As with many colonial regimes, various identities and names, ranging from terms such as “barbarians (番)” were adopted during the Qing rule and Japanese occupation period to “mountain compatriots” created by the Nationalist Government, were used to refer to the earliest settlers on this land. Those name tags carrying negative connotations gradually ate away at the subjectivity and culture of these residents. In the 1980s, the outcry “Who am I?” coming from the indigenous peoples in Taiwan was responded by a wave of name rectification movement mobilized by themselves.

What does the term “indigenous peoples” mean? Who are they? Since the call for the title “indigenous peoples” was issued in the 1980s, the laymen public still do not have a clear clue, as to why indigenous peoples have fought for the name change, and the background behind this movement.

The term “indigenous peoples” means, literally, people who are indigenous to the land they reside. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples further defines it as “those, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, have retained cultural, historical, political, and economic characteristics that are distinct from those of the dominant societies in which they live.” In other words, colonisation resulted in the creation of indigenous peoples. Recorded history of the past 400 years of Taiwan reflects exactly the deprivation of the status and culture of the indigenous peoples by the foreign colonists.

Turning from Main Player to the Other Typology

of Barbarians, and Mountain Compatriots

The term “indigenous peoples in Taiwan” refers to the group of peoples originally dwelling in Taiwan before the 17th century. They are part of the Austronesian-speaking peoples spreading over the Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, and Southeast Asian islands. However, extensive overseas exploration emerged throughout the 17th century, and foreign powers started to go on expeditions across oceans, continents, and archipelagos, in order to compete for resources and profits in expansion for power. As a result, Taiwan became a very crucial hub in Asia for those countries.

The Netherlands and Spain were the first two nations that sent people to Taiwan for trade, followed by Ming Jheng forces, Qing Dynasty, Japan, and the Nationalist Government as well as a huge number of Non-indigenous Chinese immigrants. After going through large-scale and systematic reforms enforced by different “nations” in the name of governing, indigenous peoples gradually lost their land, languages, culture, and even names, eventually becoming the ethnic minority in Taiwan’s society.

It was not until the Qing Dynasty had the more systematic assimilation policies been implemented. The Qing government called Taiwan’s indigenous peoples “barbarian” meaning that they were alien to the “Jhongyuan Culture (Culture of China’s Central Plains).” The word “barbarian” carries pejorative connotations such as “brutal” and “uncivilized.” They were then further classified into “uncivilized barbarians” and “civilized barbarians” according to their degrees of submission to the Qing government and acceptance of and familiarity with Jhongyuan Culture.

Uncivilized barbarians were those whose location of residence was off the national border, which means the Central Range, which was out of reach by the Qing government, whereas civilized barbarians were those who resided in the western plains area of Taiwan. They neighboured Chinese Non-indigenous people, paid taxes, and engaged in physical labour. In the 200 years of control, the Qing government focused its attention on governing civilized barbarians. To avoid Non-indigenous people and indigenous peoples conspiring with each other against the Qing government or fighting with each other, the government segregated Non-indigenous people with indigenous peoples. Due to the poorly devised strategies and Chinese immigrants from China’s southeast coast pouring in, the civilized barbarians lost a huge amount of land. For survival, indigenous peoples started to migrate or assimilate into the societies dominated by Non-indigenous people. Consequently, the subjectivity of their cultures was the first to suffer.

Toward the end of Qing rule, Japan was going through a period of modernisation, the so-called Meiji Restoration, which turned the country into one of world’s super powers. In 1895 after the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan defeated China, who ceded Taiwan to Japan. Taiwan became Japan’s first colony. After the Japanese government took over, it followed suit and adopted Qing government’s approach to treating indigenous peoples as barbarians and segregating them into wild and civilized categories. That is because it occurred to the Japanese government that the civilized barbarians were not any different than Non-indigenous people after a long time of being controlled and assimilated by the Qing government. Therefore, they became more compliant and naturalised to fit in with Japanese-rule society. The uncivilized barbarians, however, remained untamed, and got in the way of the government exploiting forest resources and land in Taiwan. Therefore, at the beginning of the Japanese rule, focus was placed on this group of people, and the colonial government devised the “Aborigines Control Programme.” They not only subjugated the untamed indigenous peoples with military forces, but also implemented educational policies to assimilate and tame them. As the Japanese military forces pushed further inland, they also gradually took over the entire island.

