In modern society, clothing is manufactured in factories by machines. People only care about whether the garment is pretty or fashionable; yet if the threads carry no emotions or stories, the clothes are but a decorative shell. In a traditional Atayal society, skillful Weavers require a long time to train and cultivate. Weaving refines a girl's character and skills and consequently shapes the people's culture and identity towards the family. From planting the ramie to weaving the cloth, the Weavers preserved time and culture in every bolt of cloth and every piece of garment they made.

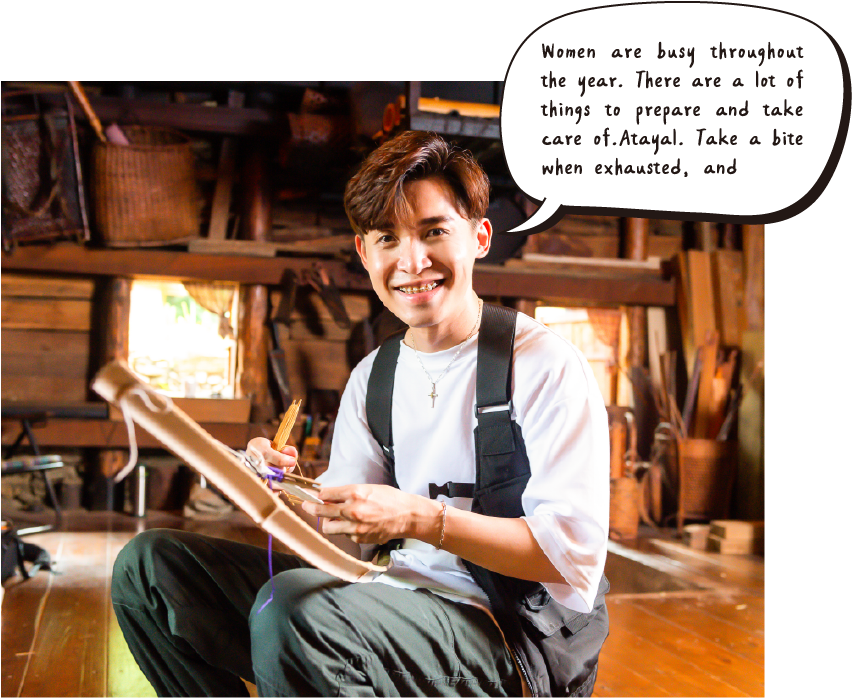

Pisuy, who grew up in the city, chose to relearn the core spirit of Atayal weaving. She began to promote the cultural revitalization of Atayal weaving. Experiencing the wisdom of the ancestors with her hands, Pisuy is gradually learning more about this land.

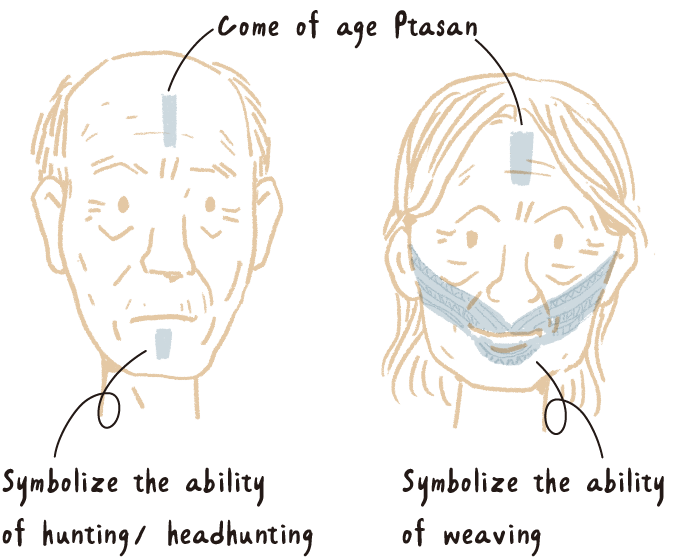

The Ptasan is an important mark and pattern among the Atayal people. When a child comes of age, they will get Ptasan art on their foreheads. But what about the other Ptasan markings?

