Most people think of those who live deep in the mountains and sing Pasibutbut when they think of the Bunun people, but the Bunun didn’t start as mountain people, they actually originated from Lamungan, downstream of Zhuoshui River (currently where the Nantou Service Station sits). Legend has it that a great flood forced Bunun ancestors to migrate higher up the Central Mountain Range and the Yushan Mountain Range, thus dispersing the 5 main communities* in between the rivers along the mountain ranges. Later, due to growth in population, they continued to migrate toward the Laklak River basin in Dafeng, Hualien, east of the Central Mountain Range (and further onto Yuli and Cepo’), before turning south toward the three branches of the Beinan River in Taitung (XinwuL? River, Luliao River, Luye River). In mid 19th century, one of the migrating groups settled in Taoyuan District, Kaohsiung, and the group that migrated furthest south reached Laipunuk’, mid-upper stream of Luye River, and that group was the family of dssitalam, the second eldest in the Istanda (surname Hu) clan of isbukun Community. Since then, the Bunun resided in Laipunuk’ for almost half a century before things began to change when the Japanese arrived in Taiwan.

*Take todo (Todo Community), take bakha (Bakha Community), take vatan (Vatan Community), take banuad (Banuad Community), isbukun (Isbukun Community)

Halfway into its colonization in Taiwan, with the majority of indigenous peoples already conquered and the demand for forestry resources from Taiwan increasing, it became ever more urgent for Japan to control the indigenous peoples yet to surrender. The Japanese colonial government placed security and high voltage electricity in the mountains surrounding the Bunun, and stationed police posts along the security path for surveillance and communication purposes. The Mamahav settlement we know nowadays was exactly where the Qingshui Police Post use to locate, at the entrance to the Laipunuk’ area.

The standoff between the Bunun people and the Japanese government lasted over a decade. When the Wushe Incident broke out in 1930, the Japanese colonial government implemented the group relocation policy the following year and forced indigenous communities out of the mountains. That was when the Bunun people left the Laipunuk’ area, where they have resided for generations. Moving from a higher altitude to a lower altitude environment led to problems in adapting, and people became ill. One of the community members, Haisul, even lost two children due to this relocation. In 1941, Haisul decided to go headhunting and return to Laipunuk’. He attacked the various police posts along the security path by night and cut off bridges necessary for connection and communication to prevent pursuing forces, but eventually, he was lured out by his own people and got arrested. This was known as the “Laipunuk’ Incident”. After this, the Japanese colonial government demanded the mountains to be fully evacuated, burning down family houses, millet storage, and farmlands, and relocating everyone away from the mountains.

When the Japanese left in 1945, the mountains were controlled due to White Terror during the martial law period. Hence, despite the change in regime, the Bunun people still couldn’t return home. In 2000, with indigenous movements on the rise, the history of indigenous peoples gradually gained attention, and Bunun tu Asang, the Bunun Cultural and Educational Foundation, reconstructed the history of the “Laipunuk’ incident” via interviews. Two years later, they initiated the “Return Home Program”, taking the elder ones home for the first time since 1942. “I never thought I’d ever return home again in my life,” many elder ones who took part in the program shed tears.

Nowadays, Itu Mamahav tu?Pasnanavan’ is pushing for more programs to take place in the mountain, hoping to rebuild the relationship between man and the land, explore the connection between man and the indigenous peoples, and regain the ability to be man.

Having heard from Katu about the migration history of the Bunun over the century, and hiking along a part of the path leading back to the old settlement, we can really feel how each step represents the history of Taiwan as traveled by the ancestors.

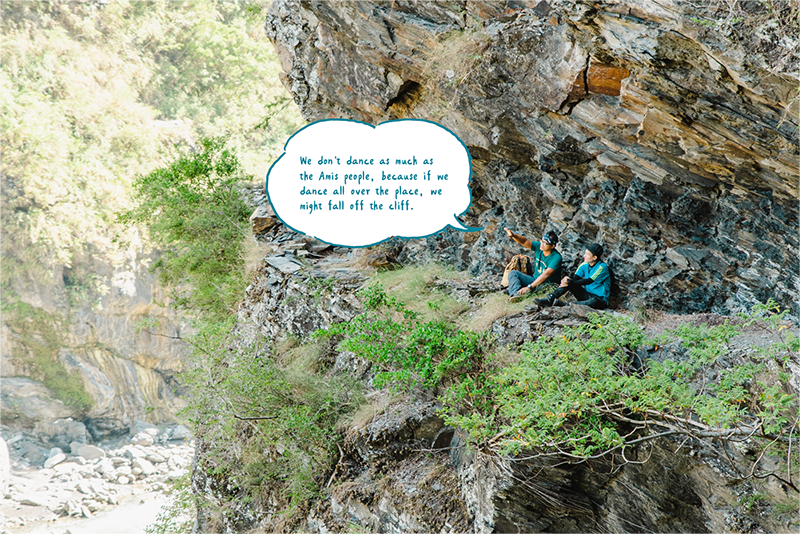

The ancient trail we are on now is the security path built during the Japanese colonial period. The reason the entrance to the mountain is fenced off is because of the most abundant and widely distributed wild Taitung cycas in the area. To protect these valuable and rare plants, a nature reserve is set up, and an application is required to enter.

Along the way, we see the remains of a family house. The owner of this house was a security guard during the Japanese colonial period and made a living working at the Qingshui Police Post, therefore no space was set aside for farmland around the family house. This family house has stone slabs stacked in a Herringbone pattern, rotating at a 45-degree angle vertically. It provides a stronger frictional force and better stability, whereas if stacked horizontally, the stone slabs would slip easily. The family house layout is a typical U-shape in reverse. There are no stone slabs with holes drilled found on the floor, therefore we assume that the door was built with a wooden frame and grass and the roof was stacked sogon grass, which explains why only the wall structure remained.

Squirrels like to hide seeds in between stone slabs and boars tend to smash against the stone slab walls in order to get to the seeds, which would cause the walls to protrude. But it could also be due to the outgrown roots.

To block the connecting path for the Japanese police, Haisul, the main person responsible for the Laipunuk’ Incident, cut off the wire cable suspension bridge connecting the two mountains. The cement bridge piers stand to this day.

Setting forth industrialization in Eastern Taiwan during its later colonial period, Japan selected two locations to build hydroelectricity plants (known as Project Qingshui), and one of which was Luye River. The narrowest point of the river bed is the most appropriate location to build a dam, and the officers built houses for engineers stationed there. However, as the Pacific War soon broke out afterward, all hydraulic engineering ceased, leaving only the remains of the cement foundation, the reservoir, and the flag pole base.

The Bunun people are used to environments with steep slopes and relatively small patches of flat land, which provide smaller areas to live in. Therefore, the social structure of the Bunun is based on families and rarely do they come in large communities. Unlike other indigenous peoples that tend to mark their territory with the community as a unit, the Bunun is all about the clan.