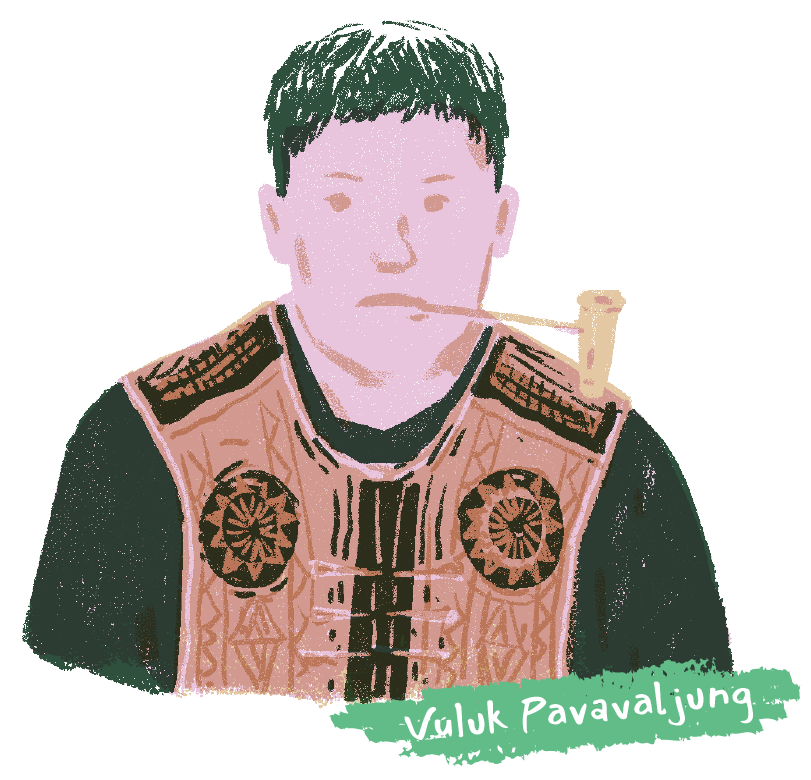

Paiwan youth Vuluk Pavavaljung from Pingtung County’s Shandimen Township has always been interested in insects, and eventually chose to study entomology in university. Combining his professional knowledge with the experience of living in his indigenous village, Vuluk shares his observations on community flora and fauna on his Facebook fanpage “The Indigenous Biology Log”.

This August, he posted an article sharing a list of 39 betrothal gifts given at his sister’s wedding. In addition to garments for the bride and groom, feathers, and clay pots, the groom also had to prepare betel nuts, bananas, taros, and sugar canes. These farm produce symbolize that the family will work diligently in the fields and have plenty of offspring. Furthermore, a pig slaughtering ceremony was held the day before the wedding, and the animal was divided into different portions: neck, legs, ribs, and organs. The documentary-like content ignited much discussion among readers, and “The Indigenous Biology Log”, which has only gone online for less than a month, was shared by over 130 visitors within a couple of days.

“Actually, all I wanted to say was look how much trouble we have to go through in a Paiwan wedding. I didn’t realize it would become such a hit!” Explained Vuluk Pavavaljung, owner and writer of “The Indigenous Biology Log”. The 23-year-old just wanted to share his own observations on his elder sister’s wedding. He didn’t expect the post to garner so much attention.

The Rich Ecology in Shandimen

Fosters a Young Insect Fan

Dewen Mountain in Shandimen Township is a treasure trove in the eyes of insect lovers. The rich and diverse ecology is home to many beetles and butterflies, which is why Vuluk, who was raised here, grew up with such a special interest in insects. After he collected the insects with his village playmates, Vuluk read up information in the encyclopedia and educated himself through other resources to make sure his insects can thrive.

“I had my own little fridge where I raised a dozen of bugs in. I kept the temperature at 25°C.” Vuluk knows every insect he kept like the back of his hand. Under his diligent care, his stag beetles could live up to one and a half year-old. And he still remembers the time he raised dragonfly nymphs in a fish tank. One late afternoon when he came back from school, he found that the nymphs had emerged as adult dragonflies. This miracle of life greatly impressed him.