According to Atayal traditions, the men hunt and the women weave. If a person wishes to have more Ptasan on their face, they must have very good skills (hunting skills for a man and weaving skills for a woman). If you don't have any Ptasan on your face, you will have trouble finding a spouse!

Simply put, a man's hunting skills indicate their ability to survive and provide. He should be able to bring back game meat, protect his home, and support his family. It's similar to the way nowadays we would ask if a potential suitor has a car and/or house. Likewise, if a woman does not know how to weave, then the family will have no clothes to wear and no blankets to use at night.

Simply put, a man's hunting skills indicate their ability to survive and provide. He should be able to bring back game meat, protect his home, and support his family. It's similar to the way nowadays we would ask if a potential suitor has a car and/or house. Likewise, if a woman does not know how to weave, then the family will have no clothes to wear and no blankets to use at night.

In Atayal beliefs, the heaven, earth, people, and spirits are one.✱2 When you die, everyone has to walk across the Hongu utux✱1 ("rainbow bridge") and your loved ones and the ones you miss will be waiting at the other end; but if you don't have Ptasan on your face, you will not be able to cross that bridge. Thus the Ptasan markings not only symbolize the person's personal skills and ability to support a family, but more importantly, it is a connection between the person and the Spirit.

✱1: "Hongu" refers to "connect"; "Utux" refers to "soul."

✱2: For example, dreams is a regular topic in Atayal daily conversations. We consider dreams a normal means to exchange information, so talking about dreams is quite common and we listen attentively when people talk about their dreams. The Atayal do not have a very clear distinction between reality and dreams.

✱2: For example, dreams is a regular topic in Atayal daily conversations. We consider dreams a normal means to exchange information, so talking about dreams is quite common and we listen attentively when people talk about their dreams. The Atayal do not have a very clear distinction between reality and dreams.

Weaving is considered the "holistic education" for Atayal women. If a girl did not learn how to weave properly, her social status after becoming an adult or after marriage would be inferior. Mothers-in-law do not teach their daughters-in-law how to weave - they may even ask the daughter-in-law to leave when they are teaching their own daughters how to weave.

Some people would think "why wouldn't the mother-in-law help her?", but the Atayal believe mothers should teach their own daughters properly. Each girl has their own mother to teach them how to weave. However, according to Gaga✱3, if the girl lost her mother at a very young age or the mother is not Atayal, the girl can go find a mentor. She has to pay her mentor in some way, such as killing a chicken, and see if the older woman is willing to mentor her. Nowadays, if we wish to seek mentorship, it mainly depends on whether the teacher is willing to teach us and then you pay a tuition fee.

Some people would think "why wouldn't the mother-in-law help her?", but the Atayal believe mothers should teach their own daughters properly. Each girl has their own mother to teach them how to weave. However, according to Gaga✱3, if the girl lost her mother at a very young age or the mother is not Atayal, the girl can go find a mentor. She has to pay her mentor in some way, such as killing a chicken, and see if the older woman is willing to mentor her. Nowadays, if we wish to seek mentorship, it mainly depends on whether the teacher is willing to teach us and then you pay a tuition fee.

✱3 : The ancestral teachings and collective guidelines of the Atayal.

The Atayal's weaving culture was significantly impacted after Taiwan was colonized by the Japanese. Japanese anthropologists observed that when the Atayal weave, it is not simply about individual honor (that they want to create a good piece of cloth): when a group of women is weaving together for their families, the entire clan is united and thus makes them stronger. Therefore the Japanese colonial government started to oppress the activity and discouraged weaving by saying "those who weave and not work are lazy people". This changed the lifestyle of Atayal women. The Japanese even sent the best Weavers in the communities to train at silkworm cultivation stations or taught them to use handlooms and abandon their traditional weaving tools.

