In March of 2020, an unexpected foreign contestant amazed the storytelling competition held by Hualien City Office for promoting indigenous languages. Speaking Sakizaya fluently, this dark horse told a vivid story of a young man’s unsuccessful quest for a girlfriend. Although it was his first time to enter the competition, he ended up with the third place, which immediately became a topic of discussion in the circle of indigenous language promoters: There is a foreigner in Hualien who can speak Sakizaya!

“One can’t say he’s been to Taiwan without getting to know its indigenous culture.” Jack Lopchi Chan, 62, is an immigrant hailing from Hong Kong and has spent decades studying and working in Canada previously. In 2009, he decided to move to Taiwan to search for a suitable environment for his daughter to learn Chinese. But having been in Taiwan for so long, it wasn’t until last year when he began learning the Sakizaya language that he began to feel a true sense of closeness to the land and its culture.

As early as when he was in Canada, Chan has grown fascinated with indigenous culture. Canada is home to more than 600 indigenous peoples, and in Victoria alone, where he resided, eight different ethnic groups live close to each other while still retaining their unique languages and cultures. However, having suffered severe oppression and discrimination from the government, Canadian indigenous communities have always distanced themselves from the outside world and now are also confronted by the threat of population outflow. Although he did make some indigenous friends as a student, due to their early exodus from the homeland, Chan never had a chance to visit their communities and get a deeper understanding of their culture.

Rising from the Ashes

a Fascinating Story of Sakizaya’s Rebirth

To provide his daughter with a good learning environment for Chinese, Chan once considered relocating to China or Hong Kong. But he ended up moving to Hualien, drawn by the tranquility and relaxed atmosphere of eastern Taiwan, which reminds him of the vast expanse of Canada’s environment.

Chan loves to play tennis in his leisure time. Therefore, he gets to make a group of indigenous friends hailing from various ethnic groups in Taiwan, including the Pangcah, the Truku, and the Bunun. Under the invitation of his Pangcah friends, Chan has the chance to visit Taiwan’s indigenous communities and attend annual traditional rituals, which helps to expand his circle of friends. In 2019, Chan made two more Sakizaya friends.

Chan loves to play tennis in his leisure time. Therefore, he gets to make a group of indigenous friends hailing from various ethnic groups in Taiwan, including the Pangcah, the Truku, and the Bunun. Under the invitation of his Pangcah friends, Chan has the chance to visit Taiwan’s indigenous communities and attend annual traditional rituals, which helps to expand his circle of friends. In 2019, Chan made two more Sakizaya friends.

The Sakizaya was officially recognized by the government as Taiwan’s 13th indigenous group in January of 2007. Currently, it has a population of less than 1,000. Though newly recognized, the Sakizaya people have been waiting for long to regain their identity. With the introduction of his Sakizaya friends, Chan came to know the tragic story of the Sakizaya: the Karewan Incident. The Sakizaya was once the largest indigenous community on the Kiray Plain (today’s Hualien City). However, in the late 19th century, they suffered a massacre in their rebellion against the Qing dynasty’s policy of opening up the mountains and pacifying indigenous peoples. The Sakizaya people came near to being exterminated. Fearing that they would be hunted down and killed, the surviving villagers hid themselves amongst their compatriots, the Amis, for 129 years. It was not until the 1990s that the Sakizaya began its fight for recognition, which was finally achieved 13 years ago. Only then could they rightfully say,“ we are Sakizaya!”

“I am captivated by the story of the Sakizaya,” says Chan, who is even more moved by their history and culture after attending the Palamal (the fire god ritual), an annual event held in memory of ancestors. Solemn and quiet, the ritual symbolizes the Sakizaya’s “death and rebirth from fire.” To add more significance to the event, the village elders will relate the stories to young descendants about the halcyon days of their ancestors’ farming and hunting life on the Kiray Plain, as well as the bitterness of displacement after the village’s extermination. The intention is to pass their history along to the next generation, hoping to get young people familiar with their roots and inspire them to glorify the Sakizaya community.

Sakizaya Made Easy

Learning with Romanization

Chan seems to have a connection with Sakizaya that knows no end. Last year, he happened to meet a Sakizaya language instructor who was impressed by his keen interest in the Sakizaya culture. So he invited Chan to attend a series of indigenous language classes at Hualien City Office. Chan was excited to find out he didn’t have to be Sakizaya to be eligible for the course, so he signed up eagerly.

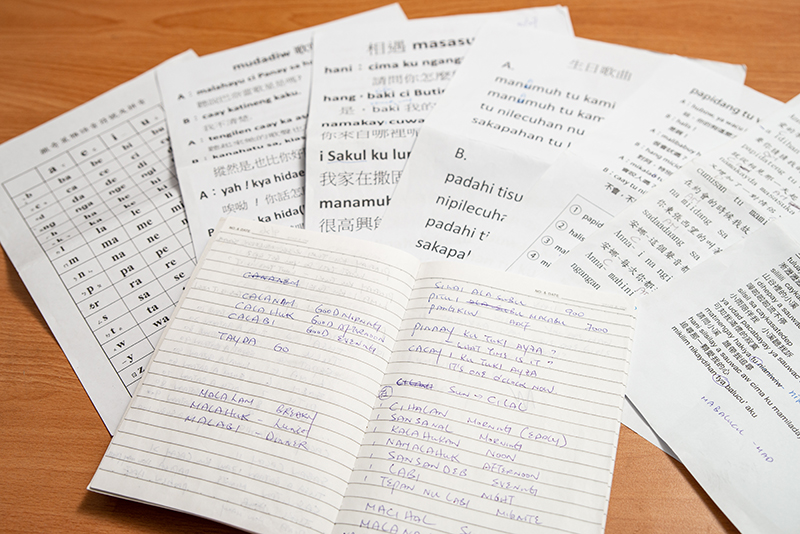

In the two-month beginners’ class, Chan learned to say basic greetings in Sakizaya. Later he went on to enroll in the storytelling class to learn more about different situations for daily dialogue. During the interview, he excitedly makes a display of his textbooks and handouts, introducing them one after another: some lessons are about songs, some for shopping and dining, all of which could be readily applied in everyday life for various purposes.