Because of his love for insects, Vuluk chose to study entomology in university. Memorizing the names of different insect body parts was a walk in the park for Vuluk, and he enjoyed learning about the meanings behind insect behaviors. For example, when he saw butterflies flying about the village when he was a boy, he just though they were very pretty. But now he understands that the butterflies could be guarding their territory or seeking a mate. Every time he talks about the world of insects, Vuluk’s eyes shine with excitement. “I'm very glad I could learn all of this at school, it helps me understand the world of insects better.”

Documenting Community Wildlife

and Carrying on Cultural Customs

The title of “The Indigenous Biology Log” includes the Chinese characters for “indigenous” and “biology”, and the content is mainly about Vuluk’s experience of living in an indigenous community and anecdotes related to insects. His posts are unique since Vuluk introduces the flora and fauna in indigenous culture from a biology perspective.

This year, Vuluk’s sister got married. Intrigued by the 39 betrothal gifts on the list, Vuluk asked the elders about the meaning and usage of the items, and shared his discoveries on his fanpage. “After setting up the fanpage, I realized that a lot of people actually care about indigenous affairs and the village ecology.” Vuluk said happily.

His sister’s wedding gave biology lover Vuluk more opportunities to learn about and introduce plants that often appear in indigenous daily life and common rituals. For example, the wreath headdress “Lakarau”, which is often used in community rituals, is mostly made with the stems and leaves of pigmy sword ferns then decorated with marigolds. The story behind this is that marigold seeds go where the wind takes them and can blossom anywhere they land. This symbolizes that the strength of Paiwan women and that they can carry and support her family through thick and thin. When the community members were making the wreaths, Vuluk saw a type of fern he had never seen before, and shared a photo of it on social media. An older brother in the community replied that it is limpleaf fern, also known as “lamlam” in the native language. Such interactions with the community bring new knowledge to both the readers and the author Vuluk.

His sister’s wedding gave biology lover Vuluk more opportunities to learn about and introduce plants that often appear in indigenous daily life and common rituals. For example, the wreath headdress “Lakarau”, which is often used in community rituals, is mostly made with the stems and leaves of pigmy sword ferns then decorated with marigolds. The story behind this is that marigold seeds go where the wind takes them and can blossom anywhere they land. This symbolizes that the strength of Paiwan women and that they can carry and support her family through thick and thin. When the community members were making the wreaths, Vuluk saw a type of fern he had never seen before, and shared a photo of it on social media. An older brother in the community replied that it is limpleaf fern, also known as “lamlam” in the native language. Such interactions with the community bring new knowledge to both the readers and the author Vuluk.

“I steer away from common indigenous plants such as millet, may chang, and red quinoa.” Vuluk enjoys researching the meaning and symbolism behind the plants in indigenous culture, because the traditional indigenous lifestyle is closely connected to the natural resources in the environment. The diverse use of plants in medicine, cooking and other aspects of life is part of the wisdom of living passed down from generation to generation in indigenous communities. Vuluk mentioned tropical crepe myrtle, the plant he is researching recently, as an example. This kind of myrtle is the “firewood of love” in Paiwan culture. In the past, unmarried young men would leave a bundle of tropical crepe myrtle firewood at the doorstep of the girl he fancies. “We used this plant to get the girl!” Concluded Vuluk with a laugh.