In the past, if you hear the thumping sounds of weaving in a house, it indicated this is a hardworking family. But if the Japanese caught you weaving, they would confiscate the tools. So in order to keep on weaving, our ancestors put millet husks into the qongu (weaving box) to muff the sounds or carried the weaving box to the work sheds in the mountains. If you see old weaving tools now, you should feel grateful because our ancestors took great care to preserve them.

In the past, if you hear the thumping sounds of weaving in a house, it indicated this is a hardworking family. But if the Japanese caught you weaving, they would confiscate the tools. So in order to keep on weaving, our ancestors put millet husks into the qongu (weaving box) to muff the sounds or carried the weaving box to the work sheds in the mountains. If you see old weaving tools now, you should feel grateful because our ancestors took great care to preserve them.

There are three types of ramie used by the Atayal in the Nan'ao region: Kgi Lapay (women's ramie), Kgi Kiway (men's ramie), and Kgi Kahat (Non-indigenous people's ramie). There are also Kgi Yungay (monkey's ramie) and Kgi Lutux (devil's ramie) which can be found everywhere along the road. However, these species of ramie are not for human use, so be careful when you are collecting the plants. Ramie is grown in the spring and harvested approximately three to four months later. It can be harvested three times a year. Elders often say that we shouldn't count the days until the ramie are ready for harvest.; rather, we should go chat with the ramie and observe their growth.

Not only is ramie used when women weave, but men would also use men's ramie to weave hunting tools. Kgi Kiway ramie is more resilient than Kgi Lapay ramie and is suitable for making net bags to carry meat on their backs. Unfortunately, the plants are no longer planted in Nan'ao. They only exist in the memories of the elders now.

Not only is ramie used when women weave, but men would also use men's ramie to weave hunting tools. Kgi Kiway ramie is more resilient than Kgi Lapay ramie and is suitable for making net bags to carry meat on their backs. Unfortunately, the plants are no longer planted in Nan'ao. They only exist in the memories of the elders now.

Just like men have to spend months preparing the wood before making a fire or going out to hunt, women also have to do preparations before weaving. It begins when they get ready to plant the ramie: how many people are there in this household? What type of clothes will she make for the annual ritual? How many quilts will the family need for winter? With a full understanding of the relationship between the skies and earth, a highly-skilled Weaver can carefully calculate how many bolts of cloth are needed for the family and knows exactly how to spin the yarn and create perfect textiles.

Traditional Atayal weaving uses a shuttle to weave the warp and weft threads together. In fact, almost all indigenous peoples in Taiwan use shuttle weaving. The Atayal weaving box is called qongu✱4 and the threading and winding tools are called Ikus. Local wood is used to make the qongus and the indigenous peoples in the Nan'ao region usually use Red Nanmu or Oldham Spicebush.

Although many documents state that men cannot touch a woman's weaving tools, the tools are actually all made by men. For example, a father would make one for his daughter, or a husband for a wife. If she figures the tool needs tweaking, the woman will also ask for a man's help. Therefore only men that are not family are forbidden to touch a woman's weaving tools. It is the same with a man's hunting knife: the husband may ask his wife to carry it for him, but women cannot touch the mgaya knife ("head-cutting" knife).

✱4 : You can identify which regional group the Weaver is from by looking at the shape of her qongu. For example, qongus from the Nan'ao region are more curvy and rounded. t should be noted that the qongu is a very personal and private tool and is often covered with a piece of cloth. The Weavers that Pisuy has met so far usually have two qongus: one for her personal weaving and the other which can be seen by others.

The patterns on Atayal cloths usually come from the maternal side of the family, some are imitated or created by the Weaver. Gradually, the patterns form distinctive characteristics that belong to a certain region. The word "roziq" in the Atayal language means "eye", yet the ancestors also used the same word to indicate the rhombus shape. Thus some people misinterpret the rhombus-shaped patterns as the "eye of the ancestors". Just to be clear, these patterns are simply patterns, the Atayal people did not give them special meanings.