During the late Japanese colonial period, the situation of the Second World War made Japanese government enforce a policy of imperialisation to ensure loyalty of Taiwan’s people to the Japanese empire and a steady source of soldiers. This move to completely control “Japanese” uncivilized barbarians to make indigenous peoples adopt Japanese names, forming Takasago (highland indigenous peoples) Volunteer Armies to fight in battlefields in the South Pacific region. In addition, they changed wild and tamed savages into “highland” and “plains” indigenous peoples. This implies that all the barbarians completely became subjects of the Japanese empire.

Japan lost the Second World War, and the Nationalist Government took over Taiwan. To ensure that the state-building ideology, a.k.a. the mindset of ethnic Chinese, was followed, the Nationalist Government adopted comprehensive “de-Japanising” policies, changing the term “Takasago” to “mountain compatriots” and forcing the indigenous peoples to abandon their Japanese or original names and adopt Chinese names. The indigenous peoples became naturalised by the government.

The nationalist government reckoned that the mountain communities compared with their counterparts on the west coast were not only poor, but also so comparatively less developed. They were the ones who were the most disadvantaged group, needing assistance. Consequently, various assimilation policies that morphed the mountain peoples into plains peoples were carried out to force the mountain communities to be modernised and to move to the plains. To identify the intended policy recipients gave rise to the terms of “highland mountain compatriots” and “lowland mountain compatriots.” As for Plains Indigenous Peoples, since they were considered completely “civilised,” no particular policies were necessary, so they lost their ethnic identity, which was erased from the administrative domain.

From “Barbarians” to “Indigenous Peoples”

Indigenous Peoples Returned Collectively

Nonetheless, all these policies aimed at helping the mountain peoples adapt to the mainstream society made the indigenous peoples’ society, culture, politics, and economy collapse. In addition, they slowly lost their land area by area. To make things worse, the collapse of traditional communities and the pursuit of modernisation urged a huge number of indigenous peoples to move to cities to find employment. Their communities became slowly desolate.

Moreover, the life of the indigenous peoples migrating to cities was a bumpy road. Problems like ethnic differences, discrimination, and the gap of personal finance and education between Non-indigenous people and the indigenous peoples, etc. led the indigenous peoples living in the cities to work low-paid jobs in factories, mines, in the deep sea fishing industry, and so on. They had to take on highly risky employment, and even worse, some teenage girls were reduced to child prostitutes. Step by step, the indigenous peoples became marginalised; status and subjectivity completely disappeared under state governance. The survival of their communities were in peril as well.

Apart from struggling to make both ends meet, the indigenous peoples had always been referred to as “barbarians” or “mountain compatriots,” which indicates that the ruling governments had long considered them the alien, barbarian, impoverished, backward, and inferior “others.” With various regimes, discriminative titles took root in the society of the indigenous peoples and became a systematic approach in dividing and managing Non-indigenous people and the indigenous peoples. Also, in accordance with the levels of improvement and submission, they were separated into uncivilized /civilized and plains/Takasago indigenous peoples. The rulers made good use of this typology to make different communities oversee each other.

This hierarchy put Non-indigenous people on the high end of the spectrum and indigenous peoples on the other extreme end stigmatised and stereotyped the indigenous peoples as uncivilized, ignorant, and barbarian. Since the Japanese rule, the stereotypes had been reinforced through education system (for example, the story of Wu Fong, who was said to die at the hands of indigenous peoples, in the textbook) which confused the indigenous peoples vacillating between their inner voices and outer opinions. They had no choice but kept on asking, “Who am I?”