Caring about the Balance between Ecology and Culture

from a New Generation's Perspective

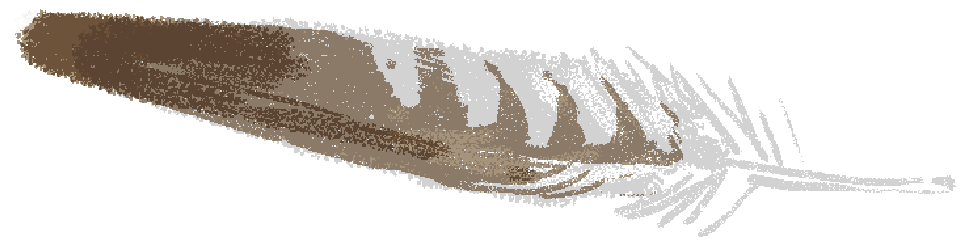

In addition to finding wisdom in the surrounding ecology, Vuluk also closely observes traditional indigenous culture transformations in modern society. He brought up an article published by the NPUST Bird Ecology Lab which mentioned that the Paiwan and Rukai people now are promoting the use of realistic synthetic feathers instead of real ones so that the Hodgson’s Hawk-Eagle, or “adis”, will not go extinct. This hawk-eagle is listed as a level-one protected species, and there are less than 500 pairs of them left in Taiwan. However, Vuluk was puzzled by the information: where is the market demand for these feathers?

Looking for answers, Vuluk studied academic papers and went back home to ask community elders. That’s when he learned that according to their legends, the hundred-pacer snake, which is the ancestor of the Paiwan people, transforms into a male Hodgson’s Hawk-Eagle in old age. Thus the hunting of male Hodgson’s Hawk-Eagles is forbidden as the bird is a form of their ancestor. If someone accidentally kills one, the feathers must be given to village royalty. Members of the royal family will wear the feathers during important events, such as weddings, as a symbol of nobility. However, nowadays different society classes frequently intermarry and wearing feathers is no longer the exclusive right of the royal family; consequently, the demand for the feathers have significantly increased, bumping up the price for them as well. Vuluk explained that when the client orders feathers from the hunter, prices vary for different parts of the feather, the minimum is around NTD ten-thousand dollars, with some going as high as over fifty-thousand.

“As a young man of the Paiwan community and someone who studies biology, I fully support the project to use synthetic feathers. I hope we can promote the project to other communities.” Vuluk acknowledged that it is no longer suitable for people to hunt the protected species for their feathers, and synthetic ones can help the people reach a balance between traditional culture and ecological preservation.

Daily Life in the Community

are Material for Inspiration

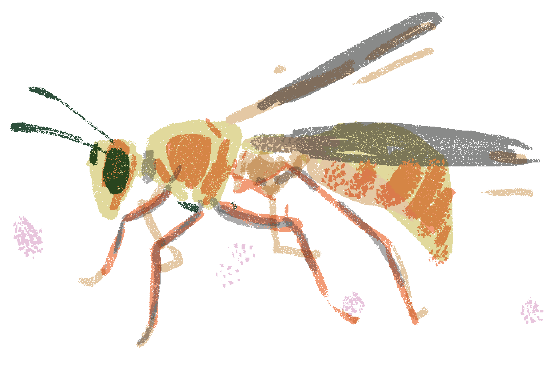

Vuluk returns to the village about once every month to look for writing inspiration and material. He once removed a bee hive at his house and observed the emergence of paper wasp drones; and during a typhoon day, he accidently found a yellow-margined box turtle (a level-two protected species) at his door. For Vuluk, inspiration comes from everywhere in community life.

Though the indigenous village offers countless inspiration, available information regarding these plants and animals are still limited, and not much can be found on the internet. Vuluk has to spend up to a week reading papers and compiling information before he can churn out an effortless, seemingly spontaneous article for his Facebook post. And there is no profit from operating the community, but Vuluk says doesn't mind. “This is what I enjoy doing. Even if it is not a popular topic, I will still keep on doing it.”

“When I lived in the community, I always took traditional culture for granted. But a lot of people have no access to these things.” After he moved to the city, Vuluk realized that a lot of indigenous people who grew up in the city are interested in the world of traditional culture yet have no means of accessing it. This further encouraged him to record his daily life observations, combine them with his own professional knowledge and share them online so that everyone can have the opportunity to learn about the traditional culture and ecology.

Piece by piece, the project grew. Now the online ecology log not only contains segments of Vuluk’s daily life, but also documents precious traditional indigenous culture and ecology from a different perspective.