring back some fallen beech trees that were uprooted during the typhoon to the community for decoration purposes. But the people were prosecuted by the Forestry Bureau for stealing. Hanxi Community in Yilan County fought against the Water Resources Agency for seizing water rights, and Sanying and Xizhou Communities, which were located in urban areas, were forced to relocate due to land development. These incidents provoked fury among the indigenous community. Yet it was the incident that happened at the end of 2007 that ignited the conflict: during the Grand Hunt of the Katripulr People in Taitung, the indigenous hunters went into the mountains to hunt as per tradition, but they were arrested by mountain police. Consequently, community youths back home planned a protest movement. They sought alliances from other communities and kicked off the movement with the 228 Community Connected Smoke Signals Operation. In March, 2008, their 308 Hunter Operation - Marching for Our Dignity event called multi-ethnic groups to the streets. It was the largest indigenous protest event in the recent decade.

The "Smoke Signals League" was established after the march. For the past ten years, every community sets up a smoke signal on February 28 to spread awareness on community issues and appeals. The reason they chose this date is because "February 28 is the day Taiwanese society thinks about transitional justice." says Smoke Signals League member Nabu Husungan Istanda, "but for so long, the transitional justice of the indigenous peoples has been marginalized and overlooked. Therefore, on this day we lit up smoke signals to tell the ancestors that their children are still protecting the communities, and to tell society that transitional justice without justice for indigenous peoples is not the true transitional justice Taiwan seeks."

The Younger Generation Carries On:

We Still Have Work to Do

Around 2012, the indigenous peoples’ protest movements became more frequent and covered more issues. For example, the Anti-Beautiful Bay Resort in Taitung BOT Development Project, which had dragged on for many years and is constructed on the traditional land of the Pangcah, the "Dance for Sra: Protecting Dulan Cape" Taitung Anti-Dulan BOT Development Project at Dulan community, and the "Protecting our ancestral spirits: object relocation and reburial of our ancestors" movement at Katripulr Community in Taitung. Early indigenous movements were mainly fighting against oppression from the authoritarian system and protecting individual dignity; but the incidents mentioned above are actually land grabbing under the guise of land development. This shows that under the strong pressure of neo-liberalism and without actual equal autonomy to the government, the situation of the indigenous peoples is still grim.

The 2013 Anti-nuclear waste March appealing to move nuclear waste out of Orchid Island, and the "Do not say goodbye to the east coast" March, which was about environment protection, assembled communities on the east coast that were greatly afflicted by land issues to take to the streets once again. This marked another peak of unique indigenous movements: unlike past indigenous movements which were usually connected with opposing political forces, recent indigenous movements often collaborate with civic organizations and form wide-spread social movements.

At the end of 2013, Family Guardian Coalition appropriated the traditional practice of Malastapang (The Exploit-praising Ritual) of the Bunun people and used it in their march to oppose diversified family households. This angered the indigenous peoples and a group of indigenous youth who met on the street decided to openly speak out against it. Thus the Indigenous Youth Front was born. To the organization, indigenous movements are no longer a stand-off between the indigenous and Non-indigenous peoples, but an initiative of the overall value and choice of the Taiwanese society. Therefore the Indigenous Youth Front began to take part in various social issues, voicing the indigenous youth's opinions on mainstream society. They have made their presence known in events such as the 330 Sunflower Movement, the Anti-curriculum Campaign, marriage and gender equality campaigns, and Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples name rectification movements.

In addition to taking to the streets, the Indigenous Youth Front also works on empowering local youth. In 2013, the Front organized the "Indigenous Youth Consensus Camp" with the Association for Taiwan Indigenous Peoples' Policy (ATIPP) and LIMA Indigenous Youth Group. Campers can share their thoughts and experiences, discuss issues, and gain practical experience during the events. The camp aims to encourage the younger generation to be more aware of public issues and have the ability to react. The Front continues to organize Consensus Camps and support various indigenous issues everywhere, including the Bunun hunter Tama Talum case, the Kaohsiung Ljavek community anti-relocation case, and protest against excluding private-owned land in traditional spaces. Hopefully this will help the mainstream society be more aware of the rights of the indigenous peoples, and, as a result, understand and support the causes.

Indigenous movements in Taiwan have been through highs and lows, yet we have never given up. We hope to build a society where people can understand and respect each other, and everyone can co-exist with the best intentions, values and methods. Acknowledge our differences and learn to respect them. Recent indigenous movements are no longer only relevant to indigenous peoples, but are campaigns concerning all mankind's collective choice and expectations of the future.

Please note that words of“barbarians”,“uncivilized”used in this Issue only reflect to original texts used in the quoted historical literature and they do not contain any discrimination.

─ References ─

阮俊達,〈台灣原住民族運動的軌跡變遷(1983-2014)〉,臺北,國立臺灣大學社會學研究所碩士論文,2015年。

尤哈尼.依斯卡卡夫特,〈我們還有夢嗎?原住民運動的觀察與反思〉,《原運三十:回顧與前瞻》,臺北,翰蘆圖書出版有限公司,2018年。