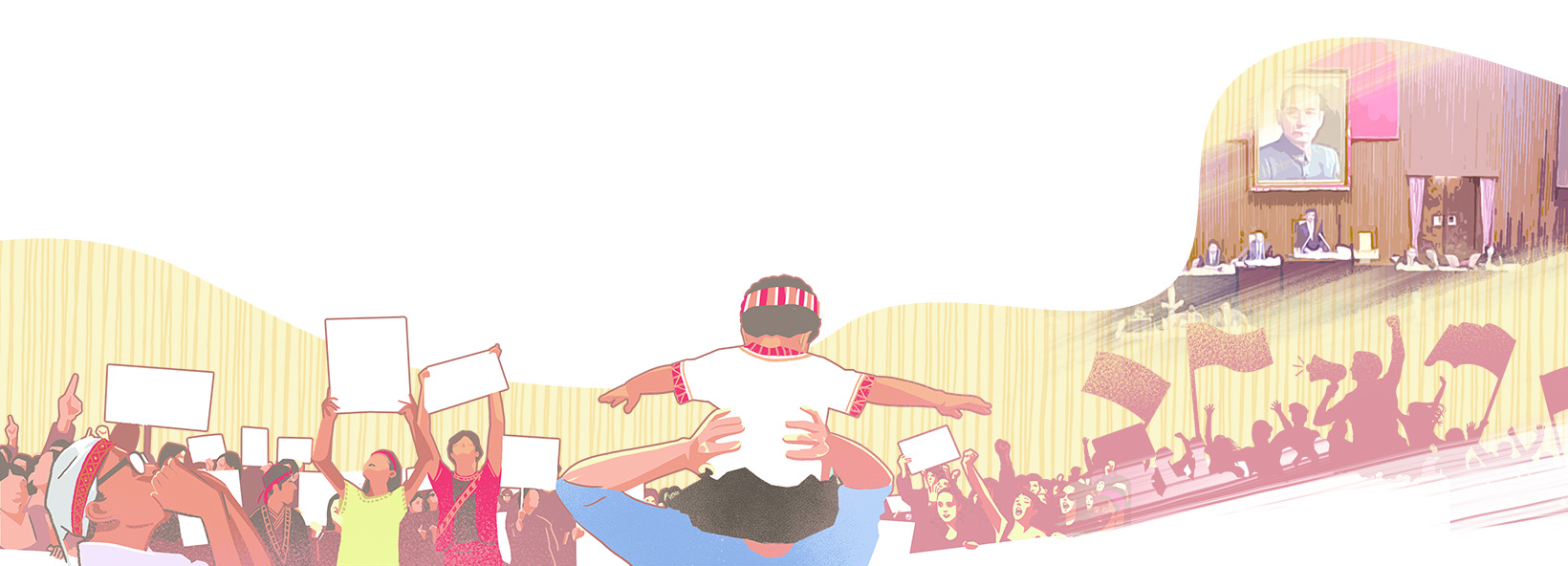

This contradiction was translated into various movements in the 1980s. At that time during the post-martial law period, Taiwan was faced with waves of democratisation and localisation movements. Many non-KMT protest movements were proceeding in top gear. Inspired by this trend, the indigenous intellectuals did not only focus their attention on sufferings inflicted on people living at the bottom of the society, but also realised that the subjectivity and inner ego of the indigenous peoples was on the brink of collapse. By sharing the same experience of being colonised in history, as well as being endowed with the origin, languages, and cultures different from the mainstream Non-indigenous people, the indigenous peoples joined hands with other circles to organise indigenous movements. This move shaped the collective identity of “Taiwan’s indigenous peoples.” They started to reclaim their lost land, identity, and autonomy, etc. through all sorts of street protests. They fought for their own rights and challenged the social structure dominated by Non-indigenous people.

Among all campaigns, the most successful ones were the ethnic identity recognition movements, urging the government to modify the laws changing “mountain compatriots” to “indigenous people” and “indigenous peoples,” restoring the traditional names of the indigenous peoples, and eliminating the typology of dividing them into highland and lowland mountain indigenous peoples. The purpose of ethnic identity recognition was nothing but to rid of the derogatory titles, and to replace the collective memory of colonisation with a whole new name that is representative of each indigenous community.

Proudly

Shout out My Name

The awareness of self-identity gave impetus for indigenous movement, which challenged the system that had long centred on ethnic differences and brought about constitutional reforms. In 1994, in the Third Amendment of the Constitution, the term “indigenous peoples” appeared instead of “mountain compatriots” in the Additional Articles 1 and 3. In the the same Amendment, a clause relevant to the indigenous peoples was added. In the same year, this Amendment was promulgated on the 1st of August, which also became Taiwan’s Indigenous Day. Subsequently in 1996, the Council of Indigenous Peoples of Executive Yuan was established marking the first central governing authority for the indigenous affairs. In 1997, Article 10 of the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution regulating the development of the indigenous peoples guaranteed their rights to the social welfare, economy, land, education, languages, and cultures.