Jack Lopchi Chan (third from the right) got to know a group of Sakizaya friends in the language class. Normally they speak Sakizaya for chatting and sharing their lives.

“I’ve always emphasized the importance of practice when I teach English,” says Chan. After relocating to Hualien, he has taken on multiple titles. He was a former English lecturer at Tzu Chi University and now serves as the President of Hualien Toastmaster Club. Believing that a language that is no longer spoken is no different from dying, he strongly suggests students take opportunities to practice it in their daily lives. Now that he himself is learning Sakizaya as a beginner, he sticks to this principle by spending three or four days a week at the office for promoting Sakizaya in downtown Hualien, chatting with classmates in their native language. “The owner of the food stall near the office is also Sakizaya. I dine at the stall very often because I want to practice Sakizaya,” says Chan laughingly.

Chan also finds some shared characteristics between Sakizaya and French. Although an ancient language, Sakizaya is similar to French in terms of grammar. Syntactically, both languages feature verbs coming before the subjects, which makes him quick to learn the rope. Take “I am eating” for example. When translated into either language, the word order of the sentence is rearranged identically as “am eating + I.” Besides, some of Sakizaya’s conjunctives like “KA,” “SI,” and “SU” are also seen in French. The commonalities shared by the two different languages reinforce his interest in Sakizaya.

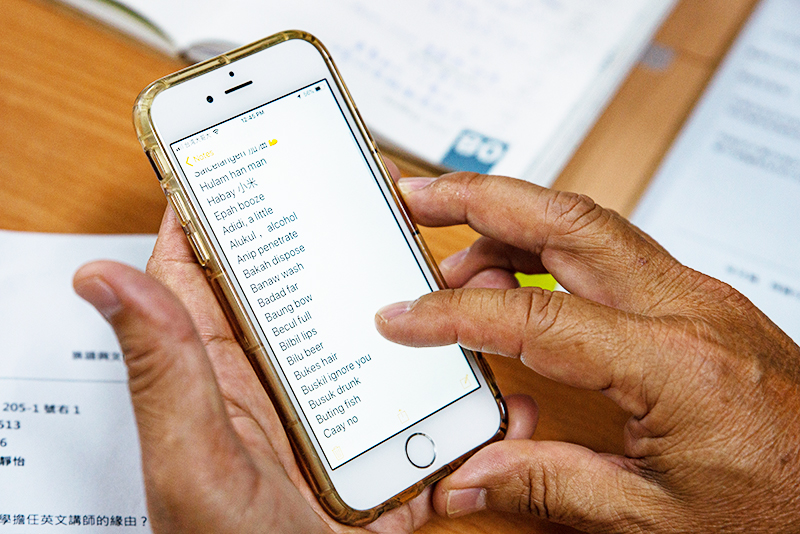

The teacher and classmates in the class are all younger than Chan. He also admits that learning a new language at the age of 60 is a bit of a challenge compared to when he was younger. But having spending decades in multilingual Canada, where most people are fluent in three to four languages, Chan keeps the motto “practice makes perfect” in mind and works hard to master Sakizaya. He expands his vocabulary through various means with the support of the smartphone and online dictionary, as well as his teacher. As time goes by, he has built a rich repertoire of vocabulary. In just one year, he has demonstrated a good command of Sakizaya by winning third place in the storytelling competition. This is not only a recognition for his hard work but also serves as a driving force that keeps him going further on the path.

A Stepping Stone

to a Foreign Culture

In addition to learning the language, Chan also travels frequently with his teacher and classmates to Sakizaya communities for such activities as visiting the monument to the Karewan Incident, volunteering for blessing ceremonies, and dining with the elders. In his view, each scene and each object he sees in the communities, compared with a superficial view seen through a quick trip, are the embodiment of Sakizaya culture that money can’t buy.

Chan says frankly that having been brought up in the Western culture, upon his first contact with indigenous culture, he is inevitably struck by a culture shock. But the most important thing is to stay respectful and tolerant, abandon the Western perspective, and put yourself in the shoes of locals instead. Only by so doing can you truly understand and appreciate the long and splendid history of indigenous peoples’ cultures.

Chan remains highly motivated toward learning Sakizaya all the time. Whenever encountering a word that he doesn’t understand, he’d keep it down on the smartphone and consult the dictionary later. Especially impressive are his handouts filled with notes he’s taken in lectures.

“Language is the backbone of all cultures. It will be hard to explore an ethnic group in depth if you don’t’ understand its language.” Chan has never stopped his pursuit of a better command of Sakizaya. He excitedly shares with us the course information for Sakizaya certification in the coming fall semester. Nevertheless, his ultimate goal is not to pass the test, but to bring himself closer to the Sakizaya through the process of learning the language.

“Currently only 400 to 500 people in the world speak Sakizaya. Don’t you think that’s cool?” Chan says with a smile. He adds that having been here for nine years, he never expected to be able to learn a new language and get to know so many friends at an early old age. If he has the time and energy, next he would like to learn about the culture of the Kavalan, the people who fought shoulder to shoulder with the Sakizaya in history. Coming into contact with indigenous peoples is like opening a window on a new world, which enables Chan to cross the ethnic boundaries and enjoy the baptism of indigenous culture.