The Amendment of the Constitution changed the way Taiwanese people referred to the indigenous people as a whole. With the same token, the status and identity of the individuals required the same rectification, i.e. their traditional names shall be restored. Thus, the Ministry of the Interior revised the “Naming Category Law” in 1995 to enable the indigenous names to be registered in the household registration documents and on the I.D. card. However, it was stipulated that their names should be transliterated with Chinese characters. The problem was that each indigenous people had their own naming logic and approach (Pangcah and Atayal, for example, adopt the patronymic naming system. Paiwan people add the household name to their name). The transliteration with Chinese characters not only forced the indigenous peoples to adopt the Chinese name format of one-character surname and two-word last name, but also refrained them from pronouncing their names accurately in their own languages. As a result, in 2003, the government revised the laws enabling the indigenous peoples to register their name transliterated with Romanization along with that with Chinese characters or the Chinese name.

Although the indigenous peoples can adopt their transliterated name with Romanization in compliance with the laws, the society does not make it easy for them to restore their traditional names. Many public and private institutions have not made adjustment to their systems and forms accordingly. The insufficient understanding of the public towards their naming cultures has caused much inconvenience in the life of those who have restored their traditional names.

The Peoples who Have No Names,

Not Yet

The indigenous peoples have obtained protection in the laws, but the existing “legitimate” indigenous peoples are those who were referred to as “barbarians/ Takasago.” Many “civilized/plains indigenous peoples” have not yet been able to restore their identity.

During the period of indigenous movement, the Plains Indigenous Peoples already appealed to the government to take their existence seriously. Thanks to the differentiated experience of colonisation in history, Plains Indigenous Peoples were considered utterly Sinicized, not in any way like indigenous peoples. They have lost their language and culture. The public often question and denounce their motives for official status recognition. It is suspected that they do so only to get subsidies of all sorts, instead of identifying themselves as part of the indigenous peoples.

The Plains Indigenous Peoples in every corner of Taiwan face hostile questioning, and have made every endeavour to re-establish their ethnic identity. Illustrations include Siraya in Tainan, Taokas in Miaoli, Pazeh in Nantou, and Kaxabu. For years, they have strived to revive the culture and language of their own people and propose changes to laws. Finally, in 2017, there was an opportunity to revise the Indigenous Peoples Status Act. In the amendment, the “Plains Indigenous Peoples” was added to the two existing “Mountain Region Indigenous Peoples / Lowland Region Indigenous Peoples” status categories.

This amendment has raised not only a glimmer of hope for recognising their official status, but also a lot of protracted controversy, such as concerns that the national budget and resources will be taken away, the typology to divide mountain / lowland region indigenous peoples still exists, and identity recognition is carried out without following the will of the indigenous peoples, etc. Moreover, the electoral politics of indigenous peoples (mountain / lowland region indigenous peoples elected as legislators and councillors) also causes irritation. All of these indicate that the issues concerning Taiwanese Indigenous Peoples are filled with political competition, and make way to problems to self-identification.

My Name;

Your Name

From identity recognition of indigenous peoples as a whole to name rectification for individuals as well as the on-going status restoration of Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Peoples, indigenous peoples strive to make their name and voice heard either on the street or in the political arena. The indigenous peoples seek survival in a tight spot and find a position in Taiwan’s society. They also push Taiwan to turn from a mono-ethnic society to one with ethnic diversity. Nevertheless, there is still a huge gap between dreams and reality. Status restoration is just the beginning. Yet, the discrimination and stigmatisation that have long existed in the society are not erased. The dialogue between the indigenous peoples and the main stream society and among different indigenous peoples should continue in any forms possible, be they education, mass media, or social movement, etc. It is hoped that through restoration of status and names, many people will get to know more about Taiwan’s indigenous peoples.

Please note that words of“barbarians”,“uncivilized”used in this Issue only reflect to original texts used in the quoted historical literature and they do not contain any discrimination.

─ Reference ─

謝世忠,《認同的汙名:臺灣原住民的族群遷徙》,臺北:玉山社出版公司,2017年。

孫大川,《夾縫中的族群建構:台灣原住民的語言、文化與政治》,臺北:聯合文學出版社股份有限公司,2010年。

詹素娟,《臺灣平埔族的身份認定與變遷(1895-1960)─以戶口制度與國勢調查的「種族」分類為中心》,臺北:《臺灣史研究》,第12卷第2期,2005年。